[Editor’s Note: Art Troutner is a pioneering Idaho mountaineer who was involved in many firsts in the 1970s including the first Winter ascent of Mount Borah. In this article, he writes about a difficult first ascent of the Lick Creek Range’s most compelling North Face.]

On July 4th, 1973, Bill Whitman (19 years old) and I (18 years old) made the first ascent of the North Face of Snowslide Peak. We took my brother Jim Cockey’s rack of Lost Arrow pitons and around ten Bongs and my diminutive rack of nuts and chocks along with one 90-foot length of Goldline nylon rope and an assortment of white slings, also on loan from my brother.

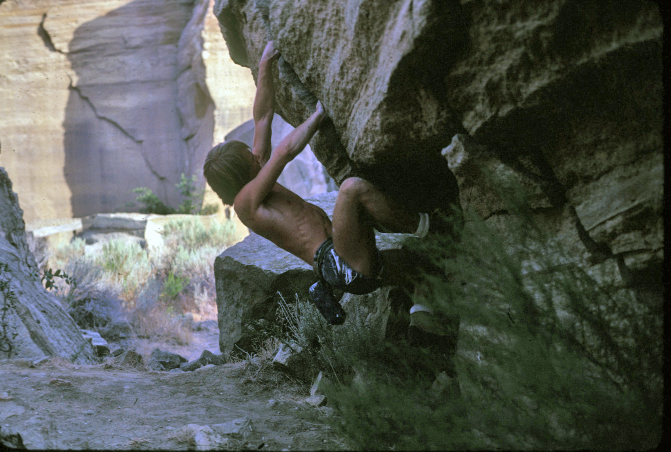

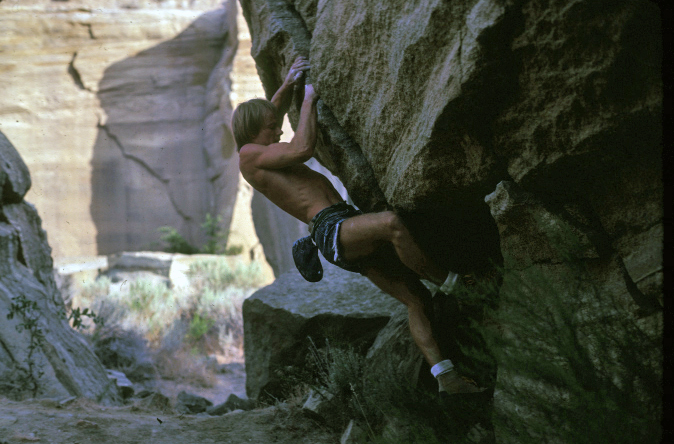

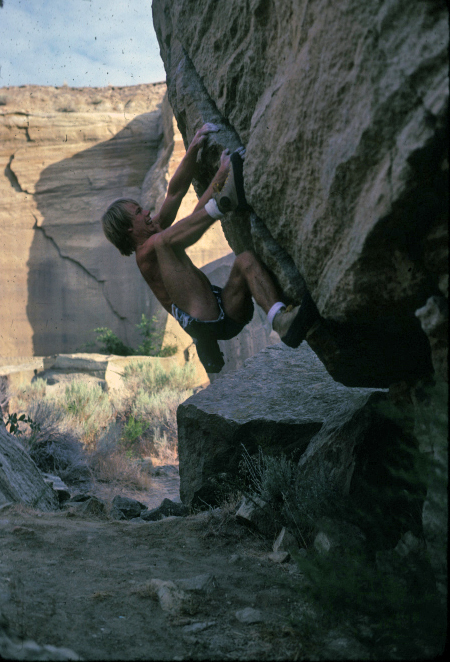

