I guess we were the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club (DFC&FC) before anyone, including us, knew. The little guy in the back of my mind liked the way the words fit together. Until the name popped into my head we were simply a group of like-minded climbers who lacked an identifying name. However, on a fateful morning in the mountains of Idaho, adversity transformed us from a nameless, ragged band of climbers into an organization that would accomplish endless deeds of climbing derring-do.

The fateful day was a hot one in late July 1970. We were hiking into Mount Regan above Sawtooth Lake. Our packs were heavy, each with 60-70 pounds of climbing and camping gear. In addition to the heat, it was a humid and windless morning. We were sweating hard and were being chased mercilessly by a full-strength squadron of horseflies.

Flies dive-bombed us incessantly, trying to break through the curtain of insect repellent we had drenched ourselves with. They grew in numbers, until it was difficult to see the sun through the voracious fly swarm above our heads. Frenzied buzzing horseflies became noisily trapped in our long hair and select kamikaze flies would creep between our sweaty fingers to inflict amazingly painful bites.

It was starting to look like we might become the first known case of climbers eaten by flies when suddenly all the horseflies dipped their wings, did a double roll and turned tail. They flew off down-canyon–a roaring cloud of instant misery. The reason for their retreat stood by the trail snarling evilly, shovel in hand. Even horseflies don’t mess with SMOKEY THE BEAR!! Of course, a sudden breeze might have helped too.

We had arrived at the Wilderness Boundary! There beside the plywood Smokey was an 8-foot tall, solid redwood sign proclaiming:

ENTERING SAWTOOTH WILDERNESS AREA

CHALLIS NATIONAL FOREST

PLEASE REGISTER FOR YOUR OWN

PROTECTION!

We had some fun filling out the overly-detailed registration form, but then none of us wanted to put our name on it as group leader. In a moment of inspiration, I exclaimed “Let’s call ourselves the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club” and, since I thought of it, I get to be manager.

We had elections on the spot and Gordon chose to be Social Chairman, Harry Bowron, Treasurer, and Joe Fox, Member at Large. The next day we climbed Mount Regan (which was somewhat challenging) and had a great time. Our mountain fun was just starting. We never had scheduled meetings or dues but, in order to become a member, you had to go climbing with another member. Of course Gordon took his duties as Social Chairman seriously. He was soon adding females to our club. I must admit to being jealous of Gordon’s social skills in the 1970s and 1980s. His girlfriends were always attractive, assertive and intelligent. Gordon was a “babe-magnet” of the first magnitude. Thus, he was the perfect Social Chairman.

The rest is history, and we did climb Mount Regan the next day.

After our spur of the moment start in July 1970, we never had regularly scheduled meetings, but we enjoyed a 4th of July group outing in the Pioneer Range and another outing in 1971, with about 20 friends attending. For the most part, DFC&FC members climbed together in small groups.

