Editor’s Note: The following report by Wes Collins documents his remarkable Lost River Range traverse. His effort no doubt included a number of first ascents. His achievement is one for the ages. All the photos are by Wes.

Last Winter, I traded several emails with Bob Boyles and Frank Florence who both planned on making the trip with me. We decided to hammer it out in a leisurely 4-day trip in late Spring while we could still melt snow for water. However, life kept interfering with our 3 different schedules while Spring came and went as did the snow and the end of our plans. Reluctantly, we decided to put it off for another year but when September rolled around, I made a snap decision to drop everything and solo the traverse. Prior to this time, I had stashed water along the route and only had to iron things out with my own schedule. On a Saturday (3 days later), I was on my way up Mount Borah after leaving a rig parked at the base of Lost River Mountain. The trailhead parking/camping lot was overflowing and there were cars parked on the road all the way past the outhouse. A few hundred yards up the trail I ran into 3 climbers from Idaho (Tracy, Nate and Nashina) and I chatted with them all the way up. The newly-finished trail makes the approach much nicer.

The first hiccup in the trip happened when we got to Chicken-Out saddle, I was climbing down the last little rock knob when my only Nalgene bottle popped out of my pack pocket and took a long, LONG tumble out of sight down the South Side of the col. I immediately thought I’m not going down there to look for that. I had a one liter disposable water bottle that I could make due and I was in a hurry to start the trip beyond Mount Borah.

I stashed my heavy pack on the South Side of Chicken-Out Saddle and, with the load off my back, I practically floated to the summit where a large crowd was lounging in the sun. My adopted crew must have felt bad for me sans pack and plied me with food and drink. Cody Feuz even chipped in. I only stayed on the summit for a few minutes. I always enjoy the company of other mountain people and knew I’d be solo for days but I was anxious to be on my way. Too anxious perhaps. Fifteen minutes after leaving the summit and nearly to the big saddle, I tripped over my own feet and face-planted in a rare patch of soft gravel. My only fall, thankfully.

When I got back to Chicken-Out Saddle, I hopped off the South Col without giving it a second thought. I knew I needed that damn Nalgene bottle but, more than that, I was not going to leave trash on the mountain. I found it WAY down the chute. It had tumbled at least 150 yards but was miraculously intact. I made it back to my pack just in time to see Tracy, Nate and Nashina cruise over Chicken-Out Saddle on their way down.

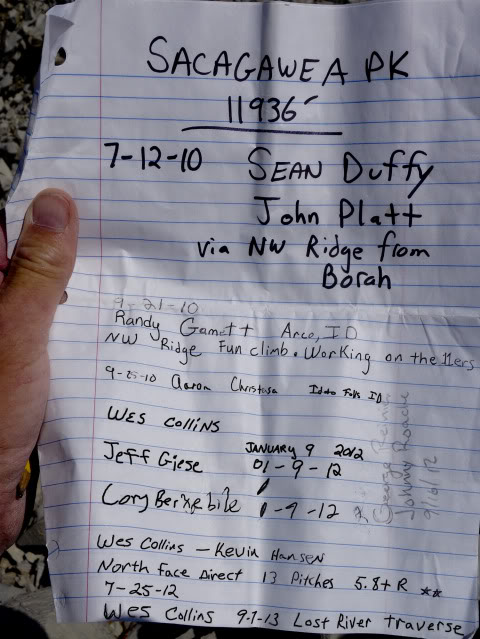

The trip over to Sacajawea was uneventful but fun. There are a few alternatives to get to the top but they all involve Class 4 scrambling. My favorite is to stick to the ridge. The rock quality is great and the exposure is awesome.

This was one of the few registers I opened in 4 days. I shouldn’t be mystified by this summit’s lack of visitors even though its right next-door to Mount Borah. There are other mountains to climb. Bigger mountains in different states. I should be more mystified by my own lack of imagination. What can I say. This range has an addictive nature and it still seems vast to me.

