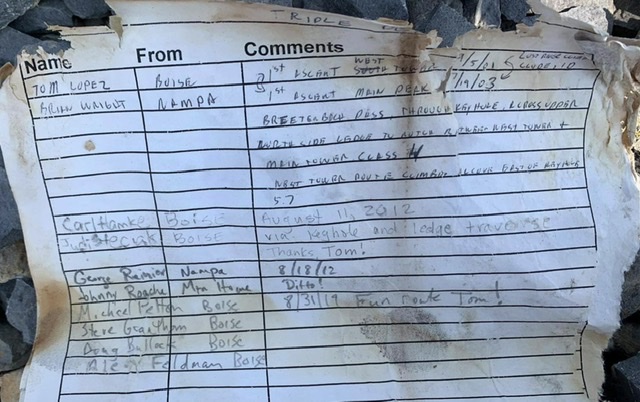

[This article was first published in Idaho Magazine, July 2022.]

The Peak That Got Away

Lady and I gotten along just fine for about half of the five-day horseback trip up the South Fork of the Payette River, until she bolted off the trail into Lodgepole pines. She was at full gallop and I had to lie flat on the saddle to keep from getting knocked off by low-lying tree limbs. After I finally managed to stop her and we trotted back up to the trail, the outfitters quickly found the cause of her behavior. A yellow jacket had burrowed under her saddle blanket and she was getting stung repeatedly. Other than this incident, Lady and I became good friends, and she impressed me with her calm demeanor and backcountry skills. I had ridden a few times in my youth but had never spent a full eight hours on the back of a horse, so I was in for a surprise after dismounting at the end of a long day. It took me a full day to walk normally again and by then, I had nothing but respect for those who make a living on horseback.

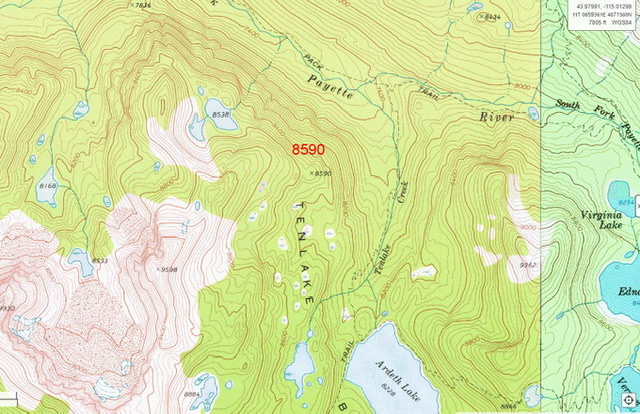

This was September 1973, and I had been invited on the trip by the Carson family. When the outfitter assigned the horses that we would ride based on our experience and the personalities of the animals, he told me, “You’ll ride Lady. She’s a little feisty but she’s a good, sure-footed horse.” We started from the stables at Grandjean, from where we would ride a loop around Virginia, Edna, and Vernon Lakes in the Tenlake Basin before reaching base camp at Ardeth Lake.