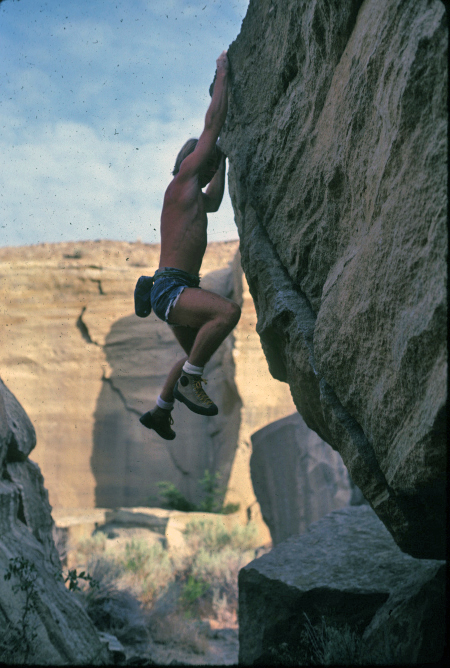

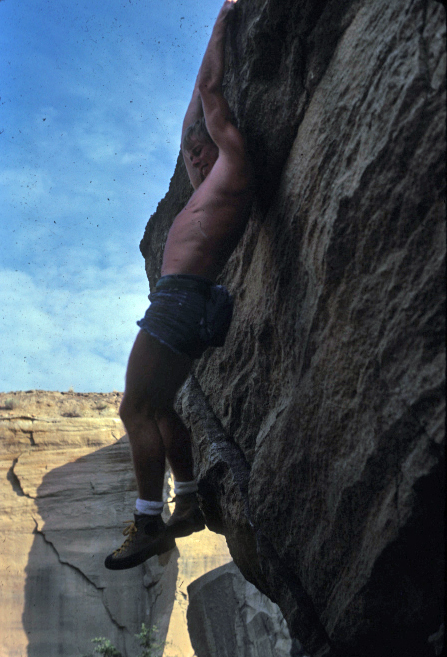

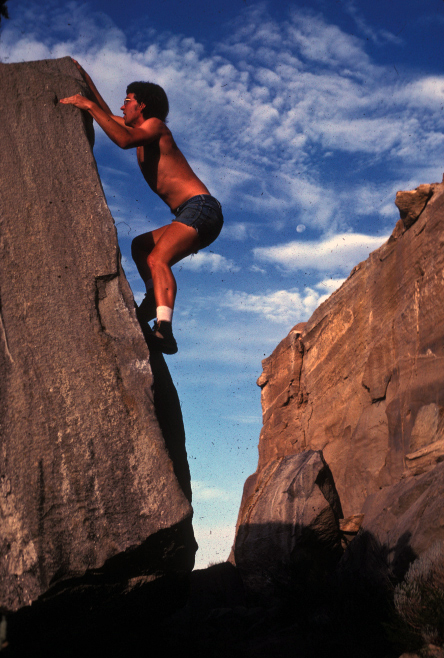

When my brother had gone off to college, he loaned his climbing equipment to Bill who was forever borrowing it to climb Slick Rock. We suspected Bill’s infatuation with Slick Rock was more often than not used as a ploy to introduce some young lovely to the wonders of rock climbing. We hoped the best for Bill in his endeavors but never found out the results as he was not a braggart. All the same, due to his frequent infatuations, he racked up quite a lot of rock time on Slick Rock. So Jim figured Bill was a worthy recipient of the gear. Lord knows I had considerably less of the gumption that Bill showed for getting out on the rock.

