Idaho has nine summits that reach over 12,000 feet and all but two lie within the Lost River Range in central Idaho. Idaho’s tallest and most visited peak, Mt Borah (12,662’), is located in the central section of the range. As the state highpoint, it is also very popular. During the summer months, it is not unusual to see a full parking lot and 50 or more people attempting to climb the mountain by its most popular route, the Southwest Ridge, or “Chicken-Out-Ridge” as it is more commonly known. For some classic snow or ice climbing, Borah also offers several hidden gems on its North Face, including routes written up in past editions of this journal. In spite of all of the traffic the mountain has seen, the remote East Face remained relatively unexplored and unclimbed until the summer of 2011.

Geology

Idaho’s Lost River Range is an actively uplifting fault-block at the northern end of the Basin and Range province. Extensional faulting has lifted the range relative to the down-dropped Big Lost River basin on its west side, producing steep ridges and slopes essentially devoid of foothills. Interior and eastern regions of the range are deeply incised by the Pahsimeroi and Little Lost Rivers. Most of the range, particularly in the central and southern regions, consists of thick layers of Paleozoic limestone and dolomite. Multiple episodes of tectonic deformation have resulted in dramatic open to isoclinal folding at a scale of meters to kilometers. Glaciation has carved numerous cirques throughout the range and alpine lake basins are scattered in the central and eastern portions. These combined activities have created an impressive assortment of large, high angled faces with western, northern, and eastern aspects.

Background

I first visited the eastern side of the Lost River Range (The Pahsimeroi Valley) in 1972, while working on a helicopter contract for the Forest Service. Flying through the range provided me a view that few ever get to see. While all of the range is impressive from the eastern side, one face stood out from the others. When our contract with the USFS finished at the end of summer, I took a break from the 24/7 aviation life I was accustomed to. During this down-time, I happened to notice an ad for an introductory rock climbing class and thought, “Wow. Cool. Ropes and everything, I’m game for this!” I talked a couple of friends into joining me for the class. After completing our class, we were ready to test our newly learned skills on a real mountain but winter soon arrived and we put our plans aside until the next summer.

Summer came late in 1973. It wasn’t until the end of June that we were able to get in for a closer look at the East Face. As the morning sun warmed the snow high in the cirque, we watched slide after slide tear loose and nail virtually every approach to the mountain. Along with the snow slides came a lot of rock fall as well. After sitting and studying the face, it looked to be climbable. There was no doubt, however, that the attempt would have to be made during the dry season. In 1974 we returned for another exploratory trip and picked out a line on the face that followed some water streaks in a nearly straight path to the summit. We decided that this was the route we would attempt on our next visit.

A couple of years passed. In trying to sell potential climbing partners, I described this face as “Idaho’s Eiger” but at the time, the range had no technical rock routes. Idaho has so much fine granite it was hard to justify a trip to the Lost Rivers, where the limestone rock had a reputation for being nothing but choss. In the fall of 1975, Mike Weber and I decided to throw caution to the wind and give this face a serious attempt. We loaded up all of the gear we thought we’d need and made the brutal drive to the end of the road up the West Fork of the Pahsimeroi River. Hiking through open sagebrush, we made quick work of the approach and found a nice grass-covered spot for our camp at the lower tarn just above timberline. Curious to see the face up close, we grabbed our crampons and axes and headed up the snow and ice to where the bare rock began. Just as we were approaching the final section of snow and the start of our proposed route, we heard a rumble from above, freezing us in our tracks. A Volkswagen-sized rock was flip-flopping down the face. Within seconds, it reached terminal velocity bouncing back and forth down the face. We stood motionless in our stances trying to figure out if we should go left, right, or just clasp our hands and pray. Fortunately, the rock deflected about 40 feet to our right. We just stood there watching it tear up snow and bounce to the flats and the tarn at the bottom of the cirque. We tried to convince each other that the face would be frozen up by morning but neither of us was to be convinced. Around 2:00 am we were startled awake by a blinding flash of light and milliseconds later, a rumble of thunder. We both knew our chances to climb were most likely over, so we pretended to go back to sleep. Within minutes, the rain was falling at a rate of an inch or two an hour, and shortly afterward our campsite became a flood zone. We stayed in the tent until it was surrounded by flowing water, our cue to get the hell out of there.