This descent to the Mount Idaho saddle looks like a straightforward scree-ski but sections of slab rock lie just under the surface, making this a slow and dreary slog. I had been down this side twice before and both times had been lured to the more stable-looking rocks on the ridge, but they are quite rotten and even slower going. This time, I just put my head down and followed the chute.

I visited Merriam Lake several times in May through July and, on one of those trips, I stashed 3 gallons of water collected from snow melt just above the upper lake and then packed them up to the ridge. With plenty of water and a great view, camp below Mount Idaho was pretty comfortable.

In the morning, I stayed in my sleeping bag until the sun warmed things up a bit and then headed up the ridge toward the summit of Mount Idaho. Several years ago, my first trip to the top of this mountain was up the North Face and I climbed/rappelled down the North Ridge so I knew what to expect. To avoid those steep sections, I climbed out onto the Northwest Side. There are several sections of Class 4 climbing and some Class 5 but the rock was pretty nice. With good route finding, most of that steeper stuff could be avoided especially if you stayed closer to a broken gully system near the North Ridge.

The ridge from Idaho to the summit Peak 11967 was all new ground to me. I’d looked at it several times in the past and, although there are a few jagged sections, it looked passable. I tried to stay close to the ridgeline and mounted several Class 4-5 sections, but all of that could be traded for Class 3 on the West Side of the crest.

I burned up a good part of the day in the pinnacles and didn’t cross the South Summit of Peak 11967 until about 2:00PM. To save time, I avoided the worst parts of the ridge to White Cap Peak by staying on the West Side.

Some of the ridge sections were unavoidable without a down-climb out onto the West Side. The East Side of the crest was generally too steep throughout this trip. There were a few mandatory Class 4 sections but I was able to avoid anything steeper.

I filled 3 gallons of water earlier from a spring above the Elkhorn trailhead and stashed them at Leatherman Pass. I put a few drops of bleach in two of the jugs and planned on using the other jug for cooking and coffee. The unpurified jug had a different lid so I wasn’t worried about accidentally drinking out of it. By the time I got to the summit of White Cap Peak, I was dehydrated. I hustled down to the stash and immediately took a good long pull off the first jug I came to. I only realized my mistake after I’d drunk at least a quart of the unpurified spring water. I wasn’t too worried though. It smelled OK and tasted fine.

I cooked a double-sized Mountain House meal and decided that I had time to get over the top of Leatherman Peak and into the saddle below Bad Rock Peak. By the time I hit the summit, I was feeling a little off my game. I told myself that it was just altitude combined with letting myself get a little dehydrated, but I was thinking I may have screwed up. Two years earlier, I’d seen mountain sheep drinking from the origins of that spring a few hundred yards above my collection point. There wasn’t anything I could do about it. If I got sick, I’d have to go down no matter which side of the peak I was on.

It was getting late and having been down the South Side of Leatherman Peak twice before, I knew the next several hundred yards would be tricky and slow. The trick is to avoid getting cliffed out and having to climb back up for a re-do. Usually this involves ignoring the obvious somewhat easier path half way down and sticking to a few rotten Class 4 cliff bands to your left. In my case, I used a rope and made 2 key rappels on the ridge proper.

Bad Rock camp was pretty comfortable and, like the first night, there was very little wind. I found a nice wide sheep bed to sleep on. In the morning, I woke up to a heavy layer of frost on my bag but it was another bluebird day. My stomach was still off but I definitely had not caught a bug like giardia. I forced a couple granola bars down and headed off, knowing this would be the toughest stretch.

I looked for a register on the summit of Bad Rock Peak but it’s gone missing. I have descended the South Face several years earlier and its every bit as difficult as the descent on Leatherman Peak. The same rule applies: stay on the ridge or face a long climb back up to the crest. I sat on the summit looking at the ridge beyond for a long time. I knew that it had been done in the past and that put me at ease. I REALLY wanted the summit of Mount Church from the ridge. I’ve heard rumors of it being climbed and was eager to follow.

Thirteen years ago, I traversed from Leatherman Peak to Mount Church by dropping off Bad Rock Peak and climbing Mount Church via its North Face which is an easier/faster alternative. On that trip, I studied the ridge to the summit and decided that it was impossible. However, when I got to the summit I read in the register that a solo mountaineer a few weeks ahead of me had done just that. I was bitterly disappointed in not giving it a chance and vowed to return and finish it.

