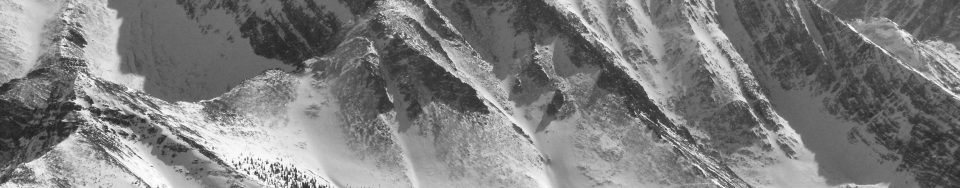

When Robert and Miriam Underhill first gazed from the top of Galena Summit in Idaho’s Sawtooth Wilderness, before them stretched a wild mountain panorama never before seen by mountaineers. It was 1934 and in those days the road past the future site of Sun Valley to the summit was little more than a rutted sheep wagon track. Approaching the remote and rugged central Idaho mountains was a long, slow trip, but the Underhills were keenly aware of the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity awaiting them in the Sawtooths.

The educated and well-to-do Underhill was hardly a newcomer to mountaineering. He had an impressive resume of ascents in the Alps to his credit, and is generally regarded as one of America’s most influential early climbers. As editor of the outdoor journal “Appalachia”, Underhill spread his enthusiasm and knowledge of technical climbing through the pages of his journal and on his frequent climbing trips to the Rockies and the Canadian mountains.

Underhill became “a driving force” in Wyoming’s Teton Range, establishing the bold North Ridge route on the Grand Teton in 1931, a climb that was considered the most difficult in the country at the time. Having made his mark on the well-trodden Tetons, the insightful Underhill ventured north to the unexplored Sawtooths, lured perhaps by rumors of virgin peaks and soaring rock towers.

After a long journey, Robert and his wife Miriam finally made their way to the glacially- sculpted Sawtooth Valley, where they recruited local homesteader and mountain-lover Dave Williams to serve as outfitter and guide. In a few short weeks, the three adventurers pioneered the first ascents of over twenty of the Sawtooths highest peaks, including Mt. Thompson [10,759 feet] and the formidable Mt. Heyburn [10,229 feet].

Williams turned out to be not only a fine companion but quite an able cragsman who reportedly preferred to climb the more difficult pitches barefoot! Although they usually took the easiest route up the peaks, their pioneering efforts and sheer quantity of first ascents stands out as a fine accomplishment of rare opportunity.

