Editor’s Note: Sawtooth Mountaineering was Boise’s first climbing shop. It was founded by Lou and Frank Florence. The shop was an important link between many of Idaho’s premier climbers and the development of Idaho’s technical climbing scene. Bob Boyles (quoted on Page 23 of the book) noted the shop’s importance as a hub for local climbers, stating “The thirty or so most dedicated climbers in the Boise Valley often hung out at Sawtooth Mountaineering to share stories . . ..” This group of climbers, centered on the shop, are credited with some of the most challenging first ascents in Idaho. In this article, Frank recounts his and the shop’s history.

I grew up on Long Island (New York), hardly a mountainous setting. My early camping and hiking trips were in the Appalachian and Adirondack Mountains and I was introduced to mountaineering in 1970 as a student in NOLS. I stayed on with NOLS, eventually working as a course instructor in Wyoming and Washington State.

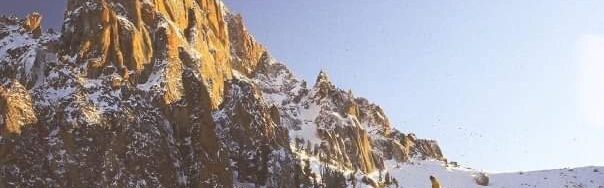

In 1972, I joined my father, Lou Florence, in bringing a small outdoor recreation equipment store to Boise. Our business (Sawtooth Mountaineering) promoted climbing, hiking, and cross-country skiing across Southern Idaho, from Slick Rock to the Lost River Range. We offered introductory climbing classes and fostered enthusiasm for climbing by hosting a speaker series with some of the leading climbers and alpinists of the day, including Royal Robbins, Henry Barber, Doug Scott, Bill March, and Sawtooth pioneer Louis Stur.

British Mountaineer Doug Scott lectured twice at our shop. The first time was in 1975. Scott came to Boise to give a talk about his recent ascent of the Southwest Face of Everest. He wanted to get in some climbing while in town and a posse quickly assembled. We went out to the Black Cliffs for what turned out to be a toasty day. Scott asked what had been done and what hadn’t and then led through a couple of each.

Scott came through Boise again in 1977 to give a slide show at the shop after his epic descent off The Ogre. And again I and a few others got a chance to climb with a famous alpinist. That time we returned to the Cliffs and he led what is now called the Doug Scott Route. Nice route, too. I remember Scott stopped at one point after trying a move and then pondered it a bit before he led through the sequence. When he came down, I asked him what he thought about it, especially that one section. “It’s all there,” he replied. “Just a lack of balls.”

Through Sawtooth Mountaineering, we conducted popular introductory clinics in cross-country skiing and helped develop an early network of ski trails around Idaho City. Long-time staff members Ray York and Gary Smith, as well as Lou and I, trained and volunteered with Idaho Mountain Search and Rescue. Days off were spent exploring the many crags local to Boise: Stack Rock, Slick Rock, Table Rock, Rocky Canyon, Morse Mountain and the Black Cliffs.

