Tag: 1980s

-

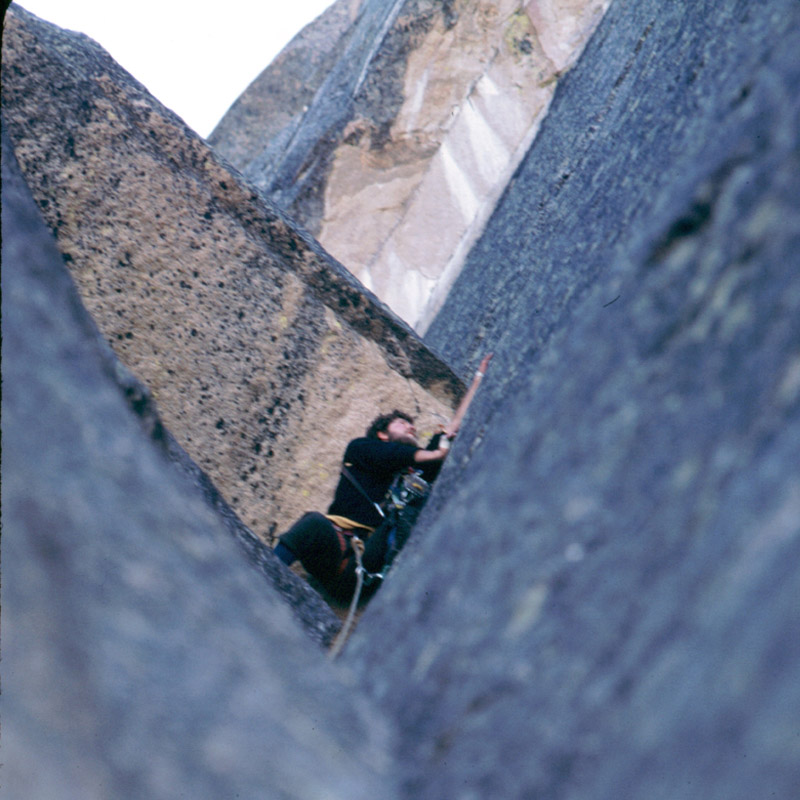

The City of Rocks and Dave Bingham

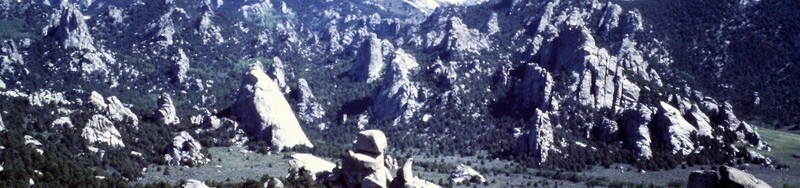

The City of Rock, a land of spectacular granite formations at the southern end of the Albion Range, was a stop in the 1840s along the historic California Trail. This trail forked off the Oregon Trail. Memoirs written by California Trail travelers momentarily brought some national notoriety to what was then known as the “Silent City of Rock.” After the railroads spanned the continent pioneers no longer traveled crosscountry by Conestoga. The City was forgotten by most and became the home of ranchers and a few settlers. The City’s status would remain silent for many years.