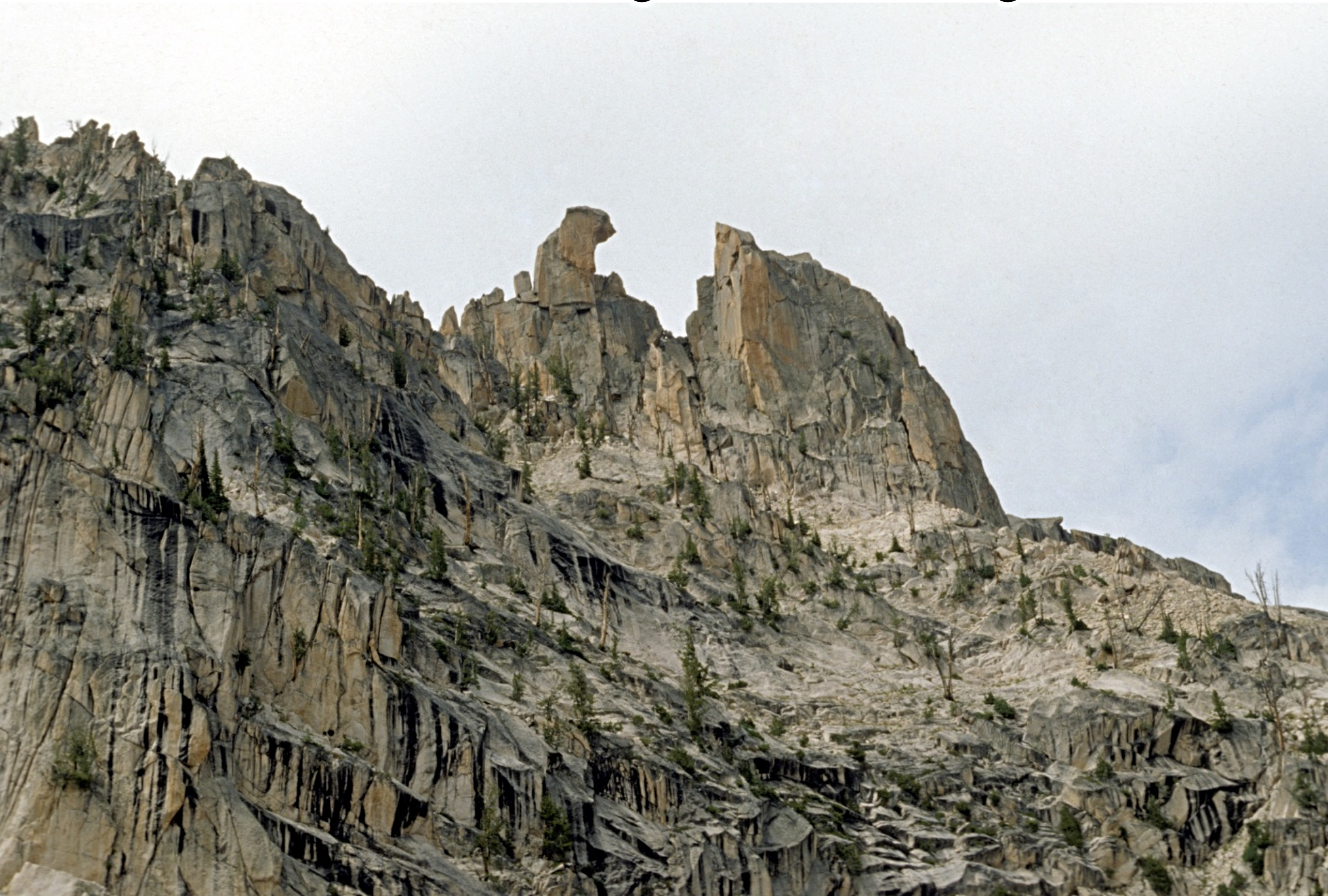

Returning to work as editor of “Appalacia”, Underhill wrote of the Sawtooths: “I think there is quite a lot to engage the interest of the rock climber…“ and “two of the summits we could not master, nor do I believe that they are surmountable except by throwing a rope since they are sheer monoliths.” Underhill also reported “Rock towers of the genuine Chamonix aiguille type, each several hundred feet high which would provide magnificent ascents if they could be climbed at all.”

The situation in the 1930’s was a far cry from today, yet it seems the motives of the early climbers haven’t changed much over the years. When L.G. Darling made a trip to the Sawtooths in 1940 he commented, “we all agreed on two very important points: we all wanted to get to the top of Mt. Heyburn and we all liked to eat.”

The range was mostly quiet for several years following the Underhills visit, and World War II put a stop to what little climbing activity there was. Two notable Teton climbers (Dick and Jack Durrance) did manage a quick visit in 1940, to attempt the higher of the two “aiguilles“ described by Underhill. They reportedly came close to making the summit but were turned back by oncoming darkness.

It wasn’t until 1946 that a group of Iowa Mountaineers, guided by Teton hardman Paul Petzolt, made any significant ascents. On the club outing, they succeeded in a number of climbs including a landmark ascent of one of the Sawtooths most-ominous towers, the spectacular Warbonnet Peak. After some difficulty in finding a feasible route from the west side, the group of six (with Petzolt and Bill Echo in the lead) made the top via an exposed summit ridge [Class 5.6].