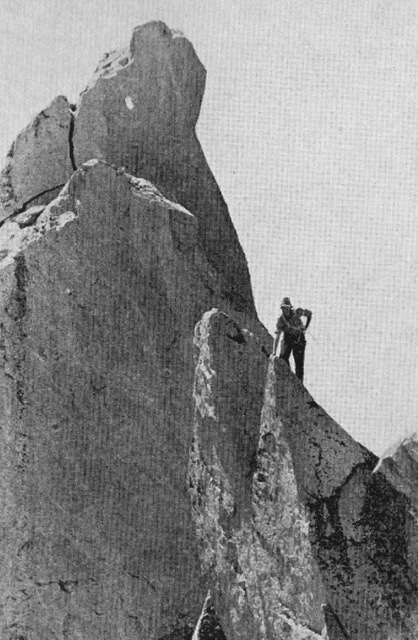

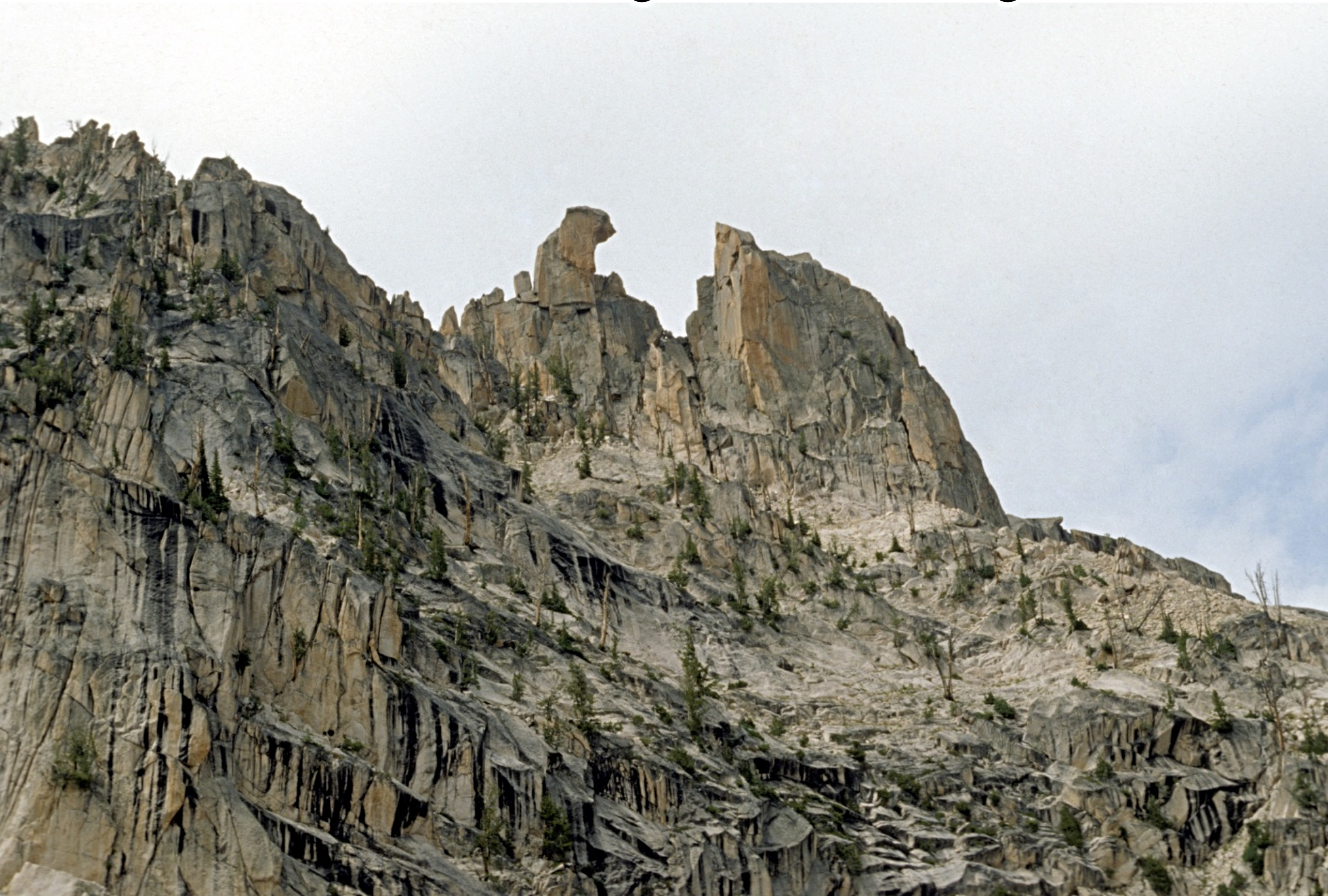

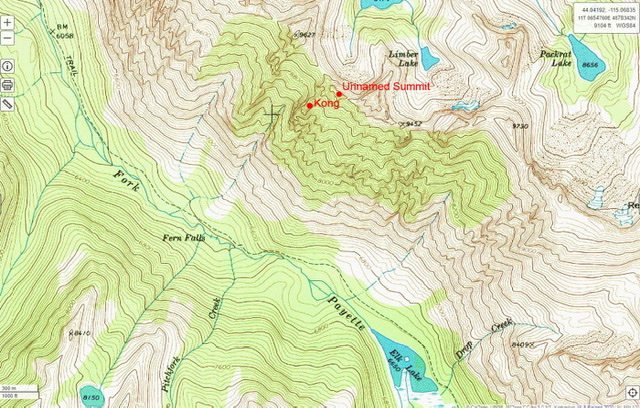

Our trip was one year after I had started rock climbing, and because we had pack mules to haul our loads on this trip, I had decided to take my rock gear along. I also kept an eye out for opportunities for future trips and wasn’t disappointed once we passed Fern Falls on the South Fork of the Payette River. As we rode farther up the trail, I gawked at the granite formations on the east side of the valley and thought, “Wow.” One formation in particular stood out. I shot photos and vowed to come back to it with my rock-climbing buddies. The first name for it that occurred to me was King Kong, which stuck, although we later shortened it to Kong.

After a long day in the saddle, we arrived at Ardeth Lake. Our outfitters had previously set up wall tents, so it was kind of like arriving at a motel in the wilderness. The pack mules had ensured there was just about nothing that didn’t get packed, including a couple of coolers full of drinks and comfort food like steaks and burgers. I wasn’t used to this kind of backcountry camping but quickly adapted after being offered an ice-cold beer. The early fall weather had been perfect for the ride up to camp but the next morning we woke to the surprise that it had snowed a couple of inches overnight.

Typically for fall, the weather improved by evening and the next day promised to be much better. The morning was clear and cold but by afternoon it had warmed into the lows seventies , and the dusting of snow had all but melted. The Carson kids, Bruce, Jackie, and Guy, headed up Tenlake Trail with me, and after about a half-mile we spotted a worthy climbing objective: the eastern face of Point 8590.

It was getting late in the afternoon so we went back to camp, our plans for the next day now set. After a big breakfast along with real cowboy coffee, in which the grounds are dumped right into the water and boiled over an open campfire, the four of us headed back up Tenlake Trail, this time loaded with rock-climbing gear and a rope. We found a series of ledges that started out as second class but turned to fourth class higher up the face. At that point, Jackie decided she had had enough rock-climbing