“Rugged country. Awful rugged country. Miles and miles of sharp jagged pinnacles of firm granite.” A painter-friend of Bob Underhill told him that about Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains in the early 1930s, when Bob was in the Tetons for a few weeks pioneering big new routes on the Grand Teton and other nearby peaks. Although the painter isn’t named, it almost certainly was Idaho native Archie Teater, who had hiked the Sawtooth mountains for weeks with a pack burro, painting and prospecting for gold. Archie started spending summers at Jenny Lake at the base of the Tetons in 1929, painting pictures of the mountains and selling his paintings to tourists. Archie Teater’s campmates at Jenny Lake included early Teton climbers Glenn Exum and Paul Petzoldt.

Bob Underhill and his climber-wife Miriam were interested. What they discovered, by researching climbing club journals, was that the Sawtooth Mountains were unknown to the climbing world. Their subsequent adventures in the Sawtooths captivated me, as a climber who has summited many of the peaks that the Underhills were the first to conquer in the 1930s. I found the couple’s writings on their Sawtooth adventures captivating.

Miriam Underhill’s article on their 1934 trip, titled “Leading a Cat by Its Tail,” was in the December 1934 edition of Appalachia magazine. Robert Underhill wrote a summary of both their trips into the Sawtooths, aptly title “The Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho,” for the December 1937 issue of Appalachia Magazine and Miriam writes about both their Sawtooth adventures in Chapter 9 of her 1956 climbing autobiography “Give Me The Hills.”

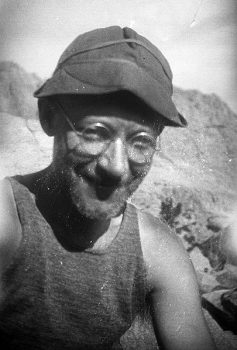

They were each uniquely qualified to climb difficult, unexplored, and unclimbed peaks. Both were from upper middle-class families and both had much experience climbing difficult peaks in the Alps. They had met during Appalachian Mountain Club trips to mountains in New Hampshire but, for the most part, climbed separately in the Alps. Miriam’s access to wide areas of the Alps, in France, Switzerland, and Italy’s Dolomite Mountains was enhanced by a Buick touring car her parents shipped over to France for her use. By the late 1920s, both Miriam and Bob Underhill had established reputations as some of the best climbers in the world and they had started occasionally climbing together in the Alps by 1928.

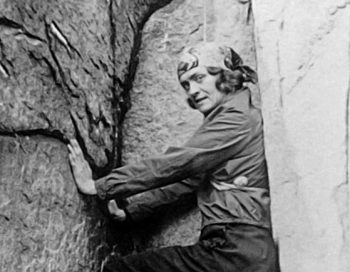

As Miriam gained climbing experience, she suffered, first with alpine guides who would never let a woman lead, then after she started leading more difficult climbs with more tolerant guides, by the attitudes of the time, that women were too “frail” to be trusted as an equal climbing partner. She started climbing with like-minded women and did some very difficult climbs. In the 1920s, climbers tied themselves together with hemp ropes, but leaders led without driving pitons into cracks to “protect” themselves if they fell. The rule was “the leader must not fall” and Miriam led some very hard climbs without falling including a “test-piece” that only a few Chamonix guides would lead, the famed Mummery Crack (currently rated as a French 5b, or 5.8 – 5.9 by U.S. difficulty ratings) on the Grepon. A photo essay and her article about what she and her friends termed “Manless Climbing” was published in the August 1934 issue of National Geographic Magazine, two years after she married Bob Underhill, and suddenly they were not only the best, but the best-known climbers in America. Bob Underhill was not as famous, but in addition to his new routes in the Tetons, he wrote a 22-page article “On the Use and Management of the Rope in Rock Work,” which was published in the Sierra Club Bulletin in 1931. He then taught modern rope techniques to Sierra Club members in California and did two big first ascents in the Sierra with his best students. The Robert and Miriam Underhill Award is given annually by the American Alpine Club “to a person who, in the opinion of the selection committee, has demonstrated the highest level of skill in the mountaineering arts and who, through the application of this skill, courage, and perseverance, has achieved outstanding success in the various fields of mountaineering endeavor.”