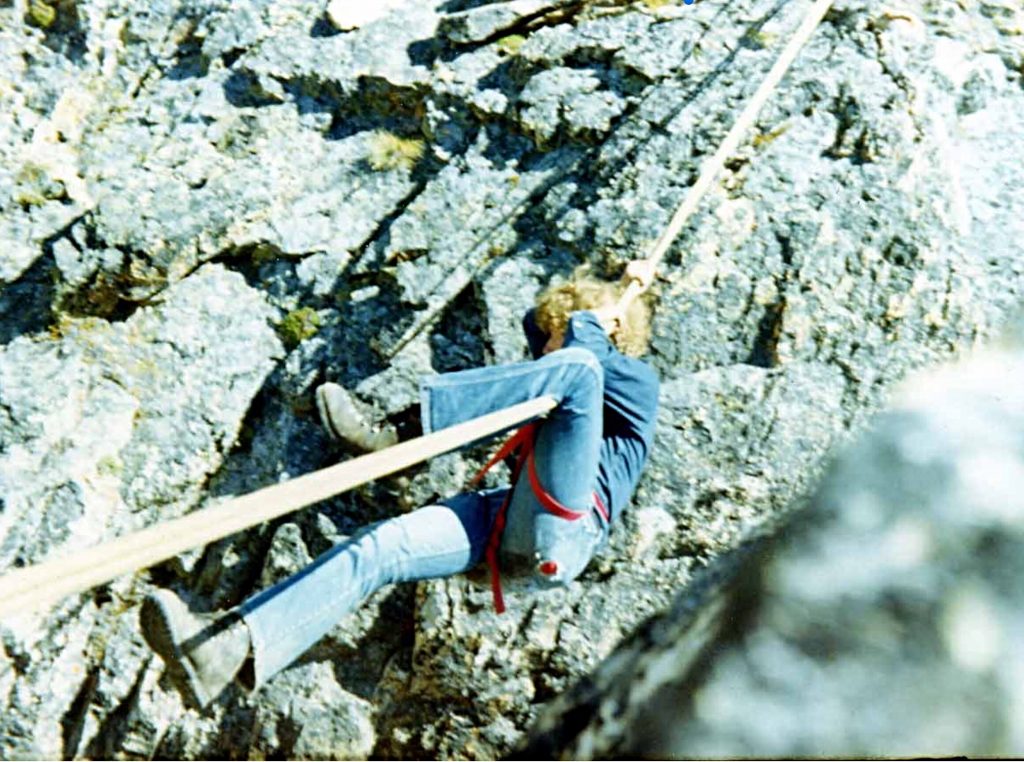

In the early 1970s, Idaho mountaineering was a different world than now. It was a world without good USGS maps, climbing guidebooks, cell phones, GPS devices, an internet to access for climbing information and satellite rescue beacons. Thus, we suffered considerable obstacles to safe and sane mountaineering, but let me assure you, rock climbing and mountaineering in Idaho was a helluva lot more adventurous and a lot more fun then than it is now. Amazingly, although some of our climbing students suffered long scary slides on steep snow slopes, there are no serious climbing injuries or deaths in the history of the DFC&FC.

In keeping with the local ethics of Sawtooth climbing which sought to keep the Sawtooth Range unpublicized, club members did not (for the most part) publish their climbing exploits. Still, members made some impressive ascents and all of us were actively invested in exploring the nearby mountains.

In the early 1970s, Gordon Williams was instrumental in leading groups which pushed the limits of Winter climbing in the Sawtooth Range. There were some setbacks, but under Gordon’s leadership, there were successes. The two most notable Winter first ascents were the Finger of Fate and Mount Heyburn.

Harry Bowron and I completed several notable new routes in 1971 and 1972 in the Sawtooth Mountains, including two new routes to the summit block of Big Baron Spire and a new route on the South Side of Warbonnet. Contrary to local ethics, I did publish an account of a new route I achieved with Mike Paine and Jennifer Jones on Elephant’s Perch in 1967. My ethical breach insured that no other climbers would climb the same route and claim the glory of a first ascent on the biggest wall in the Sawtooths.

The only tangible achievement of the DFC&FC was to restore Pioneer Cabin, which sits on a high ridge east of Sun Valley adjacent to the high peaks of the Pioneer Range, in 1972 and 1973. I was in Moscow, Idaho at the time and had nothing to do with the project. Credit for the rehabilitation goes to Gordon Williams, Robert Ketchum, Chris Puchner and others who donated materials, helicopter time and labor.

Gordon Williams was insistent on painting our club slogan: “The higher you get, the higher you get” on the roof. Somehow, that painted slogan survives on the roof of Pioneer Cabin to this day. Here’s a link to an Idaho Public TV article on it: Pioneer Cabin

Long-term club member John Platt recalls another club slogan he heard while skiing potential avalanche terrain into the Finger of Fate in 1972. “Stay High & Spaced Out.” A high-end outdoor magazine, Adventure Journal, published an article on Pioneer Cabin and the DFC&FC link in their second issue in 2018.

After a high-point with the Pioneer Cabin restoration, the DFC&FC never managed to hold more scheduled events. Nevertheless, members continued to use the name on wilderness registration forms and an informal competition to achieve the most yearly “back-offs” from major rock climbing routes or mountain peaks, persisted into this century. We of the DFC&FC enjoyed fiascos. In the era before decent USGS maps, climbing guidebooks, cell phones, GPS devices, an internet to access for climbing information and satellite rescue beacons, success on routes was not assured and failures were cherished.

In 2001, Gordon Williams hosted a 30th Anniversary party for a surprising number of DFC&FC members. I recall around 20 attendees, including one who flew in from Alaska for the occasion.

In 2012 Matt Leidecker interviewed Gordon Williams, Jacques Bordeleau and me for historical information on notable climbs DFC&FC members had achieved in the Sawtooth Mountains. Leidecker included several paragraphs recounting the club’s history in his fine hiking guide “Exploring The Sawtooths.”

Matt summed up the DFC&FC club achievements in the Sawtooths with a Gordon Williams quote: “I got to thinking what was the shining achievement of our time in the Sawtooths and I came to the conclusion that it was simply to have a good adventure. Once you learn how to do that, you can keep doing it forever.”