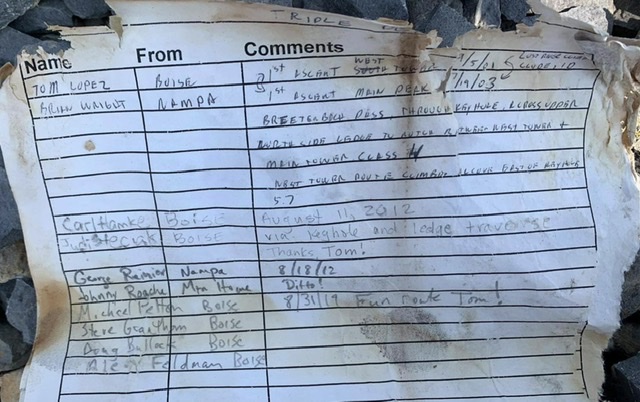

The second edition of the book discussed the then unnamed Triple Peak as follows:

Peak 11280+ 11,280+ feet (Rating unknown)

This complicated tower, the southernmost summit on the Corruption/Breitenbach divide, is probably unclimbed. It is located 1.5 miles northeast of Mount Breitenbach. It is the steepest, most rotten looking summit in the entire range. Access the base of the peak from Breitenbach Pass [(A)(6.1)(a) or (C)(3.2)(a)]. USGS Leatherman Peak

It was the only peak that I put in the book that I was sure had never been climbed. I thought I would give others a chance to make the first ascent but I had every intention of being the first to reach its summit.

The peak first caught my attention when I reached the top of Mount Breitenbach in 1991. The peak’s multiple towers dominated the view to the northeast. It looked like a difficult climbing problem. Triple Peak is a complicated summit located on the treacherous Mount Corruption/Breitenbach Divide. Triple Peak is composed primarily of Challis Volcanic rock which was deposited on top of the Lost River Range’s limestone base. The rock is as rotten you can find in Idaho. It was clear that the peak’s poor rock quality would be the biggest obstacle facing climbers.

I mentally added the peak to my exceedingly long climbing todo list. At this time I was working on the second edition of the guidebook and many other peaks across the state had a higher priority than that rotten towers I observed from Breitenbach’s summit.

Eight years later the second edition of my book was scheduled to hit the books stores in late Summer 2000. I decided I should make an attempt before the book was sent to the printer or someone else got ahold of the new edition and beat me to it. Little did I know that it would take me four tries over four years to discover the secrets of the towers that make up the peak.

The first attempt took place in late June of 1996 with Scott Mcleasch. We were surprised to find that unusually high water would keep us from driving across either Dry Creek or the upper Pahsimeroi. We turned to plan B which was to begin from West Fork Burnt Creek, climb Cleft Peak and then traverse the connecting ridge to Triple Peak. This was a long approach and I was not having a great day. When we reached the summit of Cleft Peak, the view of the connecting ridge and Triple Peak’s east tower was not encouraging. We decided to call it a day. Cleft was a nice consolation prize and at least I learned that the traverse, while it might be work, was not an efficient route to make the summit.

The second attempt took place in 2000 with Brian and Karen Wright. This time we were able to ford Dry Creek and reach the trailhead. At one time a good trail climbed up Dry Creek, crossed Breitenbach Pass and descended down the Pahsimeroi River. In 2000 the trail had not been maintained in many years. We hiked up the poorly maintained trail toward Breitenbach Pass. At 8,600 feet we decided to leave the trail and climb the talus directly to the base of the east face of the summit block aiming for its southwest corner. It was a long, loose and tiring trudge. The higher we got, the looser the talus got. We finally reached the summit block and began looking for a line we could climb. The block’s face was mostly vertical. We tried a crack and a gully without finding a suitable route. We then climbed around to the peak’s south ridge and spotted a suitable line. However, it was now late in the day and, as working stiffs, we had to call it a day.

On the third try in 2001 Brian and I backpacked up the Pahsimeroi River and set up a camp at 8,800 feet. The next day we hiked to Breitenbach Pass utilizing the trail where it existed and the mostly open slopes where the trail disappeared. From the pass we had a good view up the peak’s southwest ridge. The tower that loomed above us looked imposing but there was a split in the vertical wall that looked like a potential line to start our ascent. We hiked up to the base of the tower and roped up.