In June of 1934, the Underhills made the long drive from Boston to Idaho and first stopped in Hailey at the Sawtooth National Forest headquarters to inquire about available horse packers for their Sawtooth adventures (Hailey does not now have an active ranger station). They were referred to a prosperous Sawtooth Valley rancher named Dave Williams and after explaining their needs to him, Dave jumped at the opportunity to share in their adventure. In fact, they could start the following afternoon. Miriam explained: “In the morning he’d have to round up and shoe us some horses, of which he owned large numbers; he wasn’t sure how many, since he hadn’t caught them all that Spring.” Dave had gone to the “school of hard knocks” and had first worked in the area carrying mail twice a week over 8,750-foot Galena Summit from Ketchum to Stanley. The road was closed by snow for six months a year and then Dave rode a horse, or drove a dog team, or wore skis, to make the 61-mile journey. The Sawtooth Valley was mostly ranched by folks on small “starvation-ranches,” but Dave had managed to prosper, supplementing his income from cattle ranching with income from leading pack trips into nearby mountains for fishing or hunting.

The next afternoon at 4:00 P.M., the three started for the mountains with three riding horses, two pack horses, and one of the pack horses an unweaned colt. Dave led the better-trained pack horse, but “Diamond, the other and a most ornery beast, was left to run loose and it was up to Bob to see that she came along.” After Dave warned Miriam that her horse would buck if brush or clothing touched its rear, she also got to avoid the colt, who would dash in front of the other horses and practice bucking. Miriam wrote, “I felt sure that when he grew up to be a big horse, he too would be a splendid bucker.”

Somehow, they made it up the barely discernable Hell Roaring Creek Trail to Imogene Lake by dusk and camped for the night. Dave led the belled horses to a pasture at a small lake above camp and warned the Underhills to be alert for the horses trying to sneak past them in the night, to return to his ranch. Nothing bad happened in the night and the next morning Dave and the Underhills hiked up to round up the horses. “Searching for the horses, we hiked up a turbulent little stream, Bob on its right bank and Dave and I on its left. The horses appeared on Bob’s side. Dave shouted across the stream that Diamond would be the only one likely to let Bob get up on her. Bob was to mount Diamond and drive the others across the stream. No one would have guessed that as Bob swung up on that big, round, slippery horse, unsaddled and unbridled, that he was doing this for the first time. But from then on, things went less well. ‘Just go after them like you was roundin’ up some cattle, Dave instructed.’“

“Bob’s primary difficulty lay in steering Diamond, but even when he managed that, and charged up to the other horses, they continued their placid grazing in complete indifference. An expression of increasing amazement grew on Dave’s face as he watched the ineptness of this eastern dude. ‘It’s a funny thing, he observed to me, but I guess there’s something to learn about most anything.’ In the end, Dave had to wade the stream and do the job himself.“

Later that day, they went over a high pass just south of Imogene Lake and in a thunderstorm, worked through scenic, but trail-less, steep and rough country to Toxaway Lake, where they camped for three nights. Miriam mentions one of the more exciting parts of their descent. “We all walked most of the most of the way, sloshing along in oilskins. At one point, Diamond, who always knew better than the other horses, or even Dave himself, what route to take, started down a sloping slab of rock which the rest of us had skirted. She fell at once and slid – a sitting glissade. Noticing that my horse was then in line at the bottom of the slab and that I was slightly below it, I expected momentarily to be covered up by two horses. But although Diamond did slide into him, he stood his ground.”

At the bottom of the mountain, they found a trail that came up from Yellowbelly Lake and followed it to Toxaway. Three lads from Salt Lake City were fishing there and during the ensuing conversation they expressed wonderment that anyone would come into the Sawtooths just to climb. Subsequently, the Underhills learned that Dave had often carried containers with live trout up to fishless Sawtooth Lakes so he could later make money hauling people up to those lakes to catch trout.

The next day, they climbed Snowyside Peak (10,651 feet), one of the tallest Sawtooth Peaks. It had been climbed previously by USGS map-makers on a survey of the Sawtooths and was the only peak the Underhills and Dave ascended that Summer that was not a first ascent. I climbed Snowyside’s east ridge in 1971, which is likely the route the Underhills and Dave Williams took up the peak.