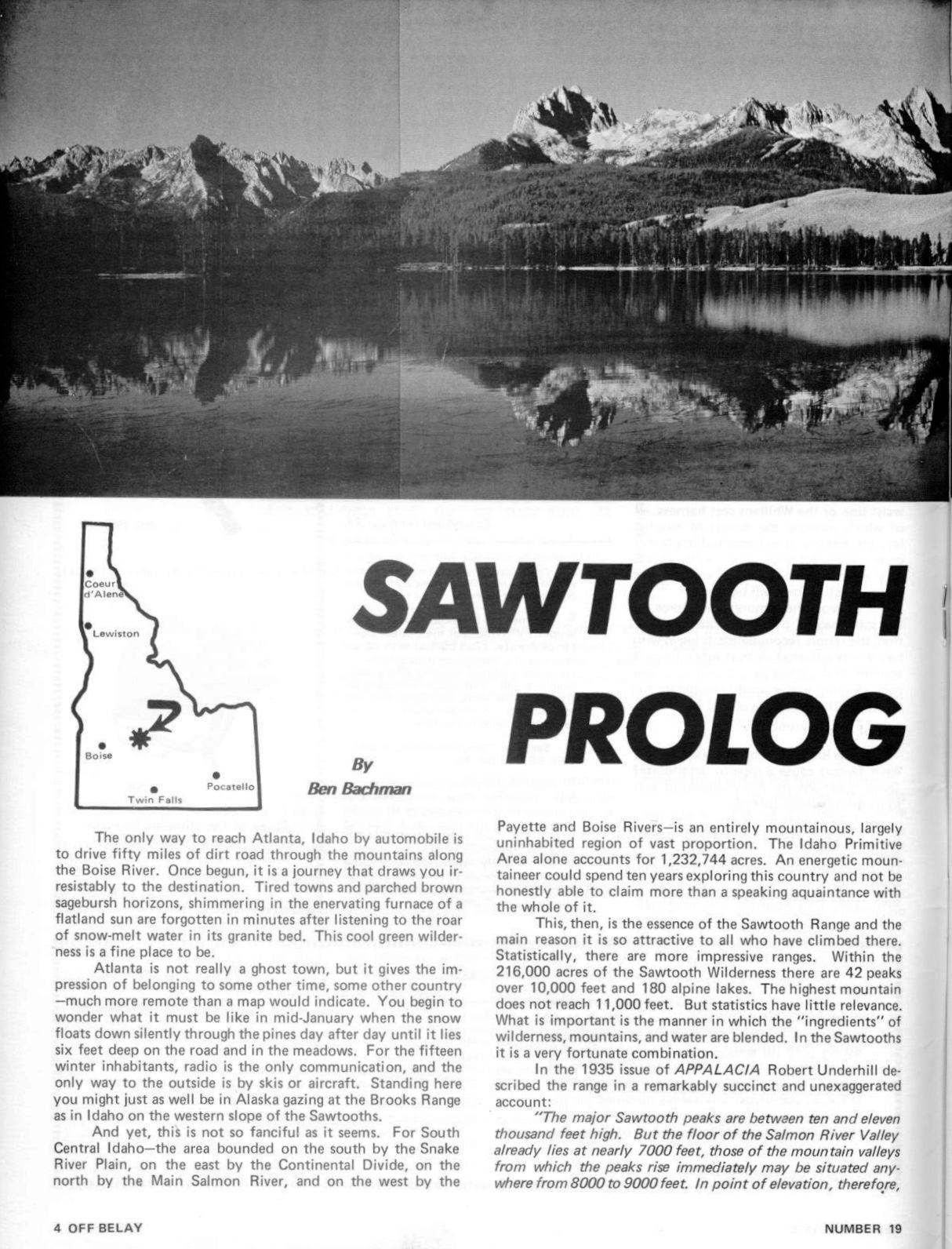

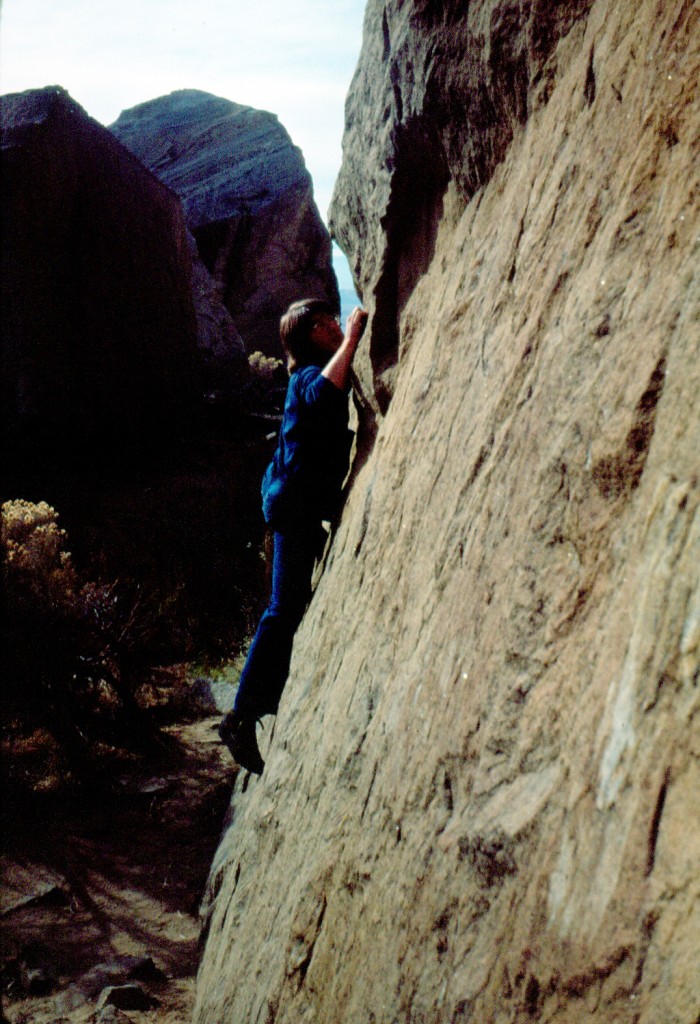

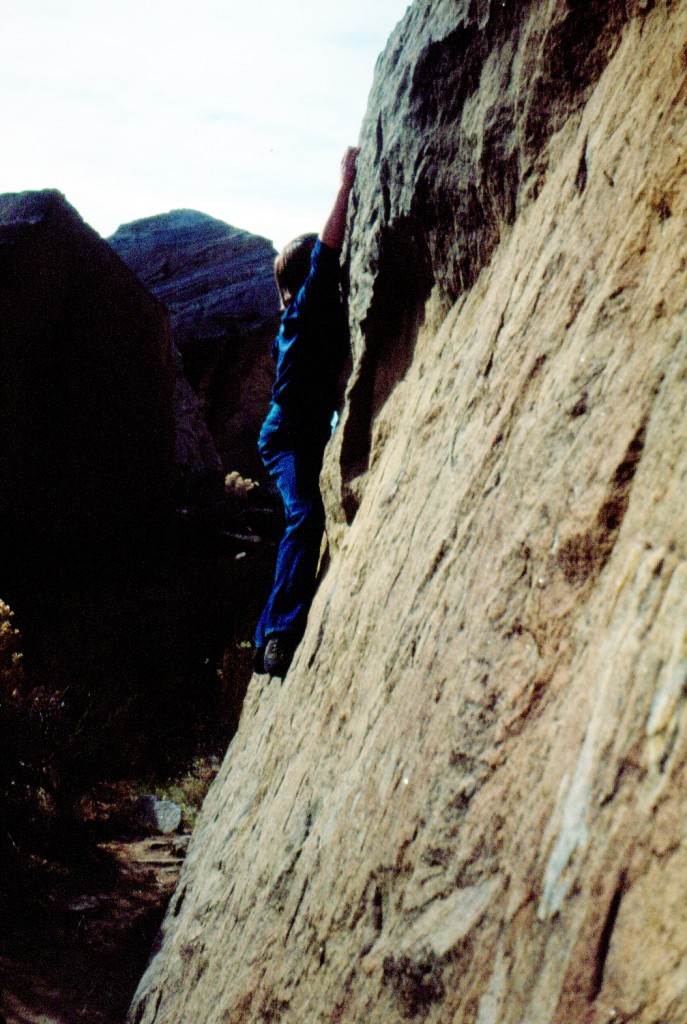

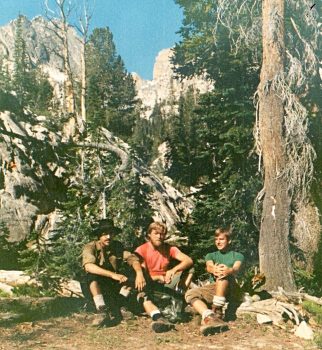

All the same, I was intrigued by Snowslide’s imposing North Face and thought it was something I’d like to work up to. The fact that none of us knew anyone who had climbed it was an incentive that was hard to ignore. When I was 16, I was working on a house my dad and uncle were working on in Stanley, I used my free time to started gaining some climbing experience in the Sawtooths.

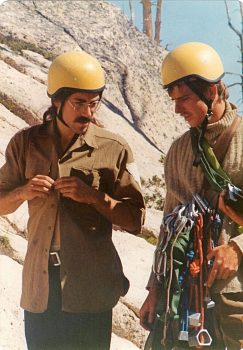

Now comes some jostling of my memory as to the sequence of events, but I believe the house construction was the same Summer that Jerry Osborn and I attempted the Finger of Fate, climbed the Stur Chimney Route on Heyburn, and climbed the back side of Finger of Fate.