I cliffed out twice while trying to get to the start of the ridge and both times involved a pretty long climb back up to start over. Once on the ridge, the big slab towers I was worried about along the first two-thirds of the traverse proved nothing more than easy Class 3 and I made good time by traversing on their Northeast slabs. The last two (and biggest) were much worse. I skipped the first one by cutting around its Northeast Side but the last one would have none of that and it turned out to be the sketchiest bit of the whole trip.

I planned on climbing right into the col between the towers but the closer I got, the more I realized it was a dead end. From the col, the ridge was blocked by a steep 80-foot buttress. To top it off, the rock quality was terrible. Instead of going all the way to the col, I managed to make my way up a line of weakness just below the crest. But there was a sequence of easy, but exposed, Class 5 steps and holds that could have (should have) blown out. By the time I got back to easier ground, I was pretty rattled. An easier solution would have been to traverse 30 feet lower and past the buttress.

Back on the ridge, I continued right up to the face and found a place to choke down a handful of cookies. I studied possible lines but was absolutely unable to find anything suitable to start up. I knew if I could make it past the first cliff band, I’d have a good shot at the upper mountain. But that first 30-40 feet of rotten nastiness over a fatal fall zone really needed a belay. I worked my way back and forth across the ridge, hoping to find the key but it just did not materialize.

On one foray, I continued well out onto the West Side of the crest thinking there might be something, but finally admitted defeat. I may have been too demoralized by clawing my way up the rotten tower and felt I’d pushed my luck far enough for this trip. But as I write this, I still believe I made the right choice. At any rate, it was a huge letdown. I traversed the entire West Face looking for a break in the cliffs but, for the most part, they just got bigger and steeper. This long side hill took an enormous amount of time and, in the end, I was close enough to the Church/Donaldson tarn (located on the standard route at 8,600 feet) that I dropped down and tanked up at the greenish pond.

I finished off the water in my trusty Nalgene bottle and filled it along with the gallon jug I had stashed in my pack with boiled water. It was then that I found a split in the bottom of the now-useless jug and realized things were going to get tougher. I climbed back to the crest, dumped everything but the stove, Nalgene bottle and cooker out of my pack and cruised to the top of Mount Church. Earlier, while on top of Bad Rock Peak, I spotted a small snow patch near the summit of Mount Church and I was able to refill again there. I made it to the summit of Donaldson Peak in mid-afternoon.

Although I intended to make another water cache in the saddle between Donaldson Peak and No Regret Peak, I got lazy and never made it happen. I was still on familiar ground and made quick work out of the long ridge to the summit of No Regret Peak. There are several small sections of Class 3 surprises along this segment and, luckily, I remembered to traverse around the one 70-foot drop-off at the start of the final climb up to the top. If you miss this, it’s a substantial down-climb to get back around it.

From the top of No Regret Peak to the base of Mount Breitenbach, I was on my second and final stretch of unfamiliar ground. I planned on camping on the ridge just below the big 200-foot tower that blocks access to the top from the ridge. I did not make it far before I came to the first mandatory rappel. It was an easy 40-footer but I had to leave a nut and loop of 6MM cord behind. I pulled my rope and continued to the second and (what I thought) last rappel.

It was too long to do as a double-rope rappel, so I wound up leaving my rope as well as a large nut and small cam attached to the anchor. I knew this meant a return trip in the near future to collect gear, but it would have meant a long down-and-up climb to bypass the drop. I continued on and, as luck would have it, bumped into another straight 30-foot drop. I had to do the long back-and-forth after all. In fact, there were several tough spots on the way to Mount Breitenbach and it eventually ate up the rest of the afternoon.

With less than 200 yards to go, I ran into yet another 50-foot impassable drop. Again, the only way past it would require a long descent and return. I really wanted to sleep on the crest but there was not a suitable place in sight. I shot one last photo of Peak 11280 and headed down. What the hell, I needed water and I knew Jones Creek started pretty high up.