For decades after that ill-fated attempt, my climbing partners and I continued to explore and put up routes in the range. Despite those many visits, we never made it back to the cirque. I pretty much wrote off the East Face as being a very dangerous place and that kind of risk no longer appealed to me. Also, as time progressed, I gained the impression that sport climbing and bolted routes on established climbs were the “new norm” and the pioneering of new alpine routes seemed to have gone by the wayside. It wasn’t until the spring of 2011, during a discussion of Lost River climbs on the Idaho Summits web forum that a new spark of interest began. When I first described the East Face cirque, most local climbers did not know what I was talking about. This, despite most of them having climbed Mt Borah multiple times. One did, though. After reading my description of the face, Wes Collins, a local climber and native of the area, immediately became interested. Soon, a new discussion started about taking a trip to the cirque.

First Ascent – The Dirty Traverse Grade III 5.4

Wes Collins (solo) July 2011

Wes couldn’t wait to see the face up close so he took off on an exploratory trip with his wife and dog. This trip in 2011 started as a recon, but Wes found himself drawn to the face like a magnet. The following is Wes’ account of the first ascent.

Bob got me all fired up to get a look at the eastern cirque and what he described as Idaho’s Eiger. I certainly wasn’t disappointed. Susan and I planned the trip as a leisurely backpack into Lake 10,204 to take in the views, but I tossed an axe and some light crampons in the truck just in case.

I spent a lot of time looking at the face before I even thought about a spot for the tent. Stupidly, I’d left my axe and spikes in the truck, but at this point I knew I was going to make a serious try for the summit. It didn’t take long to pick out a couple possibilities, but the most probable line would involve a long traverse across a talus-covered ledge on the lower face. I started thinking of the route as the Dirty Traverse before I even put my boots on it. Morning was an easy laid-back affair. We sipped coffee and we watched the sun line slowly make its way down the mountain. I had to wait until nearly 10:00 before the snow softened enough for step kicking. The first, lower snowfield was pretty firm, but the second was much softer.

I’d found a nice tooth-shaped chunk of limestone that probably wouldn’t have done much more than keep my feet down hill if I took a fall. I was on my own, but it was still embarrassing to have the damn thing in my hand and I had to keep fighting the urge to hide it in my pocket. At the top of the snow, the randkluft was several meters deep and the first tentative moves on rock over the blackness below felt pretty exposed. The rock, however, was surprisingly solid and clean.

The scramble to the traverse ledge was fairly sustained Class 4, but the rock was good enough to make me forget about the exposure and enjoy the ride. The traverse ledge was quite tedious though and I wasn’t sure it would go all the way to the ridge until I got there.

Once on the ridge I made my way up an easy Class 5 seventy foot buttress but it could have been easily bypassed by scrambling around its west side. Most of the ridge above the traverse is Class 3 or easier.

As I continued up the ridge, my doubts got bigger. The entire north side of the East Ridge is very tall and overhung in several places. More and more I suspected it would dead-end into the headwall but at the last possible minute, a tiny col opened up onto the uppermost ledge that crosses the East Face. It wasn’t till that moment that I knew the ridge would go all the way. Splattski summed it up nicely in his trip report of JT peak as the almost magical opening of doors as you climb. This was one of the most fun parts of this outing. I couldn’t agree more.

The descent follows the standard route down the mountain to the big saddle at 11,800. From there, I dropped into the cirque that takes in the south side of Borah and Mt. Sacajawea. There are several sections of Class 3/4 scrambling over short but loose cliff bands and several linkable snowfields, but the glissade run-out potential is pretty dangerous on most of the snowfields. At the 10,400 contour the angle eases up. From there I hiked down and around the bottom of the East Ridge and finally back up to camp.