I started up the steep gully that cut the tower’s face cognizant that the rotten rock was not conducive to roped climbing. First, I traversed to the right off the ridge top climbing over boulders and talus for about 150 feet to the base of the steep, slippery, debris-filled gully that split the face. I carefully climbed up the gully crossing loose talus in places and a series of hard ledges covered with loose rock. At the top of the gully, I was in an alcove capped by a 12-foot-high Class 3-4 wall. At the top of the wall I found a narrow hole or keyhole that exited out of the alcove to the northeast. I set an anchor and looked through the keyhole and discovered we had options to continue the ascent. I put Brian on belay and brought him up.

We climbed through the keyhole and continued to climb up, unroped, across Class 2-3 debris until we found ourselves at the base of the southwestern most tower’s highest point. Above us was a vertical 75-foot wall shaped like an open book. The wall’s was composed of hard or at least harder rock than we had already crossed. It appeared this feature would lead to the top of the tower without too much difficulty. To the left, we could see a ledge system that appeared to traverse the base of tower’s north face. Access to this ledge would involve crossing a steep rotten gully and climbing a 25-foot-high nearly vertical wall of dirt and debris. From our perch any further the view northeast along the summit ridge was blocked.

Since we had no confirmation of which of the peak’s three towers was actually the highest (we did suspect the middle tower was the highest) we debated our two options. First, we could climb the tower we were on which would at least help clarify the highest point issue. Second we could descend down the very steep, loose debris filled gully and see if we could locate a route out of the gully at some point which would allow us to traverse northeast toward the notch between the West Tower on and the middle tower. In sum we had to choose between a descent of unknown length into the unknown on loose and unconsolidated crud or a climb to the top of the tower we were on relatively hard rock. It really was not a choice that was hard to make. We did not consider attempting to climb out of the gully via the 25-foot dirt wall.

We set an anchor. I put Brian on belay and he made short work of the climb. We rated this short 75-foot section at 5.7. He belayed me up. As I reached the top I detected disappointment on Brian’s face. He didn’t say anything. He just point to the next tower which was undoubtedly higher. Although it was higher it was obviously a Class 2 scramble from the intervening notch. Between us and the notch was a hundred foot vertical drop, a drop that didn’t look conducive to down climbing. “Okay,” I said, we need to rappel down the 100 foot drop into the notch.

We spent the next thirty minutes trying figure out a safe way to set up a bomb proof rappel anchor cognizant that we would also have to use the anchor to safely protect ourselves when we had to climb back up wall on our return. There was horn we could safely use to rappel down our line of ascent but it’s shape would not work for a rappel down into the notch. The rope would slide off it. Our effort to set an anchor proved futile. It was impossible for us to set an anchor to rappel into the notch between the two towers with the equipment we brought.

While the route from the notch to the summit looked an easy walk, it was late on Sunday afternoon, we still had to backpack out to the truck, make the six hour drive back to Boise and we both had to work the next day. We gave up and vowed to return. The Summer passed by without an opportunity or the desire to return.

In 2002, I broke my leg sliding into second base in a softball tournament in early June. (I was safe by the way). After surgery, recuperating and physical therapy it was late September and my leg was too weak for serious climbing. I settled for easier climbing until the snow flew.

Finally, on July 19, 2003 Brian and I found ourselves once again at the base of the southwestern most tower. Based on our prior adventures, we decided that the best route was to climb the southwestern tower again, set up some south of Rube Goldberg rappel anchor and rappel into the intervening gap and finish the climb. We took an extra rope, a bolt kit and 100 feet of sling, ascenders in hopes that we could fashion a safe rappel anchor someplace on the tower’s rotten summit.

Once again we packed up the Pahsimeroi River and set up camp. In the morning we hiked up to Breitenbach Pass and then hiked northeast up the ridge to the base of the wowed. This time we climbed the dirty gully to the keyhole without roping up. We climbed through the keyhole and up to the base of the open book.

While Brian was setting up an anchor to begin the climb up the open book, I stared at the ledge to the rotten 25-foot wall blocking the way and the view. After wondering for two years what was on the other side of the wall and whether it connected with the ledge I made up my mind. I decided to take a look. Brian put me on belay and I edged across to the gully to the base of the wall and started up. It was like climbing an overhanging road cut. Dirt and rocks streamed down around me but it was not as bad as I had imagined two years earlier. When I reached the top and looked over the top, I found a rather wide ledge that traversed the remaining section of the Towers north face which lead into the notch. From that point on, the climb was a walk across talus and boulders.

As we reached the summit, the East Tower came into view. We could not say with certainty that we were on the highest point. We had to check with a spirit level to be certain that we had the first ascent.

lower than the summit.

in the background.

Next: Sierra Nevada Day Hiking