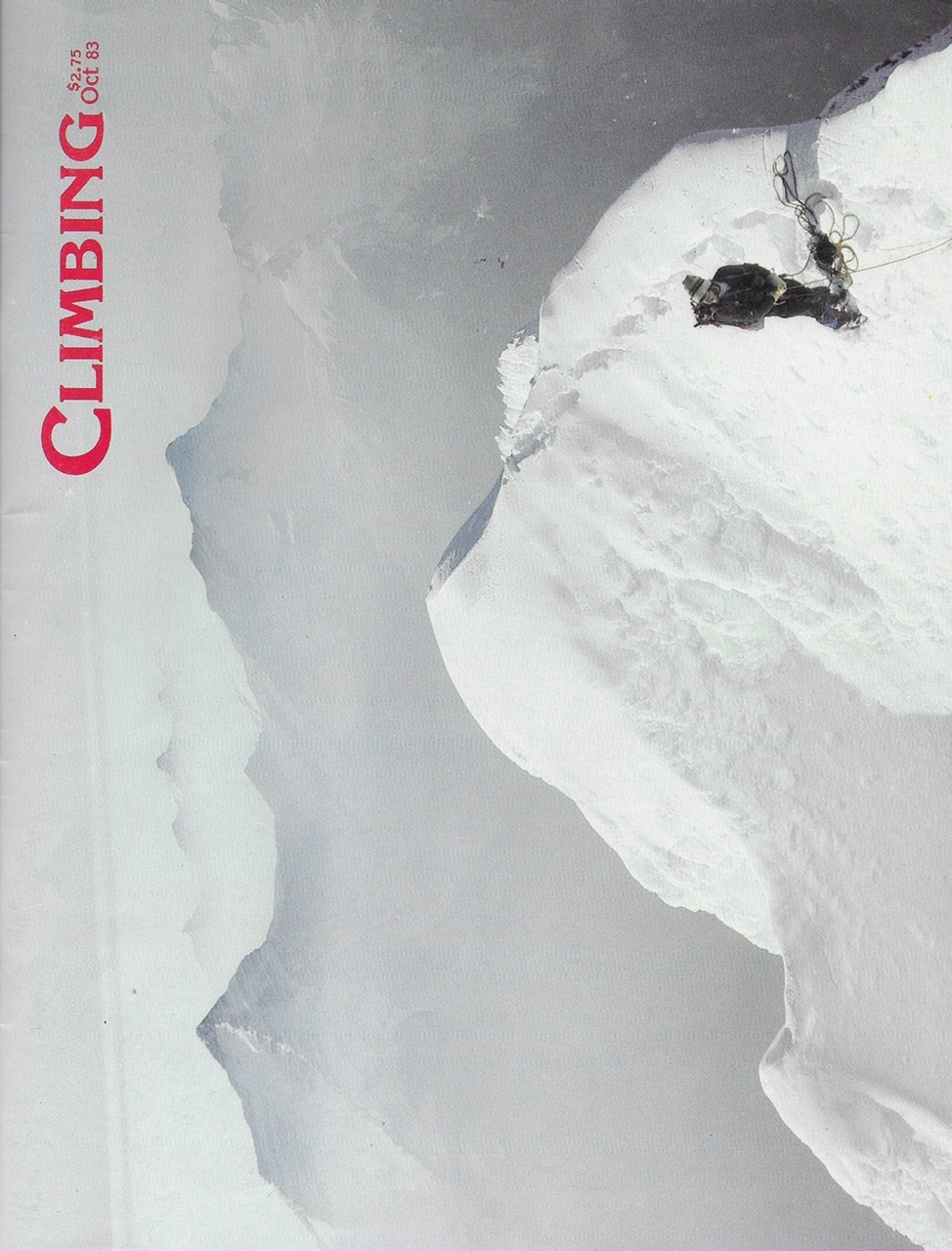

Dave Bingham first visited the City of Rocks in 1978. At that time the City was the quintessential “off-the-radar” climbing destination. Over the next few years the City’s popularity took off and politics and conflicting uses exploded into controversy. (See Politics, Climbing History and Need, Climbing, No. 80, October 1983) In 1985 Dave published the first guidebook documenting the few known climbing routes. Historically, Dave is credited with publishing Idaho’s first climbing guidebook. From a climbing perspective the guidebook was one of the catalyst for ensuring that rock climbing and rock climbers would have a seat at the table as land managers discussed the City’s future.

As the City evolved from a nearly forgotten in time stop along the California Trail into a busy climbing and recreational destination manages as a National Preserve so has Dave’s guidebook. Now in its 8th edition, the book has evolved over the past 35 years it is a comprehensive guide covering over a thousand climbing routes as well as the area’s history and climbing lore, camping and nearby amenities and bouldering, hiking and mountain biking opportunities.