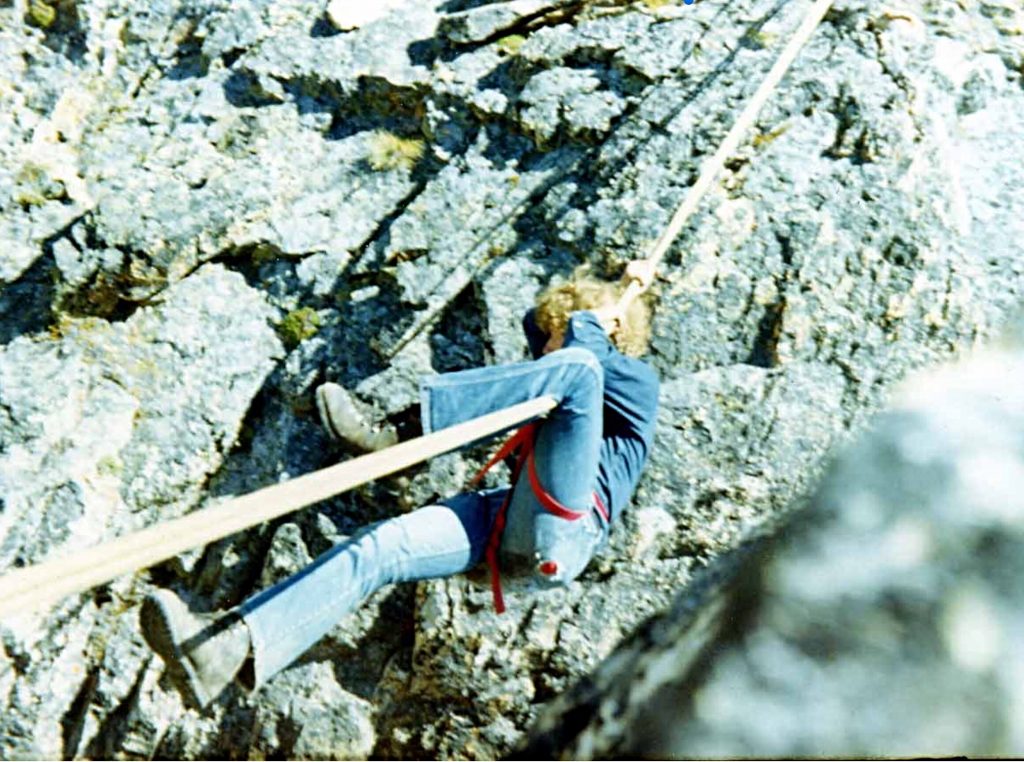

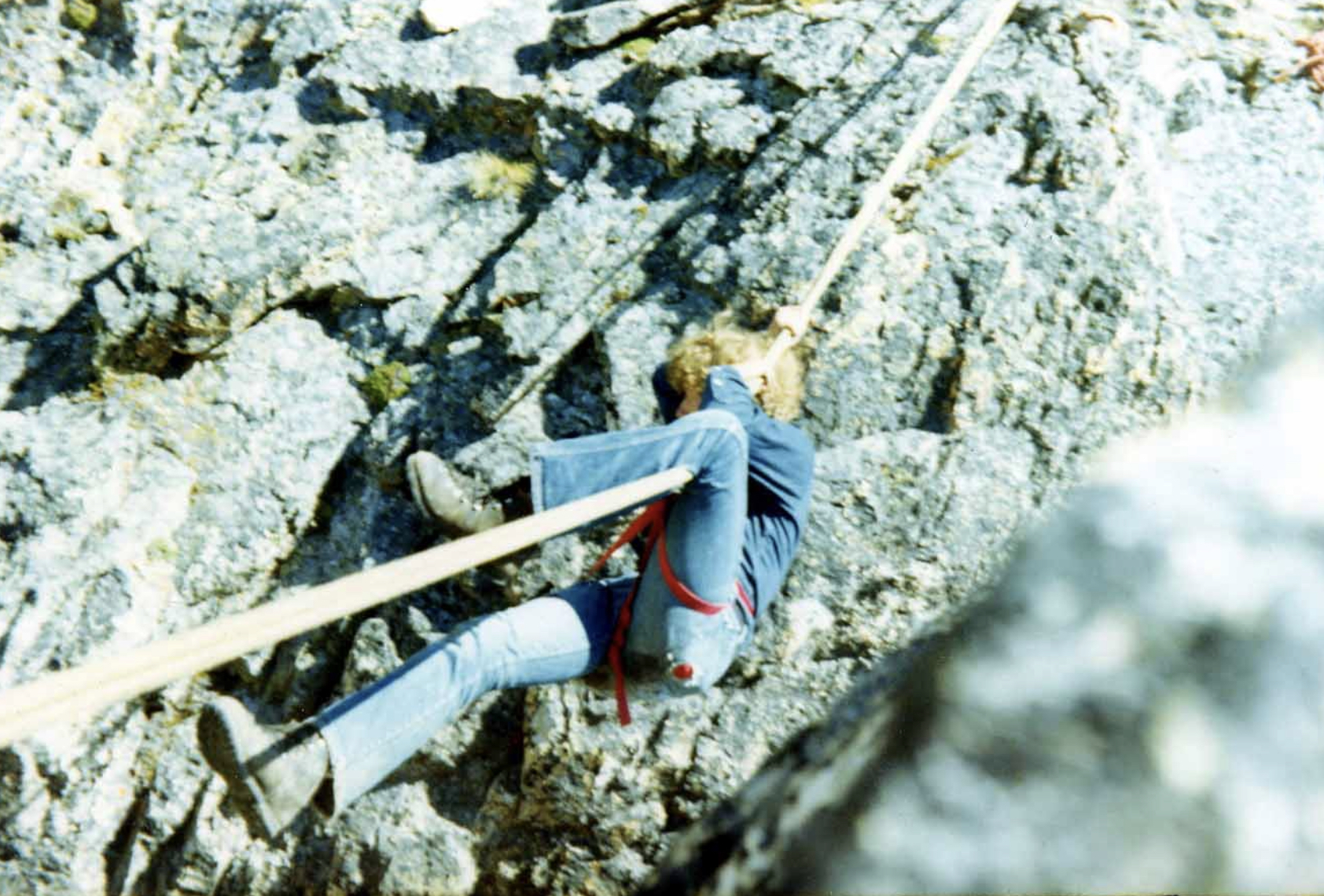

Dave was athletic and had spent a lot of time in the mountains hunting goats. He wanted to climb with the vastly more-experienced Underhills and did a great job, although he did not trust their ropes. On their descent from a ridge extending north from Snowyside, they needed to do several rappels to descend a steep part about 200 feet high. Miriam writes: “How uneasy Dave felt! Those thin little ropes did not look like they could hold him. To reassure himself, before starting, he peered over the edge to the valley below and observed if worse came to worst, he could make it in about two jumps.”

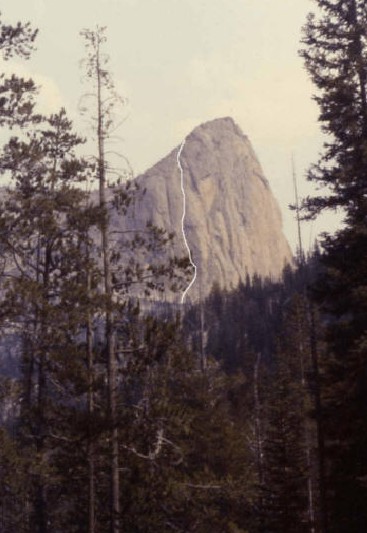

From the top of Snowyside, they noted, far to the northwest, what they called “The Red Finger,” now named The North Raker. They found it so striking that they wanted to go there, even though Dave thought the South Fork Payette River Valley between them and it did not have a trail. However, he knew a pass he could get his horses over and he was willing to try to get them to the North Raker.

The next day, they went south and climbed an imposing peak above Alice Lake, later named El Capitan, finding a route up its east side that was not entirely satisfactory, due to much loose rock. The peak was unclimbed and Dave, with his usual enthusiasm, built a huge summit cairn.

The following day, they bushwhacked over Dave’s pass into the upper South Fork Payette Basin. They went over a trail-less low pass west of Toxaway Lake to Vernon Lake. Then they had to follow twisty elk trails at a slow pace for miles down the South Fork Payette Valley until they were almost to where they would need to cross the river to go up to the Rakers. At that point, they intersected a beautiful, newly-cleared Forest Service trail which they had likely been next to for several miles. One-half mile above Elk Lake, they camped in a meadow and the next day Bob and Dave hiked about 3,700 vertical feet up steep slopes to the east and made a first ascent of another big mountain, Elk Peak (10,582 feet). I had an easier time of it in 1971 when Harry Bowron and I camped in the Upper Redfish Lakes basin at about 8,700 feet, northeast of Elk Peak, and the next day chased a mountain goat up the north ridge of Elk Peak. Although Bob and Dave are credited with having climbed the east ridge, we all most likely hiked the north ridge which is an obvious route and the first one they would have come to.