The East Face Direct III 5.9

First Ascent Sept 24, 2011 Wes Collins, Kevin Hansen

Second Ascent Sept 19, 2013 Kevin Hansen, Larry Kloepfer

Start at the highest glacial lake in the East cirque and walk around the north side of the lake for easiest access. Angle your way around the bottom snow field and trudge your way up the scree until you reach the first rock band. This is an easy Class 2-3 scramble for 20 meters or so. Once on top, pick your path of least suffering up the scree to the bottom of the snowfield. Depending on where you choose, this class 2 scree slope is not friendly. Loose dirt and gravel are stacked at a 50 degree angle for a few hundred feet. Once at the toe of the snow field, find a place to strap on your spikes. The slope is around 45 degrees and it is wise to bring crampons. Depending on snow conditions, an alpine ice axe could help. Hop the randkluft and get onto the face. From here the world is yours. At first sight it looks like 80 percent of the East Face is 5.6 to 5.7 climbing which is a good rating for the first 4-5 pitches. East Face Direct follows a dark water streak that passes just left of the top of the “Super S” as Kevin called it. The “Super S” is a large obvious fold in the rock strata that composes the lower right quarter of the East Face. At any time, a team could climb side ways (off route) to the right or left a few hundred feet to avoid the more difficult sections. The direct route stays plumb with the top, following the dark water streak to find the best rock. Because most of the climbing is 5.6 – 5.7, groups may choose to simu-climb many of the pitches. Teams that wish to set up a solid anchor every rope length could discover the route is close to 9-10 pitches. As with all mountaineering, speed is safety. Several class 2-3 scree slopes divide the rock pitches. One short pitch was a solid 5.9 with a protection less small overhang. It’s the finest part of the route. Once past the final head wall, put the rope away and enjoy the last 300 feet of class 2-3 scrambling to the summit.

East Face/Northeast Ridge Variation III 5.6 WI2

First Ascent – July 25, 2012 Bob Boyles, Frank Florence

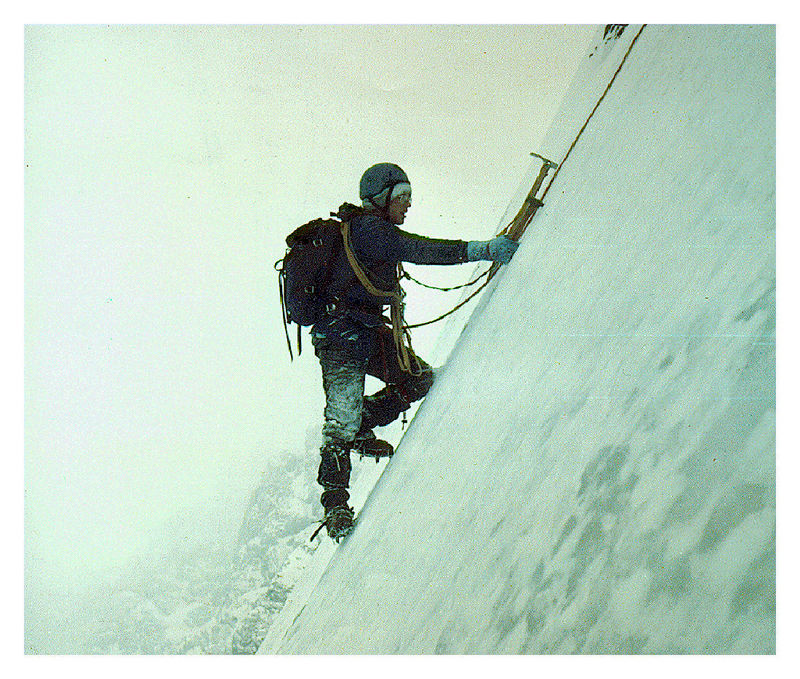

While this route is not overly difficult, it does require a willingness to climb with long run-outs and minimal protection both at belays and while leading. Many of our belays were protected with a single piece of gear and most pitches only allowed for a few placements. Rockfall, both self-initiated and trundled from the summit is an ever present danger on this route.

The route starts slightly to the right of Wes Collins’ Dirty Traverse route and follows the slab like ramps for about 6 pitches of 4th and low to moderate 5th class climbing until you reach the ledge system that allows for an exit to the Northeast Ridge. From there we climbed 2 pitches of very steep snow and joined the ridge. On the Northeast Ridge we encountered a short section of water ice (WI2) and several more pitches of moderate 5th class climbing until just below the summit, where it turns to easy, but very loose 3rd and 4th class climbing.

This route is probably best done when there is some remaining snow to cover loose scree and talus (June – July) and during some years it may not be climbable at all due to the large cornice that can form and block the narrow exit to the Northeast Ridge. Parties willing to solo or simu-climb can reduce the overall number of pitches required on this route.