and went back down. Bruce, Guy, and I continued up until we finally reached a point where a rope and belay were in order. I led the first pitch, a delightful 5.4 (of a maximum 5.15 class rating) on near-perfect granite. After I brought Bruce and Guy up, we stayed roped and finished with another pitch of fun climbing. Below the top it turned to easier ground where we could scramble to the high point on the ridge and soak in views of the central Sawtooth Range.

As soon as I got home from our pack trip, I started talking up with my climbing friends what I had seen on the Payette River. It didn’t take long to generate interest in Kong, and we made the trip in early October. This time we didn’t have horses, which meant our backs and legs took the load on the grueling hike above Fern Falls. After a hard day on the trail, we found a nice camping spot below our objective and spent the night. The next day we started looking for a way to get up the rock to the bottom of a massive slab that marked the beginning of final peak. There was an obvious gulley along the left of the climb but it was very steep, loose, and it looked like a death trap loaded with boulders that could tumble in a heartbeat. We found a fourth-class zigzagging rock route that led to a nice ledge (for camping or bivouacking) close to the base of the slab, but it also was out of the question, because we’d be carrying full climbing packs. It was getting late and we knew we’d have to do more exploring to figure out this challenge. We descended and decided to come back early the next summer, when the gulley would most likely be filled with snow.

Not wanting to leave without some kind of summit, we decided to explore the top of the ridge and try to find the finish of our future climb. We were carrying only day packs, so we climbed up the gulley and along the ridge, where we spotted some interesting formations. There was a beautiful tower at the top of the gulley and we gave it a try. Mike made it all the way up to the last thirty feet, where the rock went blank. Lacking bolts or any way to protect ourselves, we called this one a near miss. Following the ridge that separates the Payette River and the Goat Creek drainages, we spotted a summit that looked reasonable and got to the top of it.