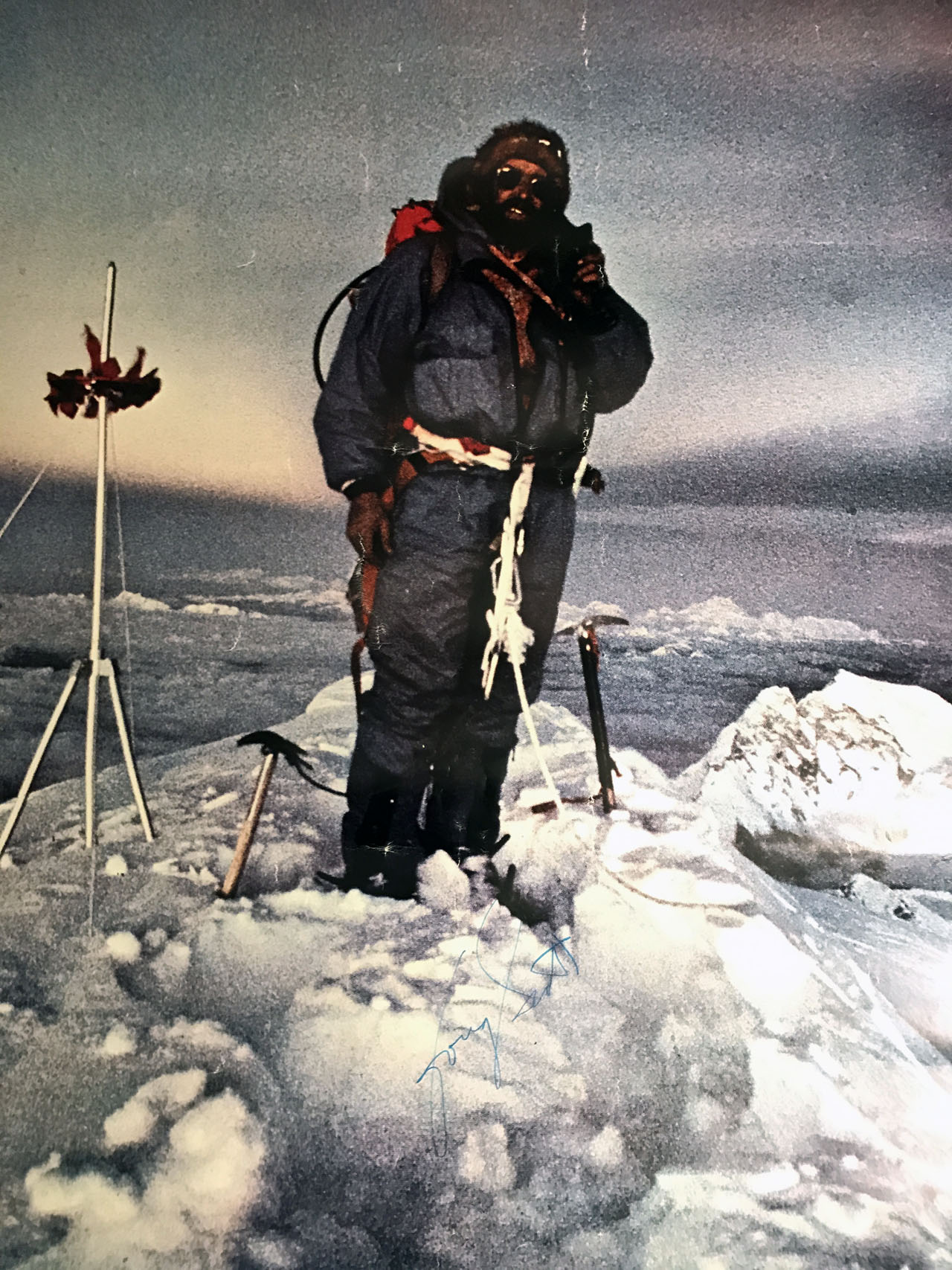

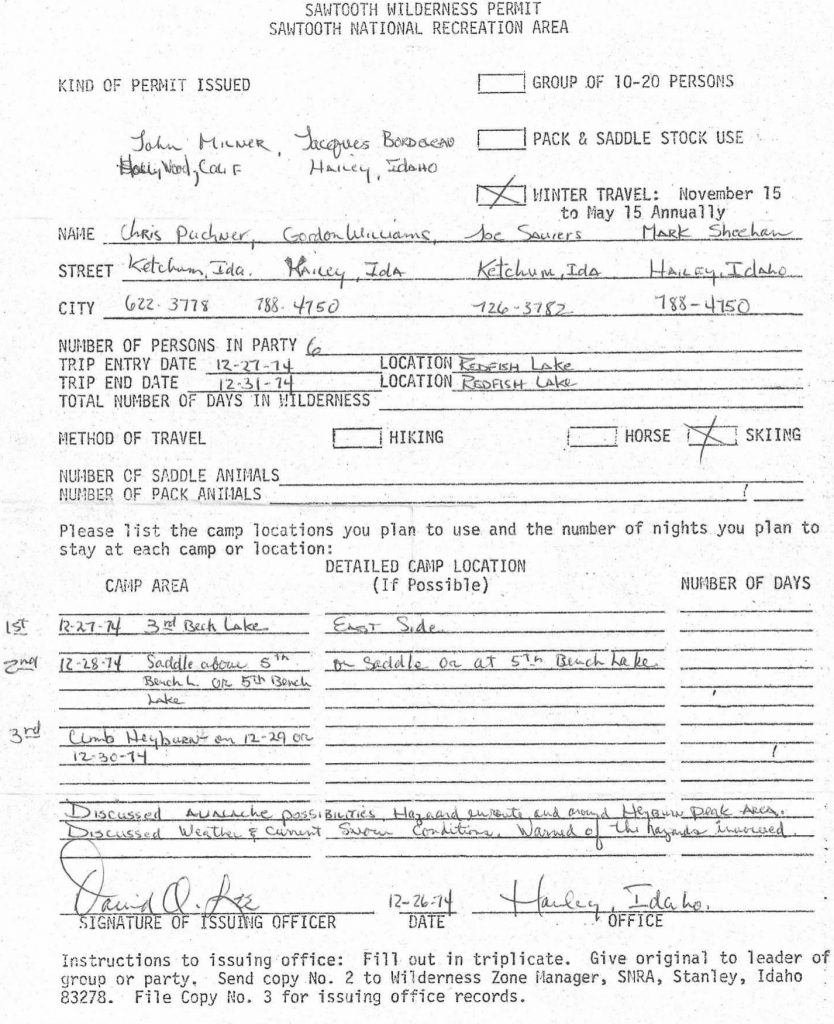

I frequently partnered with Bob Boyles and Mike Weber on technical climbs, but in the mid 1970s, there was a free-wheeling mix of local climbers who swapped leads including Tom McLeod, John Platt, Art Troutner and Charley Crist. It was a time of discovery as there was little in the way of guide books and, championing clean climbing ethics, we clanged our way up the cliffs using hexes and stoppers. We became better climbers as we challenged one another on new routes locally and expanded our alpine skills into the Sawooths and Lost River Range. In the Winter of 1974, John Platt, Jerry Osborn, Walt Smith, and I skied across the White Cloud Mountains from Obsidan to Robinson Bar. In 1976, I summitted Denali with friends from Seattle and the following year made the first Winter ascent of Mount Borah’s North Face with Art Troutner, Mike Weber and Bob Boyles.

Sawtooth Mountaineering closed in 1980 and I returned to college and a career in geology. That took me out of Boise but, from time to time over the years, it’s been my pleasure to renew my acquaintance with the Sawtooths and the Lost River Range and those same partners from back in the day.