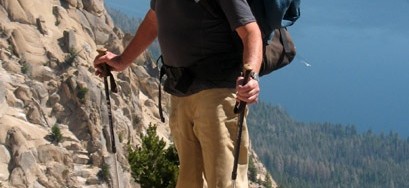

From the top of Elk Peak, Bob and Dave were able to clearly see the least difficult way to access the Rakers, which was up aptly named Fall Creek, just above their camp. Dave did not believe he could take his horses up there so they first planned to go up with minimal overnight gear, bivouac just below the Rakers, and climb the next day. During a rest day, they ended up deciding to do the trip in one day with an early-morning start. The first obstacle the next morning, was the deep and fast-flowing South Fork Payette. Dave solved the problem by cutting down a tree for a bridge with an axe he just happened to be carrying. It took them about 3-1/2 hours to make the hike up to the north side of the Rakers. I went up the same way in 2009 with my wife Dorita and our fit friends Jerry and Angie Richardson, but we backpacked all our camping gear up the trail-less, steep, and brushy lower part of Fall Creek. From there, we followed game trails up more open terrain to the Rakers.

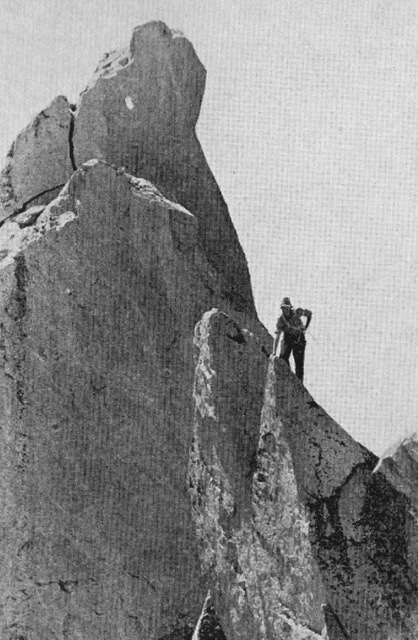

The Underhills and Dave were able to scramble nearly to the top of the North Raker, but were defeated by a steep, holdless, and rotten tower that was its southern high point. However, they were able to do a first ascent on the smaller South Raker as well as some much smaller summits between them.

Dave and the Underhills were able to go up to the Rakers, have their climbing adventure, and make it back to their camp on the South Fork Payette in one long day. In 2009, we hiked around the Rakers and spent another day exploring peaks on the east side of Fall Creek. Unfortunately, when we went back down to the South Fork Payette, we ended up descending steep terrain a little ways down-river from where we had gone up. We discovered a bottomless side-channel, but we were able to cross by breaking a floating Spruce log loose from our side, which Jerry pulled and I pushed to make a floating bridge.

The food box Dave and the Underhills had packed for eight days was nearly empty, but they decided to stretch their food and go down the South Fork Payette Trail to Grandjean, then up Trail Creek to near 10,190-foot Mount Regan and climb it before going out to Stanley Lake and roads. They discovered Trail Creek was badly named and they had more adventures getting their horses up it. After camping west of Mount Regan, they tried to climb Mount Regan by the northwest ridge the next day, but were defeated on their first attempt by what Miriam describes as a 20-foot wide gap. They had to go back down, circle the mountain, and make a first ascent of it by the southeast ridge.

I climbed Mount Regan via the northwest ridge in August of 1970 with three friends. It was my first Sawtooth peak and all we knew about it was that it had been climbed. We found it on a Forest Service map, hiked up a good trail to Sawtooth Lake and camped under the east side of Mount Regan. During the evening, we agreed on a likely route and the next morning, we scrambled up the peak. We had a 120-foot Goldline rope and some climbing gear with us and our best climber, Harry Bowron, did a little engineering to rig our rope across the gap that stopped the Underhills and Dave, so the rest of us could slide across the rope in what’s now called a “Tyrolean Traverse.” I was somewhat surprised to learn a few years back, that minor obstacle had stopped the Underhills. What is more interesting is Bob Underhill posted this footnote to their climb in his 1938 article on their Sawtooth adventures in Appalachia Magazine. “Nor do I think it could be crossed by a rope traverse at least at any point we investigated.”