When the time came in June 1974, we decided to do things a little differently. Instead of hiking up the South Fork of the Payette River and arriving in the heat of the afternoon, we would spent a night at the Grandjean campground and depart at 1:00 a.m., which should put us at our base camp early in the morning. Everything went as expected and we arrived in time for breakfast and a good rest. We lounged around for most of the day, enjoying the scenery and exploring the Elk Lake area.

The weather was perfect and mosquitoes were non-existent, so we camped without bothering to put up a tent. Early the next morning, I awoke to the sound of something shuffling around our camp. I raised my head to the sight of a medium-sized black bear sniffing the foot of our sleeping bags. I sat up in and yelled to the guys, who woke all at once. My thought was that once the bear saw us, he’d bolt into the woods. Instead he slowly walked past us and stood on his hind legs to show us how big he was. A few minutes later, he took off into the brush and we didn’t see him again for the rest of the morning. We weren’t too worried about him, because we had plans to head up to our bivalve ledge for the day so we loaded up our climbing packs and headed up the gulley. We had brought ice axes but no crampons, figuring the snow would soften up a bit by the time we got up the gulley. We were wrong.

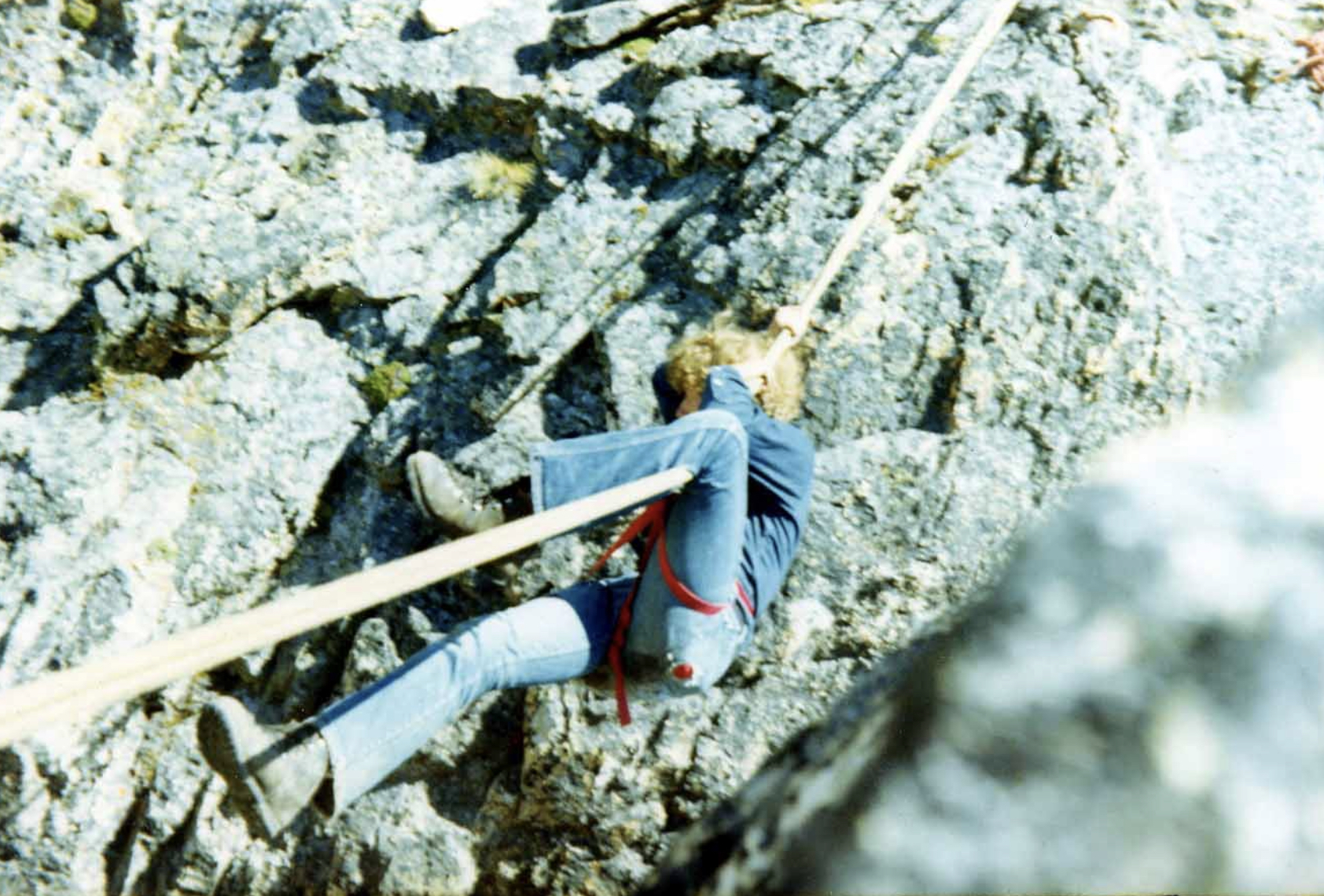

The gully was reasonably accessible, but we could see that a short climb up an incline of fifty-five-to-sixty degrees on hard snow to the biv site would require step-cutting and a lot of “pucker factor.” After reaching the bivy ledge we scrambled up to the start of the climb where Guy and Carl watched while Mike and I racked up and tried to find a continuous crack system up the face. We finally spotted a good-looking line and I led the first pitch. I led up maybe ninety feet to the bottom of an overhanging, left-leaning fist crack that flared into an arm-and-knee crack. I didn’t think I could free-climb it so I slapped in a couple of hexes (hexagonal nuts that can be placed without a hammer) and pulled out my aiders (short ladder slings). Once I rounded the lip, I went free, but it was still very awkward and hard. I made it over the edge and decided to set a belay (a pulley-like device to control the rope)so I could talk to Mike when he came up. He ascended to the start of the overhang and then decided to try free-climbing the rest of the way up. After a fair amount of swearing, grunting and