Jerry lead the first pitch which, though not very exposed, is the most technical pitch. From there we traded leads. We used 2 ropes and 3 climbers. Jerry brought along a photographer acquaintance who we roped up between us.

The attempt on the Finger of Fate involved a nasty slog in overripe Spring snow. I feel that we, in our utter ignorance, were smiled upon by the gods as I now know that the snow should have slid and ended my little story right there. At some point in the day, we realized our predicament and shifted over to the south a bit to some thin snow and navigable rock where we “felt” safer in our retreat to our sodden camp. We avoided a possible disaster and learned a lot from the experience.

So working up to the Snowslide climb included a couple trips up the Open Book on the Finger and a trip up Warbonnet with Pierre Saviers. One of the Open Book excursions was in September 1972. This was a 2-team effort that met at the top for a group photo which included one of our party (Tom McLeod) posed while intensely studying his Physics book. Tom’s photo won the honor of gracing the Wall behind our physics teacher’s desk.

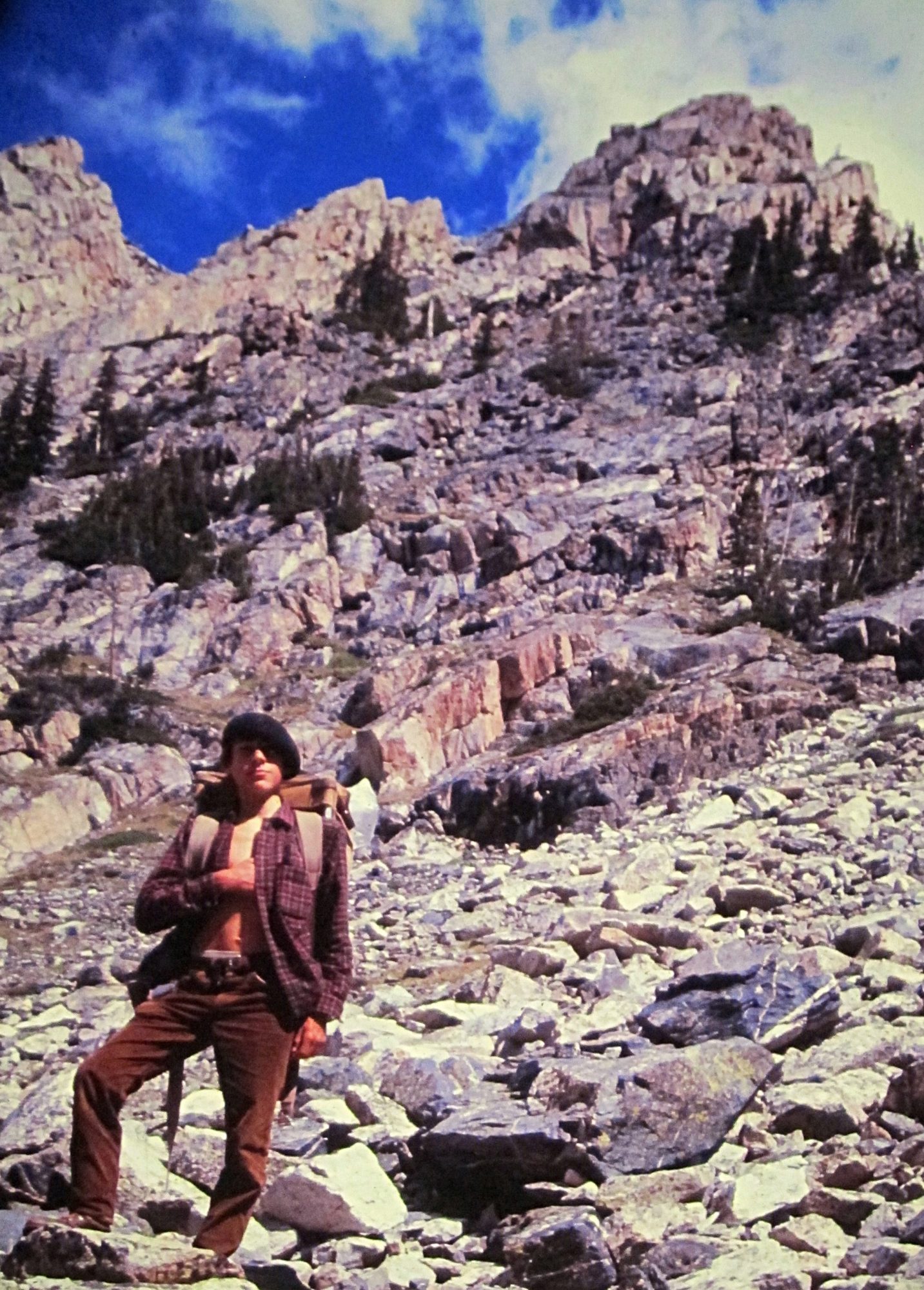

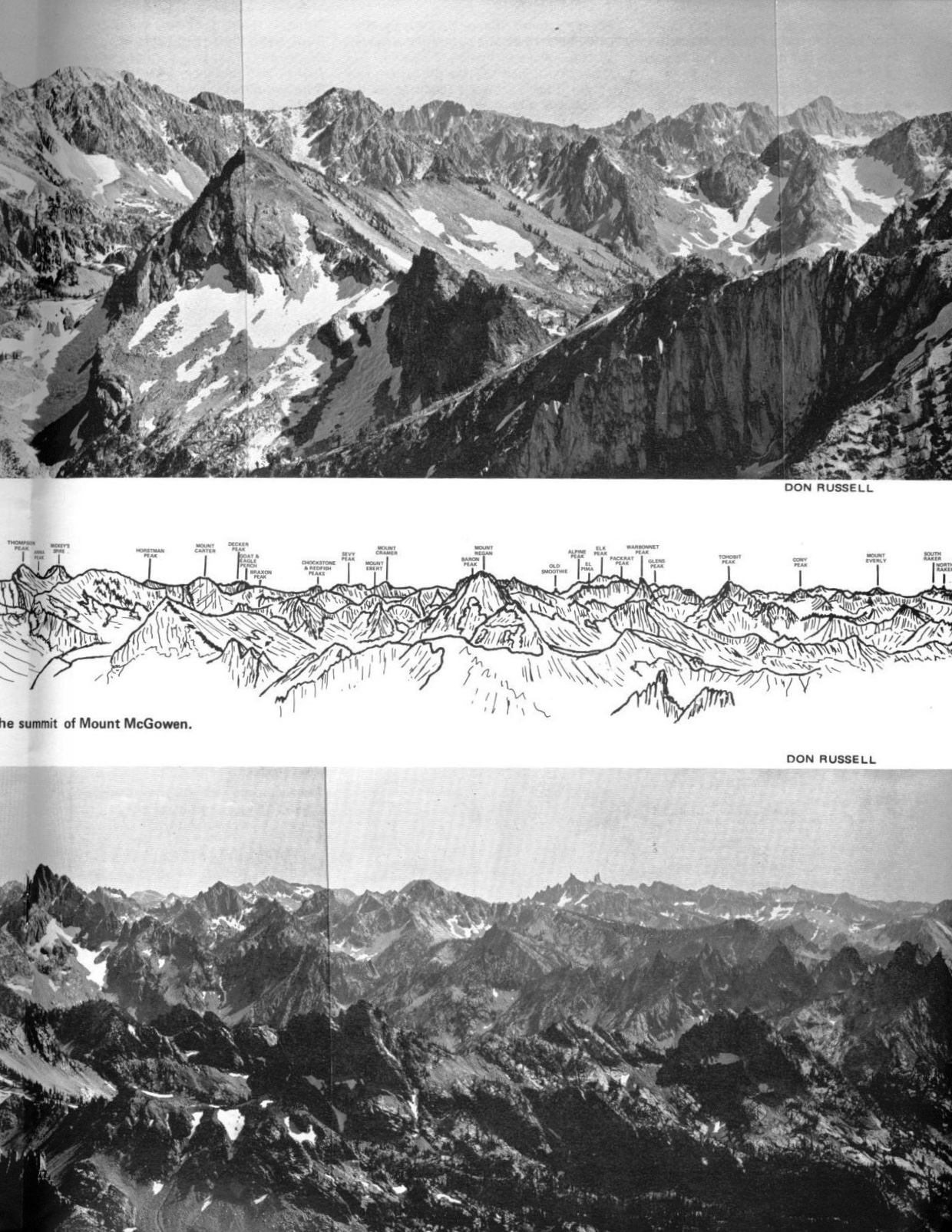

Anyway, by the time July 1973 rolled around, I must have felt enough seasons had taken place to attempt the dark and vertical North Face of Snowslide Peak. The day of the climb we were up at dawn, drove my Mom’s Citroen at speed to the trailhead and were hiking by 7:30AM. About 45 minutes later, we arrived at the lake and made our way around to the base. Here we encountered the permanent snow field (not anymore) that wedged up against the start of the climb. This was a favorite boot glissading spot on previous trips to the lake.

