The Summer of 1949: Fred Beckey, Pete Schoening and Jack Schwabland went into Idaho’s Sawtooth Range to finish “some business” with two peaks that had repulsed their climbing attempts the previous Summer. They also had a shopping list of other unclimbed peaks in the Sawtooths. Their “Idaho adventure” may well be the most exciting epic in Idaho’s climbing history.

Fred Beckey passed away at age 94 in 2017, after becoming a “living legend” in climbing circles as the man who had done the most first ascents and new routes in North America. Pete Schoening is most famous for saving 5 of his team-mates when they fell on K-2 during a 1953 expedition. Pete was also part of the group that made the first ascent of Gasherbrum I in 1958, the only 8,000 meter peak first climbed by Americans. Jack Schwabland was a highly respected climber who took part in many first ascents in the Northwest.

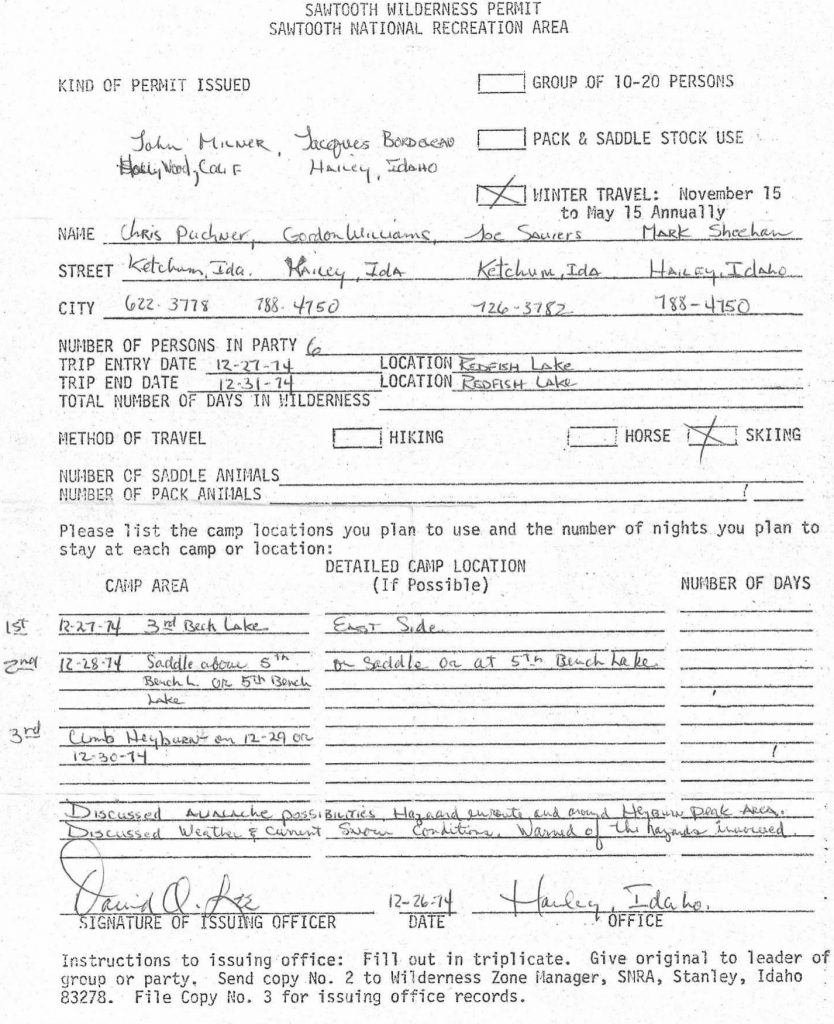

The only write-up I have been able to find of their Sawtooth adventures is an photo-less article by Jack Schwabland in the 1950 American Alpine Journal: “Sixth-Class Climbing in the Sawtooth Range.” To chronicle their “Big Sawtooth Adventure,” I will include extracts from that article along with my own photos and experiences on these peaks.

Their “shopping list” for the trip included: Fishhook Spire (i.e., El Pima) and Big Baron Spire (i.e., Old Smoothy) in the Baron Creek drainage, Red Finger (i.e., North Raker) in the South Fork Payette drainage and The Grand Aiguille in the Redfish Lake drainage.