sweating, he made it over the lip. We really didn’t know grading very well but we both thought that it was maybe a 5.10. It later proved to be the crux pitch of the climb. We went up another pitch to a ledge system along the crack, and the climbing was still fairly stiff. We had burned up quite a bit of time getting to the base and working out the first two pitches so we knew we had to make a decision. It was getting late in the afternoon and we still had to descend the gully to get back to our base camp so we rappelled off and decided to come back the next summer to try it again.

After descending the gulley we hiked back to where our packs were stashed and discovered that our bear friend had made another visit. All our packs were untouched except for Guy’s. It was missing two of the outside pockets that had had food in them and his foam pad had a large bite taken out of it. It was rolled up and when he unrolled it, it reminded me of how we used to make paper dolls. He accused the bear of being out to get him and no-one else. We picked up our packs and headed back to our base camp. As we ate the last of our food and listened to Guy grumble about the bear, Carl came up with an idea for revenge. He had part of a loaf of bread, some honey and a tin of cayenne pepper, so he and I went into the brush to fix the bear a snack.

We found a stump and Carl stacked bread as if they were pancakes. In between each layer of bread he dumped a couple of tablespoons of cayenne pepper and then topped it off with a generous helping of honey. Chuckling, we headed back to camp. Figuring the bear wouldn’t find the bread for a while, we sat around talking about our adventure. We were wrong again. It took the bear only about thirty minutes to discover his snack, and he was very annoyed. As he came out of the brush above our camp, he was ripping leaves off the bushes. We could see he had a mouthful of leaves and the hair on his back stood up. He snorted around and wouldn’t leave, which made us nervous, so we decided to use the African bush-beating method we’d seen on TV to chase him off. We all picked up our ice axes and at the word “go,” we charged toward him. We got about halfway to where he was sitting when he reared up on his hind legs and charged us. We turned and ran as fast as we could back to our camp. Luckily, his charge was a bluff, but he would not let us out of his sight. We agreed that maybe it wasn’t a good idea to stay there for the night. Under the watchful glare of the bear, we packed and hiked back to Grandjean.