The descent went pretty slow because I was still looking for a short way around the drop and back to the crest. By the time I hit the first springs, it was pretty dark. I was sick from not drinking enough water and worse from drinking Leatherman water. I stuck my head in the creek and took a good long pull, then filled and drank a Nalgene bottle. To hell with boiling it. I continued downward, looking for a place to bivy and noticed my headlamp needed new batteries.

I pulled my spares out and found they were dead. I returned the dying ones and made the best of them, but it was not long until I was blindly stumbling around in the boulders. Just about the time I was admitting to myself I’d be doing a dreaded sitting-bivy, I found a flat rock on the lip of a 10-foot waterfall and, after moving a few rocks, I had a nice little nest. For dinner, I ate a handful of cookies as my stomach could not do another freeze-dried feast.

Sleeping that close to the creek was music to my dehydrated ears and, despite the rough bivy spot, I slept very well. I had descended a long way down from the crest and, while drifting off to sleep, I started entertaining the thought of bailing out for the truck at first light. My headlamp was dead, my water container was inadequate, and I was feeling pretty ill.

In the morning, I laughed at the idea of bailing. I had a good night’s sleep and a handful of almonds with my coffee improved my disposition even more. I hung around camp for a good 3 hours, drinking water and reading the book I brought. Eventually I gathered up my gear (including the useless water jug) and was standing on top of Mount Breitenbach in just over 2 hours.

The hike around this cliff on the way to the top (A). The first rappel (B). The second rappel (C). The first hike down and back up (D). The Second down and up (E). The last impassable cliff (F).

In my hurry the night before, I forgot to take a photo of Mount Breitenbach from the last cliff but I’d been between the summit and the last cliff several years earlier. There is a 200-foot steep buttress that is bypassed on its West Side by a short but exposed Class 4 wiggle.

I was on familiar ground once again. This section is easily the longest stretch of ridge between peaks and, although a good portion of it is easy hiking, there are several sections of Class 3- 4 rottenness. A broken sheep trail covers much of the distance on the West Side of the crest, making things even easier.

The meat of this segment starts just before the final slopes to the summit and staying on or near the ridge can be perplexing. I’d describe it as climbing layer cakes of crap by finding the way up short cliffs and then searching for a way back down on the other side. There are a few places one has to leave the ridge (usually to the West Slopes) and climb around towers and obstacles but its all Class 3-4 unless you want to make it harder. On a previous trip, I’d bypassed this crux by climbing out to the right of the cliffs. This time I decided to explore to the left. It was all pretty rotten but fairly straightforward excluding one 15-foot section of rotten Class 5 over a steep scree-covered ledge. Beyond this tower, its Class 2 all the way to the truck.

I was in fairly poor shape at this point. My water was long gone and all I was able to eat was the little pack of almonds. I sat on top and forced down some gorp for the descent while thinking about my return to things less significant than watching every step. I wondered how many miles I had covered and then decided it didn’t really matter. The miles covered up there are like dog years–1 seems like 7. A week later, I was back on top of No Regret Peak to retrieve my rope and gear. Three weeks after that, I collected my empty water jugs at Leatherman Pass as well as a golf club I brought down from the top of White Cap Peak. The water bottles below Mount Idaho will have to wait until Spring, I guess.

This was the kit I took and I only used it for rappels. The only place I’d have used it as a self-belay was at the base of Mount Church but I’d have had to set the base anchor pretty far from the climbing. The rope is a 9.1MM I’ve had for years and never used. I cut it in half to save weight. I used the blue gear sling as a swami belt and cut up pieces of the 6MM line for rap anchors.

Author’s Note. This is part trip report and part guide. I’ve left out a good many details in the hopes of preserving some of its mystique but I included reduced size photos of the entire ridge system. Get a hold of me if you want to see a larger version of any of them. (20MB)

Many of us have talked and schemed about doing this traverse and although there’s a lot of information out there, it mostly deals with individual sections. I know some have finished it and many have finished sections of it. If it’s on your wish list, I can tell you that it’s well worth the time and effort.