Fred, Pete, and Jack entered the Sawtooths by boating across Redfish Lake, then hiking 5 steep miles to Alpine Lake, where they left their “base camp” with a reserve cache of food and equipment. Then, with somewhat less-heavy packs, they hiked north over a pass to Baron Lakes and their first objectives. This was the era of heavy war-surplus gear and canned food for climbing trips, so their original packs likely each weighed in the 70 pound range. In 1948, Fred and Jack had been part of a group that failed in attempts on both Fishhook Spire and Big Baron Spire. On this trip, they had bolt equipment and more gear. They planned on achieving first ascents of each.

On the first day at Baron Lakes, they hiked up to Fishhook Spire’s East Face, donned tennis shoes and “wiggled up a series of steep dirt-filled chimneys to a tilted rock pile some hundred feet directly below the great overhang on the summit block.”

From there, they climbed a short jam crack and moved around to the North Side.

“Pete gave Fred a shoulder stand from the chockstone. Fred appeared to be stymied for a moment. It was the sort of pitch you almost wanted to try to climb free, but didn’t quite think you’d make. We decide to give the pitch the benefit of the doubt and resort to direct aid. Fred gingerly stepped on top of Pete’s outstretched hands and managed to drive a spoon piton at the limit of his reach. It was only partially in, but seemed solid enough for tension, so Fred went up on it until he could reach another crack. Two more very insecure pitons and he was able to hunch himself around onto a sloping ledge at the right from where the route became easy. Pete and I swung rapidly up on the rope to find Fred reclining on a large slab. A quick shoulder stand put us on the exposed summit.”

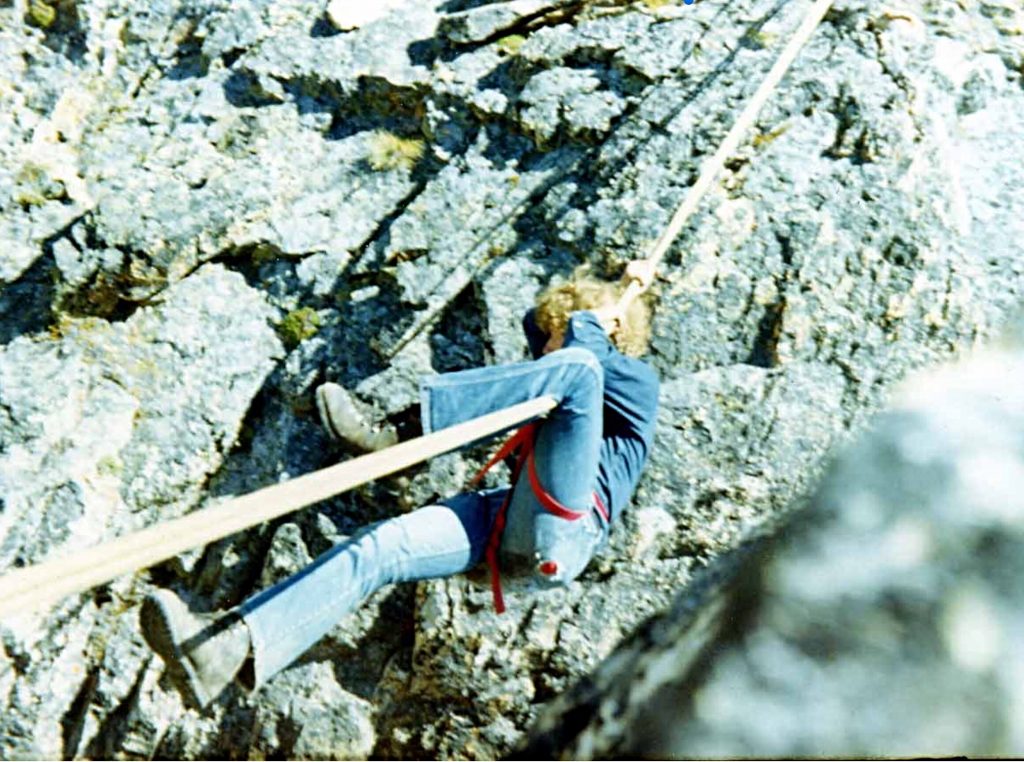

I climbed Fishhook Spire in 1971 with Harry Bowron by about the same route, although we knew nothing about the previous ascents. Toward the top, I gave Harry a shoulder stand, and later he made one aid move using a postage stamp sized piton called a RURP (realized ultimate reality piton). Our ascent was only the 3rd one since 1949.

Fred, Pete and Jack still had lots of time left in the day and decided to reconnoiter a route on Big Baron Spire. “We had no illusions about climbing it that day, but wanted to go as high as possible and find out what to expect.”