On our third trip at the beginning of July, 1975 we altered our plans once again. Instead of camping at the base and climbing the gully, we decided to haul all of our gear up to the bivy ledge both saving us time and avoiding any more encounters with our buddy, the bear. We couldn’t convince Guy to go back again so we recruited Mike’s cousin Sam to join us on our adventure. Carl was still interested so as a foursome we headed back up to Grandjean for the long grind up the Payette River. After a long day on the trail and a hard climb up the gully, we made it to our bivy spot below our climb.

Early the next morning, Mike took the first lead up to the crux overhang. I had set a directional belay about twenty feet from the start in order to be able to watch him climb. Just as he was grunting his way over the bulge, he suddenly flew out of the crack and I heard him yell “falling.” As I was pulling in slack, his top piece of protection popped out and then my directional anchor gave way, leaving maybe thirty feet of slack in the rope. I watched him free-fall around forty feet until he came to a stop about thirty feet off the deck. As I lowered him, he cursed about having almost made it. I thought he’d pass me the lead after recovering but that’s not how Mike works. He quickly gathered himself and went right back up, more determined than ever. On this second try, he cracked the code of the crux and continued up to a nice belay ledge.

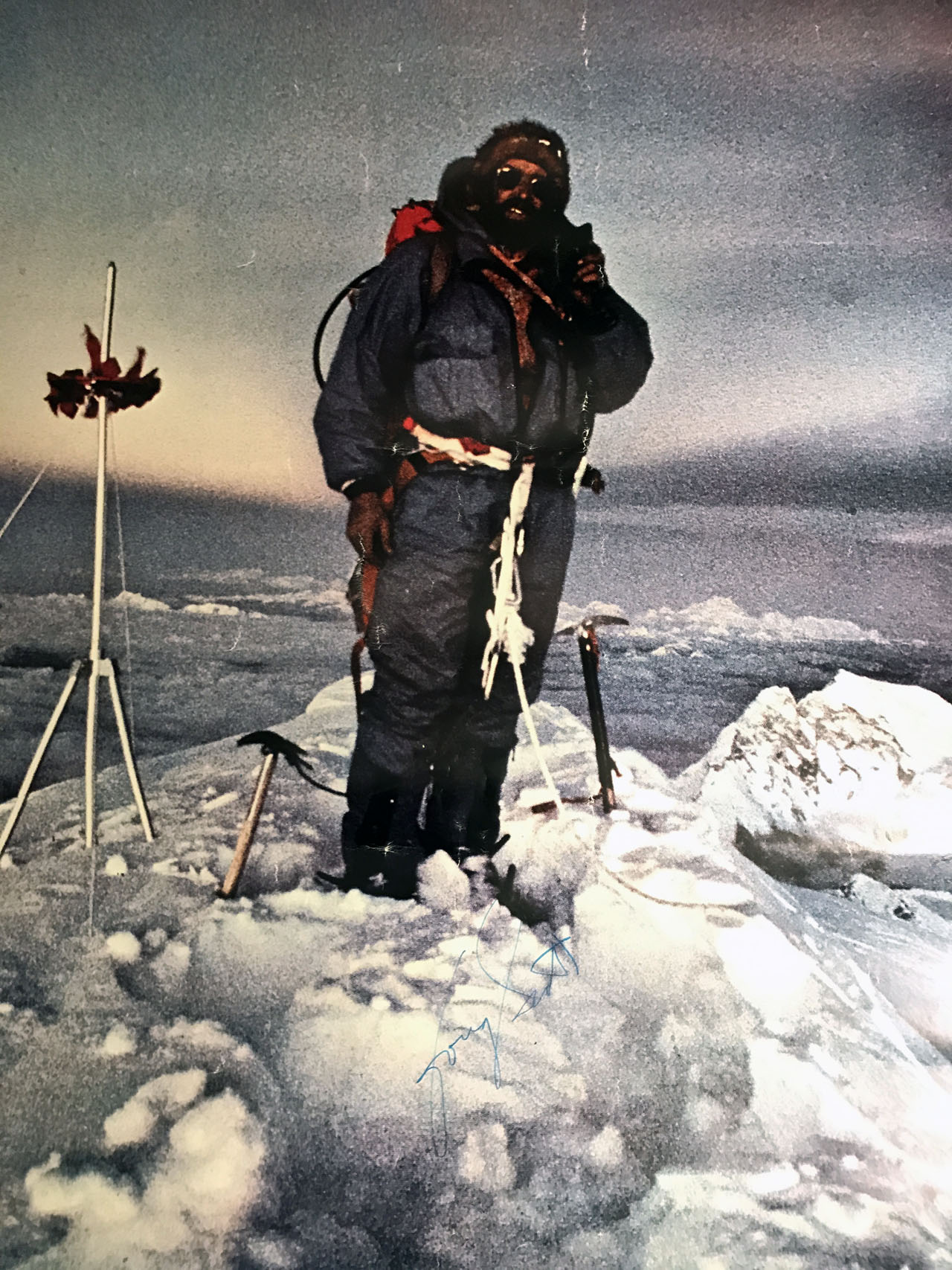

The next pitch led up to a dihedral (two planes of intersecting rock face). The climbing was on near-perfect granite that varied from hand-width to arm-width cracks. I led pitch three, which ended on a nice flat ledge midway up the dihedral. Mike took the fourth pitch, to the top of the dihedral, where we stopped to inspect the final short pitch to the top. There was no defined summit and from our ledge, we saw only two options for what we called the “H” pitch. To our left was a thirty-foot horizontal knife-blade crack that would require aid and led to places unknown. To our right was a large overhanging flared crack that would require very large pieces of gear to protect us. We didn’t have the right equipment for either approach, so we were stuck concerning how to finish the last fifty feet of rock. Bolts would have worked but we were devoted to the clean-climbing ethics of the time and neither of us owned that kind of hardware. We talked about cutting tree limbs for chocks and slinging them with webbing but it was too late in the day for that, so we called our high point good and began to rappel back down to our start.