The Underhills and Dave Williams were from very different backgrounds, but they had shared a grand 10-day adventure and were now lifelong friends. Before they parted, they were already planning another pack trip to explore the peaks of the Sawtooth Mountains. Bob Underhill was employed as a Harvard instructor, first in Mathematics, then he became a philosophy professor there and perhaps those responsibilities led to him and Miriam not being able to visit the area again until early September 1935.

Dave Williams met them at the Shoshone train station, 118 miles south of Stanley. This year, they only had a 3-week break from responsibilities and had journeyed by train to Idaho from Boston. Dave had plans to pack along a larger tent and a camp stove he carried when packing hunting parties, to deal with cold Fall nights in the mountains. Miriam noted one of Dave’s lighthearted remarks on the drive from Shoshone to his ranch. “I can’t understand you Bob, he observed thoughtfully. In my experience there’s just two reasons for a man to go off into the woods. One is to get away from his wife and the other is to get drunk. But you bring your wife with you and you don’t bring no whiskey.”

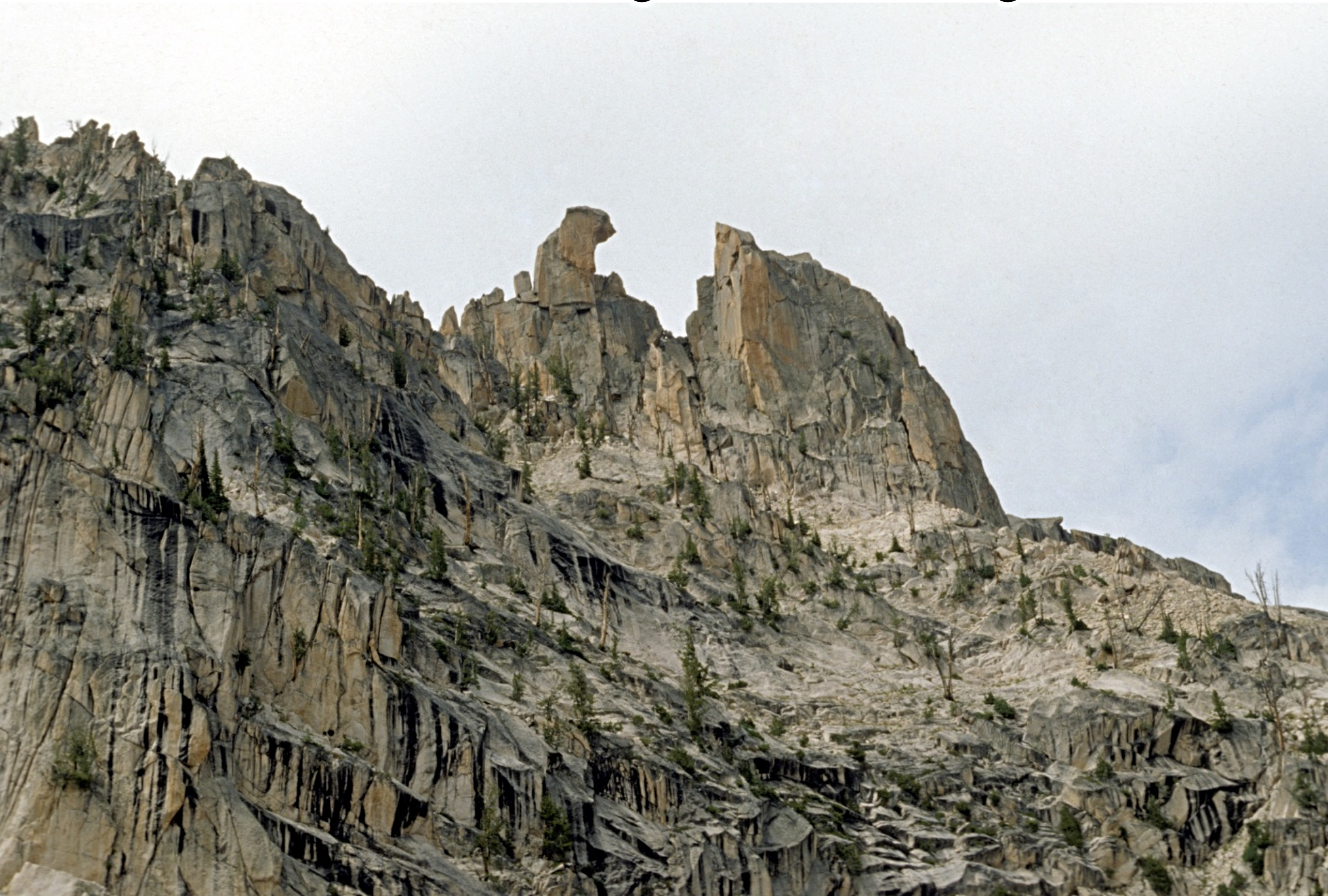

The first 1935 trip objective was Mount Heyburn just west of Redfish Lake. The Underhills and Dave Williams went up the long decomposing granite slopes on the south side of Mount Heyburn from Redfish Lake Creek and after exploring three of Heyburn’s possible high points, succeeded in making a first ascent of the highest summit via the 5.6-difficulty Southwest Ridge Route. Bob was moved to describe the crumbly granite on the ridge: “The smooth gables and humps which formed the crest of the ridge were surfaced with a gravelly material that crumbled off like well-caked mud.” Later Sawtooth climbers would describe the southern slopes of Mount Heyburn as being composed of “ball-bearing granite.”

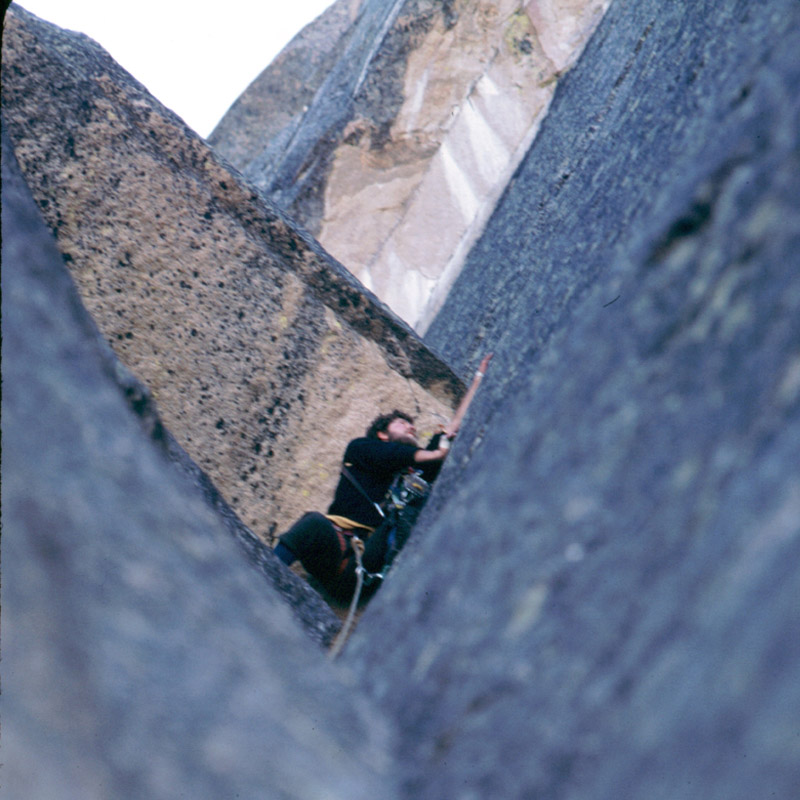

During the two days they spent exploring Mt. Heyburn’s rotten rock, Bob was also most impressed with what were later named the Black and Grand Aiguilles, located in a small cirque adjacent to and just southwest of Heyburn.