Every approach looked difficult, but they found some surprising lines of weakness that took them to the notch below the final ridge without roping up. Even above the notch, out on the West Face, they were able to scramble still higher before finally wanting ropes for safety. They then had some difficult climbing to the bottom of the 110 feet-high summit monolith.

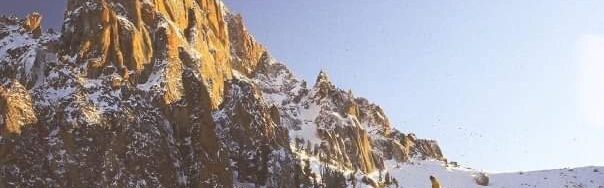

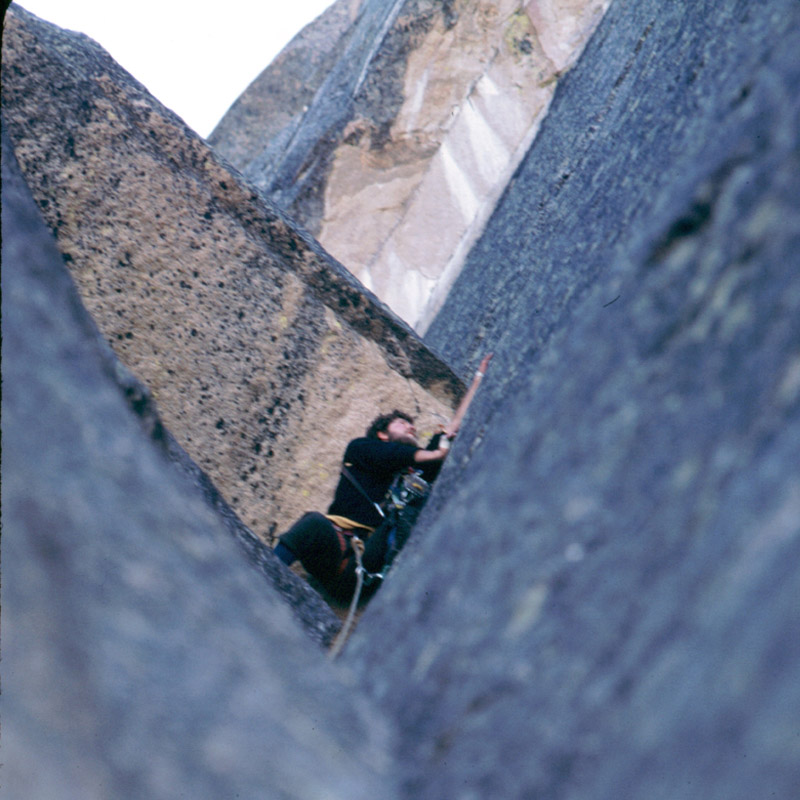

“We found ourselves perched on the North Shoulder of the peak with smooth walls plunging away beneath us on 3 sides and the summit soaring directly above, some 110 feet away. As we looked up at the great block, we could understand why the Iowa Mountaineers had dubbed it ‘Old Smoothy.’ It was a magnificent piece of rock, resembling nothing so much as a monster egg standing on its end atop the rest of the mountain. It overhung all the way around and, search as we might, we could not find a single crack or hold anywhere. Reluctantly, we hauled out our drills and bolts and prepared to do battle.”

“We decided to climb alongside the Northwest Corner, since that offered only 25 feet of overhang, followed by 35 feet of 75-degree slab, to a ridge where we hoped to find a hold or two. Pete mounted our shoulders to drill the first hole—-hurrying, because black clouds were rolling in from the southwest. Taking turns at drilling, we managed to place 7 bolts up the overhang and just get over onto the great slab before the rocks started buzzing with static electricity and an ominous rumbling informed us the storm was at hand.”

“We huddled under an overhang for more than an hour while lighting crackled about us and hail danced off the rocks. By the time the rock had dried enough to let us climb safely again, it was nearly dark. Leaving the hardware and one rope in place, we descended to camp, resolved to start early in the morning.”

Day Two of the climb on Big Baron Spire was long and exciting, and nearly resulted in the deaths of the climbers.

“As soon as it was light enough to see, we were pushing up the lower slopes again. The preliminary Class 3 and Class 4 rock climbing went rapidly and we found ourselves huddled on the shoulder once again while the sun was still near the horizon. Although it was bitterly cold, the weather was beautiful and we had high hopes of standing on the summit before sunset.”