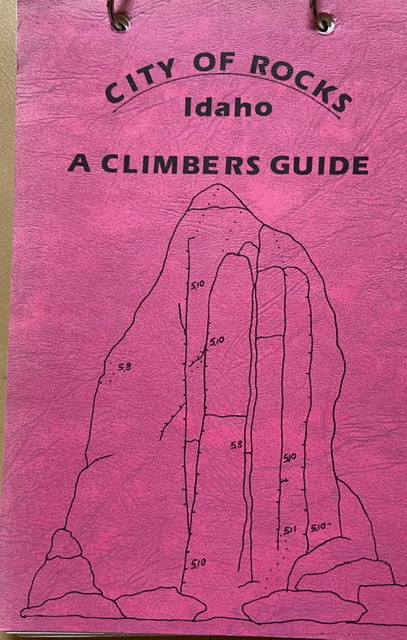

The original 1985 guidebook.

The 2016 version of guidebook. -

FIFTY YEARS OF SAWTOOTH CLIMBING 1934-1984 By Dave Bingham

When Robert and Miriam Underhill first gazed from the top of Galena Summit in Idaho’s Sawtooth Wilderness, before them stretched a wild mountain panorama never before seen by mountaineers. It was 1934 and in those days the road past the future site of Sun Valley to the summit was little more than a rutted sheep wagon track. Approaching the remote and rugged central Idaho mountains was a long, slow trip, but the Underhills were keenly aware of the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity awaiting them in the Sawtooths.

The educated and well-to-do Underhill was hardly a newcomer to mountaineering. He had an impressive resume of ascents in the Alps to his credit, and is generally regarded as one of America’s most influential early climbers. As editor of the outdoor journal “Appalachia”, Underhill spread his enthusiasm and knowledge of technical climbing through the pages of his journal and on his frequent climbing trips to the Rockies and the Canadian mountains.

Underhill became “a driving force” in Wyoming’s Teton Range, establishing the bold North Ridge route on the Grand Teton in 1931, a climb that was considered the most difficult in the country at the time. Having made his mark on the well-trodden Tetons, the insightful Underhill ventured north to the unexplored Sawtooths, lured perhaps by rumors of virgin peaks and soaring rock towers.

After a long journey, Robert and his wife Miriam finally made their way to the glacially- sculpted Sawtooth Valley, where they recruited local homesteader and mountain-lover Dave Williams to serve as outfitter and guide. In a few short weeks, the three adventurers pioneered the first ascents of over twenty of the Sawtooths highest peaks, including Mt. Thompson [10,759 feet] and the formidable Mt. Heyburn [10,229 feet].

Williams turned out to be not only a fine companion but quite an able cragsman who reportedly preferred to climb the more difficult pitches barefoot! Although they usually took the easiest route up the peaks, their pioneering efforts and sheer quantity of first ascents stands out as a fine accomplishment of rare opportunity.

Returning to work as editor of “Appalacia”, Underhill wrote of the Sawtooths: “I think there is quite a lot to engage the interest of the rock climber…“ and “two of the summits we could not master, nor do I believe that they are surmountable except by throwing a rope since they are sheer monoliths.” Underhill also reported “Rock towers of the genuine Chamonix aiguille type, each several hundred feet high which would provide magnificent ascents if they could be climbed at all.”

The situation in the 1930’s was a far cry from today, yet it seems the motives of the early climbers haven’t changed much over the years. When L.G. Darling made a trip to the Sawtooths in 1940 he commented, “we all agreed on two very important points: we all wanted to get to the top of Mt. Heyburn and we all liked to eat.”

The range was mostly quiet for several years following the Underhills visit, and World War II put a stop to what little climbing activity there was. Two notable Teton climbers (Dick and Jack Durrance) did manage a quick visit in 1940, to attempt the higher of the two “aiguilles“ described by Underhill. They reportedly came close to making the summit but were turned back by oncoming darkness.