The first rappel went a without hitch and we had only to leave a single sling behind on our way down. On the third rappel, things were looking good until I pulled the rope down. Just after the free end started to fall, it stopped. We pulled as hard as we could and realized it was jammed hard and would not budge. It was late in the day and clouds were building rapidly in the west. Ascending a stuck rope was completely out of the question and neither one of us wanted to lead that pitch again. We had two ropes with us, so along with the shortened end of the stuck rope, we still had enough rope to get down. I free-climbed up as high as I could without aids and cut the rope, after which we descended to our bivy ledge for another night but soon discovered our adventure wasn’t over yet.

By the time the four of us down-climbed to our bivy ledge the sun was starting to set. We ate and settled into our respective spots. Soon it got dark and the wind began to blow in earnest. We saw the first of many flashes as a thunderstorm rolled in from the west. Rain poured down and the wind whipped up to about 50 m.p.h. We huddled in our spots and, in case we took a hit, we said goodbye to each other over the howling wind. Lightning struck below and above us. Rain hit the rocks in sheets and for maybe ten minutes it went up the mountain instead of down it. It then changed direction and poured downward for at least another half-hour. Lightning flashes that illuminated the entire mountainside left us temporarily blinded. There was no pause between the lightning and thunder, only loud explosions and an acrid smell in the air. Finally, the storm passed, and we were all okay. I later realized we had gone through a vertical wind shear, where the wind blows up one side of a thundercloud and down the other. We had experienced both sides of the storm.

As chance would have it, it was the evening of July 4. In the morning, we not only were a little shaken from the excitement of the night before but realized we needed to rethink our hardware. We down-climbed and went back to Boise, where we read that a hiker had been killed by the same storm on the eastern side of the range.

We always intended to go back and finish that last little bit of climbing to the top of Kong and retrieve the piece of stuck rope we had left hanging, but we were distracted by other Sawtooth climbs, such as the Finger of Fate and Elephant’s Perch. Around that time, we also started making regular trips to the Tetons and North Cascades. For us, Kong turned out to be the summit that got away.