“The drilling took much longer now, as the drills were getting duller and duller with each hole. We took turns at this unpleasant chore. Each man would place 2-3 bolts while the second man belayed and the third sharpened the extra drills. Late in the morning, I placed the 14th bolt just under the crest of the ridge, then dropped on tension to the shoulder. Fred replaced me on the rope and was hauled up to the highest bolt. By working up the sling and using his hands for balance, he succeeded in standing on the bolt and hauling himself astride the steeply-pitched ridge. Fifteen feet away was a tilted depression where, it seemed, a man might stand. This ‘bowl’ was the closest thing to a belay point on the whole summit block. Fred wormed over to it and put in a bolt for an anchor. He peered upward and saw that the arête above steepened again almost to the vertical. There appeared to be an occasional hold, but it still looked like a bolt job all the way.“

With the summit only 40 feet away, Fred had to rappel off the summit block when a new storm appeared.

“We held a council of war and determined to wait and try to finish the climb when the storm blew over. Hours passed by, while hail and freezing rain soaked us to the skin and lightning flashed in the murky sky. Finally we could see that it was getting dark and we decided to make a run for camp while we still could. We skidded around the slabby corner and raced down the ledge toward the wall above the finger traverse.”

“The rock was running with water, and every hold was packed with hail as we climbed down the wall. Pete started across the traverse just as the storm picked up in intensity. Lightning struck within 200 feet of us 3 times in quick succession. Pete reared back, blinded by the flashes, and it was several minutes before he could go on.”

“As the storm increased in fury, we all wondered whether we were to get down alive. The ’V’ crack was a terrible thing with water sluicing down its twisting length and lightning knifing all around. Fred and I took tension from the rope, while Pete half climbed, half fell as best he could. The remaining pitches were easier, but the lightning was still striking terrifyingly close.”

Back in camp, the beat-up climbers watched the storm clear and wondered if they were ever going to climb Big Baron Spire. The next morning, Pete had a wrenched shoulder and Dick a very sore ankle. Of course, they went back up on the mountain. This time both Fred and Pete climbed up to the top of the bolt ladder and Pete started to the top.

After a shoulder stand and four more bolts: “Pete was clinging to a tiny projection only 15 feet from the top. Things were looking up.”

Pete climbed free to the summit and clasped his hands in the victory sign. A total of 20 bolts had been placed. The climbers were so wary of another approaching lightning storm, that Jack didn’t follow Pete and Fred to the summit. However, they had no more storms that day and were able to go back over to their base camp at Alpine Lake.

In the 1970s, I climbed Big Baron Spire 3 times by two different routes that Harry Bowron and I pioneered. When we first arrived at the bottom of the bolt ladder in 1971: what we saw was a long line of rusted and bent ¼” diameter bolts without hangers. The bolts looked horrible, some appeared to be missing, and we did not have the gear to climb the dilapidated bolt ladder. On a 1977 ascent, we brought bolt hangers and bolting gear, but were thwarted by a thunderstorm that forced us back off the mountain.

Since I was last at the summit block in 1977, some Good Samaritan had put hangers on the old ¼” bolts and replace those that were missing when we were there. In 2009, I shared emails with Radek Chalupa, who climbed the bolt ladder in late Summer 2009. From his account, it appears that at least some of the missing or unusable bolts have been replaced, but the classic Fred Beckey drill bit remains.

During a rest day back at their Alpine Lake base camp, Fred and Pete made the decision to make the long off-trail hike west into the South Fork Payette drainage to the remote “Red Finger” (i.e., North Raker). Jack would stay at Alpine Lake, and rest his injured leg.

Besides presenting an enticing profile, when viewed from afar, the attraction of North Raker was that climbing legend Robert Underhill had attempted it during the first of his two Summers of exploration and climbing in the Sawtooth Range in 1934-35. Underhill may have been the best male rock climber in North America at the time and his wife Miriam was certainly the best female climber, but they were not able to climb North Raker. No recorded attempts on its remote summit had been made since 1934. [Miriam Underhill, “Give Me The Hills,” 1956]

Fred and Pete worked south from Alpine Lake and traversed off-trail into the Upper Redfish Lakes Basin. They ignored nearby attractive summits and slogged up a 10,074-foot pile of rubble called Reward Peak. The summit of Reward, which sits on the divide between the Redfish Lake Creek drainage and the South Fork Payette drainage, gave them a good view of the approach to North Raker. From Reward Peak, they dropped 3,400 vertical feet to the South Fork Payette, forded it in hip-deep water and explored up Fall Creek on the South Side of The Rakers (there is also a South Raker that the Underhills did climb in 1934).