The ascent of Warbonnet was an ambitious project for the day. A later climber described the final pitch like this: “The sheer walls on either side of the rooftop overhang menacingly into nothingness below. Holds are a bare minimum and piton cracks zero.” The first ascent party also wrote that Warbonnet “should be classified with the few really difficult summits in this country.“

Warbonnet is located in the rugged heart of the Sawtooths, surrounded by numerous peaks and smaller rock towers beyond the abilities of the Iowa Mountaineers. The group did name several peaks though, including “Fishhook Tower“, “La Fiama”, and a monolithic peak they dubbed “Old Smoothie”. Of the latter they wrote: “One of the most striking rock pinnacles in the country; a smooth spire of granite topped by an obelisk that has an overhang on all four sides”.

In those days, pitons were just beginning to gain wide acceptance, and aid climbing was even considered something of a cheat. Modern aid techniques were unknown, so when Petzolt did a new route on Mount Heyburn using a controversial two-rope tension system, it was heralded as “the latest development in technical climbing.”

Following their 1947 Sawtooth outing, the Iowa Mountaineers devoted several articles on the range in their annual club journal. There were stunning photos of the spires in the Warbonnet area and maps of their approaches. The word on the Sawtooths was out and spreading among the country’s top climbers. It was now only a matter of time before the arrival of Fred Beckey.

In 1949, Beckey descended on the Sawtooths. In typical fashion, Beckey eliminated dozens of aesthetic and difficult routes from his first ascent list. Ruthlessly exploring nearly every corner of the range, Beckey brought with him a level of energy and ability far above the mere mortals who came before.

Unlike many of his conservative predecessors, he used pitons, bolts, and direct aid liberally. On his first ascent of “Old Smoothie“, Beckey surmounted the flawless summit block with a 22-bolt ladder! This marathon drilling session is unequaled in the range and possibly unrepeated due to removed bolts.

A lot has been said about the poor quality of Sawtooth granite. At its best, the stone is as good as any in the world, while much of the rock, especially on the easier routes, is decomposing and gravelly. The “ball bearing“ granite can certainly be discouraging and has been described as having a texture “more like that of a stale donut.” But the abundance of bad rock did little to deter Beckey, who on his ascent of Underhill’s “Grand Aiguille“ reportedly drove his aid pitons directly into the rock!

In the Sawtooths as elsewhere, Beckey preferred not to climb any route that was not a first ascent. The following story, told by one of Fred’s Sawtooth partners, Louis Stur, illustrates: “We were climbing a route on a little tower called Silicon Peak, near Warbonnet. We assumed that the route was a first ascent but as I was leading the last pitch, probably not more than 30 feet from the summit, when I discovered a piton. I had to call down to Fred and Jim Ball and say, Gentlemen, I’m sorry to say but I’ve found a piton! Beckey got absolutely furious! He said “You should have known this peak had been climbed! You guys are locals! So Fred wouldn’t go on to the top, he just announced “We’re going down.”

As it turned out, they had actually made the first ascent of a new route, a route that joined Colorado climber Harvey Carter’s first ascent route just short of the summit. Carter had come to the Sawtooths in 1956 with a returning group of Iowa Mountaineers. The outing that year included such noteworthy climbers as Herb and Jan Conn, who pioneered routes in New Hampshire and in the Needles of South Dakota. Also on the team were Joe and Paul Stettner, the “working class climbers” who made important explorations on Colorado’s East Face of Longs Peak.

Carter and a partner hiked into the pristine Baron Lakes drainage, where they made the ascent on Silicon Peak and several other smaller towers. The rest of the group kept busy doing repeat ascents in the Heyburn and Thompson areas, plus a first ascent of the unusually-shaped Chockstone Peak. Still, the outing was essentially a pleasure trip and did little to advance local standards.

Around the same time, skier-climber types, who worked at the nearby ski resort of Sun Valley, began to establish more difficult routes on the peaks. Louis Stur, a charming native Hungarian and now manager of the Sun Valley lodge, was one of the most active. Unaware of any prior mountaineering activity, Stur and friends re-explored the range and made numerous ascents. In 1958, Stur established a route on Mt. Heyburn that has since become the most popular route on the mountain due to its relatively high-quality rock. Louis also teamed up with Beckey on several occasions until the time when Beckey, according to Stur, “went on to bigger and better things.”

