I first saw the North Face of Mount Borah in the Summer of 1972 while working under contract with the U.S. Forest Service. We were flying helicopters near Horseheaven Pass in the Upper Pahsimeroi Valley, where our daily flights offered unrivaled views of the north and east sides of the Lost River Range. But one face in particular stood out from all the others, and that was the North Face of Mount Borah. Lacking any snow, the face was a dark, steely gray color unlike anything I’d seen in Idaho before. I wasn’t a climber at the time but that was soon to change. I never forgot what I had seen that Summer.

Two years later (1974), we made a reconnaissance hike into the cirque below the East Face of Mount Borah with the intent to find a climbing route that would lead to the summit. The lower part of the face held what looked like a large snowfield, but upon closer inspection, we found that it was more than just frozen snow. Underneath the snow was hard ice, the kind that only forms from years of accumulation, where the constant pressure slowly squeezes all of the air out of the ice, leaving it vivid blue in color. To a climber, this find was important because ice climbing generally requires specialized gear that one may not carry if expecting to only climb on snow. To the best of my knowledge, no study was ever made of this ice field before it disappeared.

A year or two later, while attending Boise State University, I heard about Bruce Otto’s discovery of Idaho’s only known glacier on the North Side of Mount Borah. Bruce was a climber and Boise State University geology student who was familiar with Mount Borah and its perennial snowfields. In 1974, while doing research for a class project, he hiked into Borah’s North Face Cirque to study the snowfield and see how much it resembled an actual glacier. What he found in ice was much more than he expected. So the next year he returned with Monte Wilson, his professor and a specialist in the study of glaciers. They would return many times over the next ten years to study the glacier and its annual changes. Bruce’s description of the glacier talks about how it was over 200-feet thick, 1,000-feet wide and 1,200-feet long. He also describes how they determined the glacier was estimated to be 500 or even a few thousand years old. For a relatively short period of time, the glacier was known as the “Otto Glacier.”

Beginning in 1973, my climbing partners and I embarked on an ice climbing binge, seeking ice wherever we could find it. We found a fair amount of seasonal, winter ice in the canyons of Southern Idaho, but rarely found the hard alpine ice we were craving. The Sawtooths were too low in elevation, and while the nearby Tetons were the most likely place to find alpine ice, we found the range’s ice seasonal and unreliable. While volcanos like Mounts Hood and Rainier had glacial ice, climbing into open-ended crevasses, just to practice, didn’t seem worth the effort for the risk. The Canadian Rockies did have what we were looking for, but were just too far away for poor students to consider. So based on my 1972 aerial observations, and with the knowledge of Bruce and Monte’s discovery, we turned to Mount Borah.

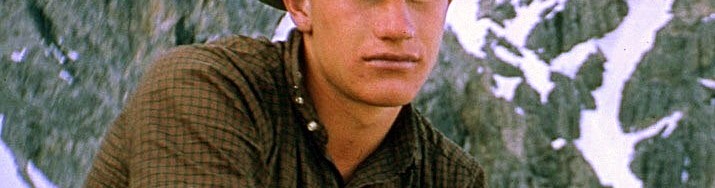

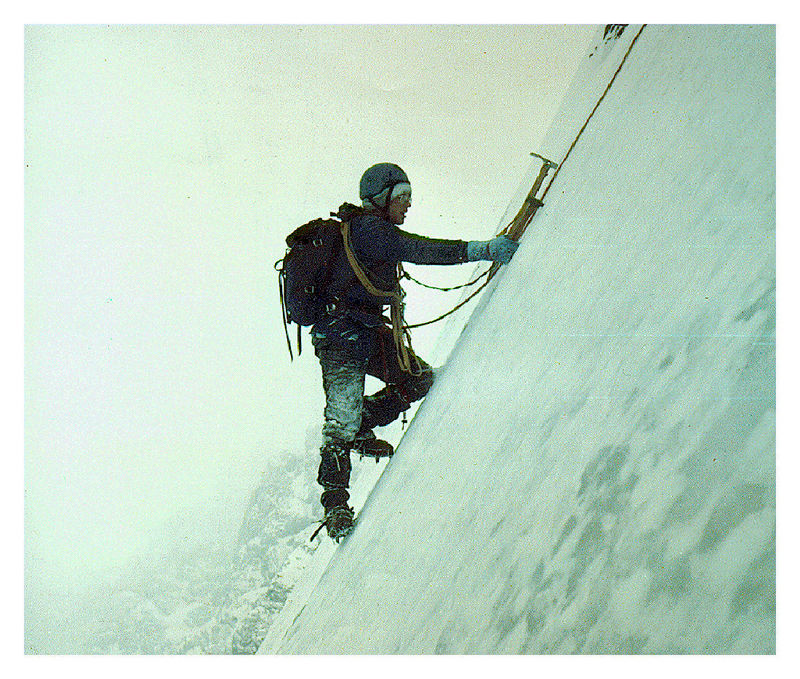

In September 1976, Frank Florence and I made plans to climb Borah’s North Face, but a torrential thunderstorm turned us back before we reached the moraine below the face. Cloud cover obscured the mountain and all we saw was the lower snowfields, leading us to believe that was all we were going to find on this mountain. In late October, Mike Weber and I returned to give it another go. The weather was perfect this time and after climbing the lower cliff band, we finally got a good look at the North Face. The face was covered with a light dusting of snow from the first snowfall of the season. So until we reached the top of the moraine, we were expecting nothing more than a snow climb. At the top of the moraine, Mike and I geared up, and from the very first swing of our ice tools we knew we had finally found what we had been looking for. The ice was thick and rock hard, not brittle like so much of the Winter ice we had climbed before. We half expected the ice would turn to snow the higher we went but it did not. The ice continued all the way to just below the summit. Like Bruce and his discovery of the glacier, we found more than we ever expected.

My partners and I continued to climb the North Face of Mount Borah throughout the 1980s and we just assumed the ice and glacier would always be there. During most of the year, the face was covered with snow but, by the Fall you could count on the underlying ice showing through. On one of our trips in the mid-1980s, we discovered that a massive avalanche had occurred, taking most of the previous Winter’s snowfall with it. Bruce’s snow measuring equipment was wiped out and was carried almost a mile down to where it now sits. Little did we know at the time that we would be part of a small group of climbers who actually got to see, stand, and climb on Idaho’s last, and perhaps only, remaining glacier.

In September 1990, Mike Weber, Curt Olson, and I returned to the North Face expecting to find conditions similar to what we had found for the previous 14 years. We were quickly disappointed when we got close to the base of the North Face. The lower ice fields and the glacier were, for the most part, gone. There was still some remaining old blue ice left on the upper part of the North Face, but the bottom was mostly bare rock.

We were in shock. The glacier and lower ice fields were almost gone. This was the last photo we took of the old blue ice that was estimated to be over 500 years old. In 2009, I was contacted by geologists who were doing a study of the Glaciers of the American West, which included Idaho. As a result of that study, Idaho was found to have no remaining glaciers with the exception of perennial snow fields and a few rock glaciers where all of the ice is underground.

In 2017, I was disappointed to read a trip report that highlighted the demise of snow and ice on the North Face. This news was especially troubling as the 2016-2017 winter resulted in a solid snowpack existing above 8,000 feet in the central mountains in June. Many high-elevation basins had more than twice the normal snowpack. I don’t know what it would take for the ice to come back short of another ice age.