Bob wrote that they were genuine Chamonix-type aiguilles that would provide magnificent ascents if they could be climbed without artificial aids. That conclusion was reached after they made attempts on each summit. These aiguilles and others nearby, were later considered major Sawtooth challenges and most of them were climbed in the 1940s by routes not considered difficult by modern standards. I never visited them until my wife Dorita and I hiked up to the Grand Aiguille in 2011 with a light rack of climbing gear and a 9mm rope, expecting to “knock-off” the 5.4 route it was first climbed by in 1946. When I got up close to the Grand Aiguille, I was suddenly just as impressed with it as Bob Underhill was in 1934. I simply could not see an easy route up it and notes from the 1946 first ascent mentioning “The third pitch leads to some large granite flakes out on the face. (These flakes are shaky when pulled outward, but are secure when downward pressure is placed directly on them.)” were worrisome to me. I found myself wondering just how shaky those flakes now were, 66 years after the first ascent. It was a nice scenic cirque and Dorita and I spent the rest of the afternoon exploring it and enjoying the views after I gave up on the climb.

From their camp below Mount Heyburn, Dave’s horses carried them up Redfish Lake Creek to another camp spot. They spent two days exploring peaks to the northwest and made a first ascent of another of the highest and most scenic peaks in the range, Packrat Peak (10,240 feet). Bob mentions an attempt on another peak bordering Redfish Lake Creek which they could not complete, since they had neglected to bring a rope and Miriam mentions achieving other ascents “up Redfish Creek.” Although I can’t find any specific mention in the Underhill’s Sawtooth stories, they are also credited with a first ascent of the next peak south of Packrat. The 10,160-foot peak is now named Mount Underhill in their honor. Both Bob and Miriam stayed discretely silent about the many unclimbed sharp and technical summits just north of Packrat Peak. Perhaps they planned on another Sawtooth trip that never happened?

Then Dave and the Underhills traveled back down to Redfish Lake and up Fishhook Creek, the other main tributary stream of Redfish Lake, and camped. From there, they made the first recorded ascent of the highest of the Sawtooth Mountains, 10,751-foot Thompson Peak. It is difficult for me to follow Bob’s description of how they approached and climbed Thompson, so I won’t attempt to share it. Dave and the Underhills also hiked 0.8 mile north from the summit of Thompson and made the first ascent of what is now named Williams Peak in honor of Dave Williams. Thompson was the second Sawtooth peak I climbed in June 1971 with my friends Harry Bowron and Gordon Williams, and we managed a summit group portrait.

That was it for the Underhills in the Sawtooth Range. On their 1935 visit, they also made the second ascent of nearby 11,815-foot Castle Peak in the White Cloud Mountains. However, their visits were noted by Idaho’s largest newspaper in two articles and their Appalachia Magazine articles were noted by other U.S. climbers. They had “opened up the range” and other climbers would slowly follow them after the Great Depression and WWII ended.

With that future in mind, Bob also wrote some notes on the Sawtooth Mountains in his 1937 Appalachia article aptly titled “The Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho.” “The major Sawtooth peaks are between 10,000 and 11,000 feet high. The mountain valleys from which those peaks rise immediately may be situated anywhere from 8,000 to 9,000 feet. In point of elevation, therefore the climbs generally amount to very little. Furthermore, it may as well be confessed at once that on the average they are not difficult…”

“Much of the climbing pleasure the Sawtooth region can afford is therefore reserved exclusively for its first explorer, for whom everything has at least the fascination of being unknown and problematic. Nevertheless, I think there is quite a lot here to engage the interest of the rock climber as such – though to be sure he should be a rock climber who is willing for the moment to turn aside from long expeditions to shorter days spent largely in the lighter exercise of his craft—and preferably one who is content to accept as part of his reward the great charm of the country and of the camp life it permits…”

Bob Underhill’s thoughts led to a strong local climber ethic about the Sawtooths that my friends and I embraced when we started climbing there in the early 1970s. Simply stated, it was “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” We all knew the fun in the Sawtooth Mountain lay in the adventure and too much knowledge of the area ruined the adventure.

Jumping forward to 2020, it is increasingly more difficult to maintain the adventure, for those who want to discover their own new valleys, new peaks, and new routes in the Sawtooth Mountains. I realize many younger climbers crave “beta” (information and details) on routes, like we used to crave adventure. However, folks can climb in other mountain ranges and enjoy exact details on approaches, peaks, and routes. In the Sawtooths, it is still a lot of fun to just go in, pick out a peak, and attempt to climb it.

Try it, you might like it.

My thanks to Christine Woodside and Becky Fullerton at Appalachia Magazine for their assistance with sharing Miriam Underhill’s 1934 article, and to Tom Lopez, author of Idaho A Climbing Guide for his assistance.

Ray Brooks. Copyright March 5, 2020