It was the summer of 1963 when Beckey did just that. Together with Steve Marts and Herb Swedlund, Beckey tackled the most formidable wall in the Sawtooths: a unique Yosemite-like face known as the “Elephant’s Perch.” This 1,200-foot wall was climbed with much aid and with ropes fixed over nearly the entire route. It was the first Grade V in the range, and represented a giant leap in scope and technical difficulty over any other Sawtooth peak. So despite the fixed ropes and several bolts, the route stands as a fine achievement, not far from the standards being set in comfortable Yosemite, yet in a remote wilderness setting. A typical Beckey route, it follows a beautiful natural line up the highest part of the face. The grade, also typically Beckey, is Class 5.8/A2, of course.

A couple years later, in 1965, the Iowa Mountaineers returned for a third time. Unlike on their previous visits, the mountaineers placed their base camp at the far end of Redfish Lake, where access to the peaks was much better. Hans Gmoser, an Austrian guide living in Canada, was hired and led a number of new routes out of Redfish Creek. Among these was the Eagle Perch, a classic rock tower that Gmoser likened to the Piz Badile in the Alps.

Teaming up with Bill Echo and others, Gmoser made another first: an airy aid climb up the intimidating pillar of Flatrock Needle. Still, nothing was done that equaled Beckey’s route on the Elephant’s Perch. Interestingly, the group even reported in their journal that they had made the first ascent of the Perch that year, via a scramble up the northwest slopes!

Beckey returned to the Sawtooths several more times over the years, always adding new routes. Louis Stur, with various partners, circled Warbonnet with routes. But with the majority of peaks and spires having been climbed, the scene was stagnating. The time had come for new blood in the Sawtooths and a new concept of what climbing was all about.

It was the late 1960’s, and California’s Yosemite Valley was the breeding ground for a host of new ideas, energy, and equipment. Somehow, a few stray Yosemite climbers found their way to Idaho where their influence took root. No longer interested in peak-bagging, the new arrivals focused their attention on the most Yosemite-like feature in the range: the Elephant’s Perch.

Gordon Webster had moved to Sun Valley and was one of the first of the Yosemite clan to recognize the possibilities in the Sawtooths. In California, Webster had established a number of fine free climbs in the Valley and elsewhere, including the first ascent of the classic “Travelers Buttress” [Class 5.9] at Lovers Leap.

In 1968, Yosemite guidebook author Steve Roper teamed up with Webster for a trip to the Elephant’s Perch. They chose a bold line on the East Face, a clean five hundred foot high dihedral they named “the Sunrise Book” [A3+]. Over the next two summers, Gordon and friends established two more Grade V routes on the main wall and a few shorter lines. One of Websters partners was Rob Kiessel, who went on to partake in the first winter ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome, and later became head coach of the U.S. National Nordic Ski Team. Nut protection was just catching on when Jeff Lowe and Dick Dorworth made a “clean” ascent of the Beckey Route, which had required 110 piton on the first ascent.

It should be noted that although the rock type and actual climbing on the Perch was similar to that in Yosemite, the remote wilderness setting made the climbing far more committing and serious. No trails lead to the wall and climbers were forced to traverse the 5-mile Redfish Lake by boat, follow the creek for a few more miles, and finally haul their loads up 1,500 feet of rock slabs and talus slopes. Any effort on the Perch entailed a multi-day effort with no hope of rescue in case of a mishap.

Nonetheless, more and more climbers took up residence in the Sun Valley area and the list of routes on the Perch steadily grew. Other smaller crags were also explored, purely for their free-climbing potential.

It was not until 1976, however, that the first Class 5.10 came to the Sawtooths. That summer, two young climbers (Jeff Hall and Jim Catlin) visited the Perch, establishing two major routes on the main wall. “Myopia” and “Hook and Ladder” both required sophisticated aid techniques as well as hard free climbing. Tragically, Jeff Hall was killed in Yosemite a few years later in a climbing accident.

The following year (1977) marked the arrival of a young thrillseeker from Georgia who was to become the Perch’s most prolific route developer. Reid Dowdle had spent several summers in Yosemite, the Tetons and elsewhere, working the usual odd jobs to support his climbing and skiing habits. When Dowdle discovered the Sawtooths and the great backcountry skiing to be had in the winter months, he was hooked. He decided to make Sun Valley/Ketchum his home.