I hiked with my wife Dorita and 2 fit young friends up the South Fork Payette in late August 2009 and, with some searching, discovered a large log spanning the river just above Elk Lake. Our group found the trail-less terrain leading up Fall Creek to be difficult, wet, loose and brushy. Fred and Pete likely thought it almost pleasant, when compared to their usual cold-jungle bushwhacking in the North Cascade Range.

After camping a couple of miles up Fall Creek, the next morning Fred and Pete followed grassy open hillsides to a lake basin on the East Side of The Rakers. From there, North Raker looked rather difficult to them.

They hiked up to the saddle to the right/north of North Raker and then discovered that its West Face was more welcoming to climbers. Without roping-up, they were able to scramble to the cairn that marked the high point of Robert Underhill’s 1934 attempt. From this point, it was less than 100 feet to the top of the summit tower, but the route looked hopeless from all sides.

“A rope-length traverse was made over considerable exposure to the notch on the North Corner of the peak. Fred anchored to a piton and the climb began.” “Pete traversed right about 15 feet and reached an overhanging crack that appeared to lead somewhere.The crack was composed of a crumbling granitic rubble which took several direct-aid pitons in one place at one time to be even reasonably safe.“

“Fifteen feet of this, over a space of an hour, convinced Pete that he wanted a rest. Accordingly, he lowered himself back to the notch and Fred took over. He hammered in a giant angle piton behind a loose chockstone, hoping it would act as a wedge and tighten everything up.

Above this, the crack being absolutely smooth and rather useless for a way, Fred drilled a hole and drove in a solid-sounding bolt. This had a decidedly reassuring effect on his jangled nerves, since the drop was still 500 feet and the quality of the pitons below him was such that any kind of fall would have made them all pop out like buttons from a shirt.”

Pete took over again and managed to place two pitons and a bolt (their drill was so dull, it was nearly useless) before switching with Fred. Fred placed another piton and another bolt and could see the end of the overhanging section just above. After another trade, Pete was able to climb a 3” wide jam-crack to a ledge. Then with the help of a shoulder stand, Fred jam-cracked another 12 feet to the summit.

They enjoyed the tiny summit for a few minutes, Pete claimed a lone-eagle feather and then started down. By nightfall, they were back across the South Fork Payette and had climbed to within only 1,100 vertical feet of the pass into Redfish Lake Creek.

The next day, they returned to camp at Alpine Lake after making the 3rd ascent of Packrat Peak 10,240 Feet. They loosely followed the route Robert Underhill used to make the 1st ascent of Packrat with his wife Miriam and local packer Dave Williams in 1934. Fred and Pete had a pleasant Class 3-4 scramble on the complex but forgiving East Face.

When they arrived at Alpine Lake in the late afternoon, they found a note from Jack that he had departed for the social life at Redfish Lake. Fred and Pete packed up the remaining gear and trudged back down the trail to the upper end of Redfish Lake and camped, since they planned to climb the nearby Grand Aiguille the next day. Jack picks the story back up at this point.

“As a gesture of friendship, Fred decided to hike around the lake (5 miles with quite a bit of elevation gain and loss) to the lodge to tell me of their plans in case I could go with them. He arrived just in time to join me at a beach party I was having with a couple of heartening samples of the unattached females who infested the place. I reluctantly informed him that I would not be able to climb in the morning, but that I would be glad to row him back to save him the 5-mile walk. Thus 4:30AM found us sleepily stroking a rowboat up the lake. Unearthly yodels as we rounded the point informed us that Pete was up and had breakfast ready. An hour later, they started off while I hitched a ride back on the ever-present tourist launch.”