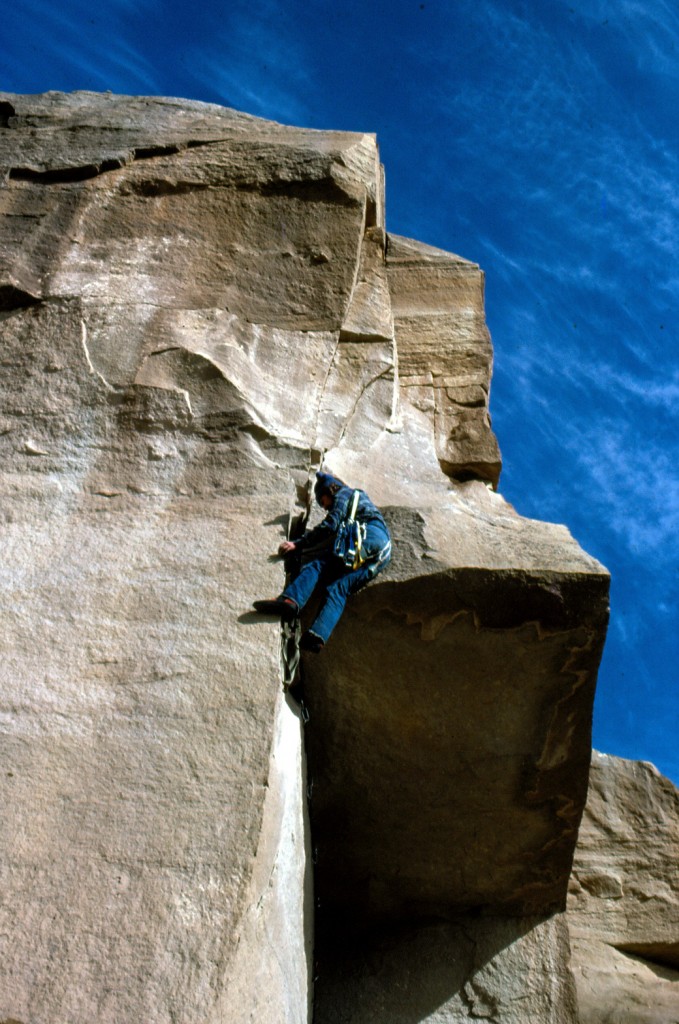

The “route” from here was pretty simple. The face is concave but trending to a V shape on its right side. As long as we stayed in the V we knew it would lead us to the high point of the face. As the face is very fractured for its entire length we just ascended what looked easiest and didn’t stray too far left or right. There were plenty of holds but many of them were loose. We had to be very careful to not drop any rocks down the face as we belayed. All in all, it was not pleasant rock to deal with. We never felt very confident in the protection or the belay anchors we set.

The overall face is very steep with several small, reach-over type, overhanging ledges. Fortunately, there were places where we could gather our wits a bit and rest. I remember them as pockets where 2 could sit. The rock was consistently loose until a couple of rope lengths from the top where things improved.

As it is a north facing, very steep face, the temperatures for the 4th of July were quite cool. While climbing, we watched folks at the lake bathing. It seemed quite incongruous but also somehow reassuring or even comforting to see some normality as we felt quite cut off from that.

We realized early on in the climb that retreating off this thing did not present a pretty picture. The realization was that the best way down was up. So, we got lucky. The face was consistent: loose holds and steep, but doable. Just had to pay attention to the holds and not drop anything on the belay man.

We got to the top around 3:30PM to the sounds of bleating sheep who were grazing unconcernedly right up to the 800+ foot drop. We were elated to have arrived! The sheep not so much. Our reward? Beer and Brass Lamp pizza by 6:00PM.