Since then, Dowdle has repeated all of the Perch’s established routes and added at least seven others. In his characteristic independent manner, Reid would haul loads of food and climbing gear up to a bivouac at the base of the rock, waiting for the outside chance that someone would show up needing a partner. If no one showed, Dowdle would simply rope solo his chosen Grade V. Other local climbers made their mark on the Sawtooths, although often on shorter routes of moderate difficulty. Olympic downhill skier Pete Patterson was active and, with four time “Survival of the Fittest“ contest winner Kevin Swigert, climbed several off-the-beaten-path routes.

Jeff Lowe returned in 1981, enlisting Swigert for a new route on the North Face of Warbonnet Peak. Their “Black Crystal Route” has several Class 5.10 pitches followed by a free version of Beckey’s bolt ladder on the summit block at Class 5.11+. Although the climb was considerably harder than anything done before, it remained an isolated incident. The major new route activity was still firmly dominated by Dowdle and friends. But just when Dowdle’s dominance seemed assured, a pair of talented and aggressive hotshots from the east arrived to stir things up.

Honed and psyched, Jeff Gruenburg and Gene Smith hit the Perch intent on, in their words, “rape and pillage.” Armed with cheap Chablis, strong fingers, and strict Shawangunks ethics, the “gunkies” went directly to Beckey’s original route, set on making it a free climb. They succeeded in their goal except for a ten-foot tension traverse on the first pitch, creating a superbly sustained free climb with six Class 5.10 pitches in a row followed by more Class 5.9 and Class 5.10.

When the team came into the local mountain shop announcing that they had made the first free ascent of the Beckey Route, they were surprised to learn that Dowdle had made the same ascent the week before! A small controversy was stirred up when the New Yorkers expressed doubt whether the locals had done the route in clean style. Questioning if rests were taken on protection, they stated “Where we come from, when we say free, we mean free-free!”

Despite a few hard feelings, who gets credit for the first free ascent of the Beckey Route is of little consequence. What is important is that the New Yorkers had stirred up the local scene and encouraged development of a higher standard of free climbing. Before they left, the gunkies free climbed the Catlin-Hall route “Myopia” at a thinly protected Class 5.11, and added a three pitch Class 5.11+ pitch they dubbed “the Wendy.”

The next year (1983), Gruenburg returned to the Perch, this time with another Shawngunk regular, Jack Milesky. For the easterners, the prospect of clean, multi-pitch first free ascents was almost too good to be true. Describing his winter training program Gruenburg pantomimed doing pullups, saying “ten more…for the Perch!”.

They began by cleaning up the remaining aid on Webster and Roper’s Sunrise Book, freeing the original A3+ dihedral at Class 5.11+, followed by the crux Class 5.12 pitch. The pair also pulled off an as-yet unrepeated new route consisting of thin discontinuous cracks with difficult sections of poorly-protected face. With no bolt kit, hammer, or pitons, they climbed in bold style a route that would likely have seen bolts had it been done by locals.

In the past couple of years still more routes have been added to the Perch and surrounding peaks. February 1984 saw the first winter ascent* of the Perch, a siege of the Beckey Route. Most of the better quality aid routes in the range have been free climbed and the Perch has been free soloed.

Still, there are always new routes to do, although the pioneering days are over. And even though climbers have been to every corner of the range, local climbers like to think of the Sawtooths, and especially the Perch, as a big secret. In a way it is, or at least it feels that way. But this is probably due more to Idaho’s remote location and a difficult approach than any other factor.

For the locals, this is a good thing. We like the peace, solitude, and mosquitos of our backyard mountains. Over the years the climbers come and go, luckily without leaving many signs of their passing. The mountains themselves remain much the same as when Robert and Miriam Underhill first explored the peaks over fifty years ago.

*[Editor’s Note: The winter ascent of the Perch was done by Paul Potters, Steve Morris (from Boulder) and Dave Bingham.]