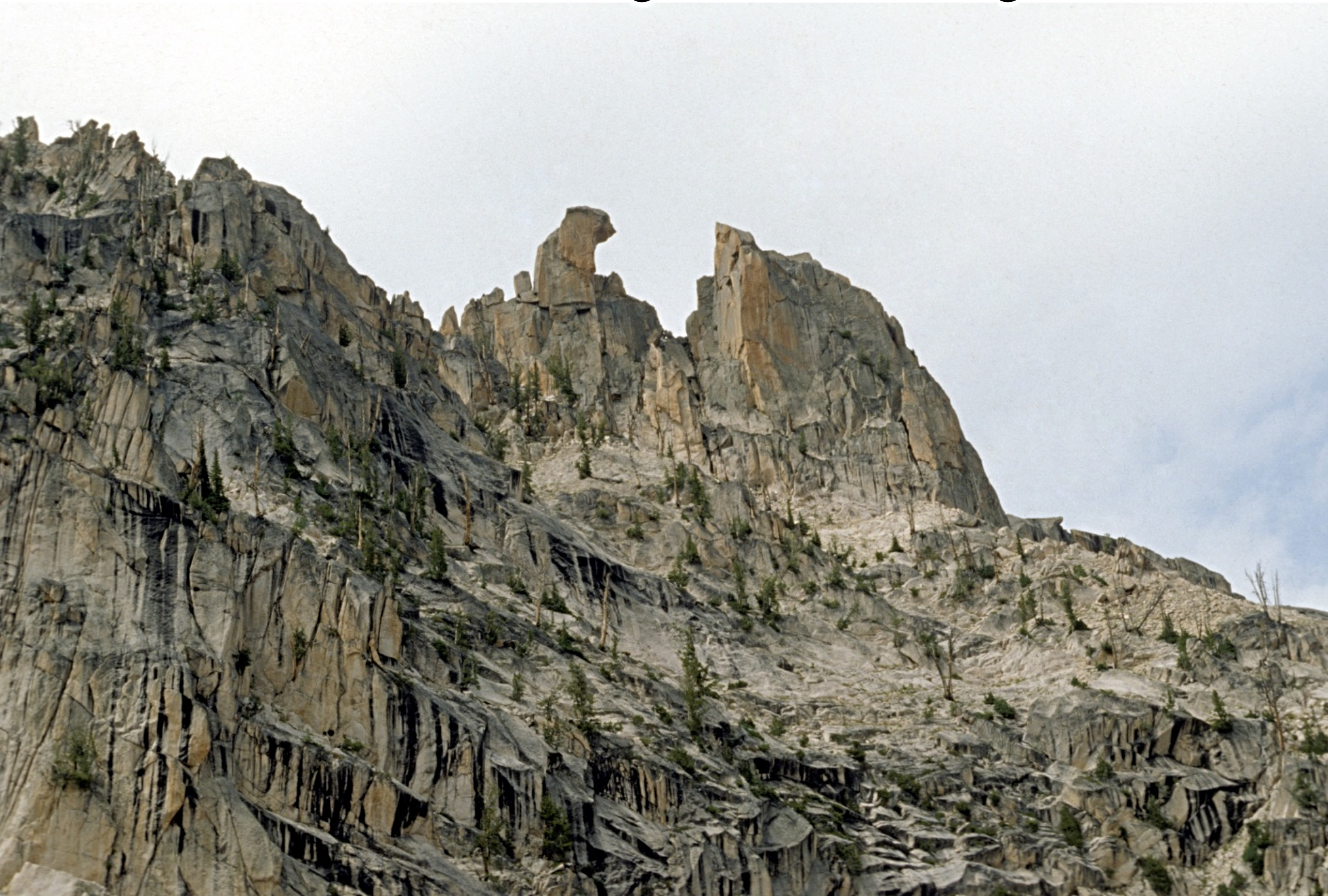

The Grand Aiguille is a prominent formation above the South End of Redfish Lake. Its first ascent in 1946 is rated Class 5.4 and apparently the rock tower was of interest to Fred and Pete. It is described in Tom Lopez’s fine book “Idaho: A Climbing Guide,” but that area of the Sawtooth Range has a reputation for “ball-bearing” granite and I had never trudged up to the small cirque it is in until early September 2011.

It is several miles and about 3,000 vertical feet from Redfish Lake to the top of the Grand Aiguille. Fred and Pete knocked the 2nd ascent off and were back at Redfish Lake Lodge shortly after noon.

“They reported a spectacular Class 4 and Class 5 climb on good rock, the crux of which was a vertical crack jammed with overhanging chockstones.”

After hiking up to the route with Dorita, equipped with a 9mm rope and minimal technical climbing gear, I suffered a reality check when looking for possible easy routes. I can only commend Fred and Pete for their fortitude and speed on the Grand Aiguille. It looked like more of a challenge than I wanted at the time.