It wasn’t until 1946 that a group of Iowa Mountaineers, guided by Teton hardman Paul Petzolt, made any significant ascents. On the club outing, they succeeded in a number of climbs including a landmark ascent of one of the Sawtooths most-ominous towers, the spectacular Warbonnet Peak. After some difficulty in finding a feasible route from the west side, the group of six (with Petzolt and Bill Echo in the lead) made the top via an exposed summit ridge [Class 5.6].

The ascent of Warbonnet was an ambitious project for the day. A later climber described the final pitch like this: “The sheer walls on either side of the rooftop overhang menacingly into nothingness below. Holds are a bare minimum and piton cracks zero.” The first ascent party also wrote that Warbonnet “should be classified with the few really difficult summits in this country.“

Warbonnet is located in the rugged heart of the Sawtooths, surrounded by numerous peaks and smaller rock towers beyond the abilities of the Iowa Mountaineers. The group did name several peaks though, including “Fishhook Tower“, “La Fiama”, and a monolithic peak they dubbed “Old Smoothie”. Of the latter they wrote: “One of the most striking rock pinnacles in the country; a smooth spire of granite topped by an obelisk that has an overhang on all four sides”.

In those days, pitons were just beginning to gain wide acceptance, and aid climbing was even considered something of a cheat. Modern aid techniques were unknown, so when Petzolt did a new route on Mount Heyburn using a controversial two-rope tension system, it was heralded as “the latest development in technical climbing.”

Following their 1947 Sawtooth outing, the Iowa Mountaineers devoted several articles on the range in their annual club journal. There were stunning photos of the spires in the Warbonnet area and maps of their approaches. The word on the Sawtooths was out and spreading among the country’s top climbers. It was now only a matter of time before the arrival of Fred Beckey.

In 1949, Beckey descended on the Sawtooths. In typical fashion, Beckey eliminated dozens of aesthetic and difficult routes from his first ascent list. Ruthlessly exploring nearly every corner of the range, Beckey brought with him a level of energy and ability far above the mere mortals who came before.

Unlike many of his conservative predecessors, he used pitons, bolts, and direct aid liberally. On his first ascent of “Old Smoothie“, Beckey surmounted the flawless summit block with a 22-bolt ladder! This marathon drilling session is unequaled in the range and possibly unrepeated due to removed bolts.

A lot has been said about the poor quality of Sawtooth granite. At its best, the stone is as good as any in the world, while much of the rock, especially on the easier routes, is decomposing and gravelly. The “ball bearing“ granite can certainly be discouraging and has been described as having a texture “more like that of a stale donut.” But the abundance of bad rock did little to deter Beckey, who on his ascent of Underhill’s “Grand Aiguille“ reportedly drove his aid pitons directly into the rock!

In the Sawtooths as elsewhere, Beckey preferred not to climb any route that was not a first ascent. The following story, told by one of Fred’s Sawtooth partners, Louis Stur, illustrates: “We were climbing a route on a little tower called Silicon Peak, near Warbonnet. We assumed that the route was a first ascent but as I was leading the last pitch, probably not more than 30 feet from the summit, when I discovered a piton. I had to call down to Fred and Jim Ball and say, Gentlemen, I’m sorry to say but I’ve found a piton! Beckey got absolutely furious! He said “You should have known this peak had been climbed! You guys are locals! So Fred wouldn’t go on to the top, he just announced “We’re going down.”

As it turned out, they had actually made the first ascent of a new route, a route that joined Colorado climber Harvey Carter’s first ascent route just short of the summit. Carter had come to the Sawtooths in 1956 with a returning group of Iowa Mountaineers. The outing that year included such noteworthy climbers as Herb and Jan Conn, who pioneered routes in New Hampshire and in the Needles of South Dakota. Also on the team were Joe and Paul Stettner, the “working class climbers” who made important explorations on Colorado’s East Face of Longs Peak.

Carter and a partner hiked into the pristine Baron Lakes drainage, where they made the ascent on Silicon Peak and several other smaller towers. The rest of the group kept busy doing repeat ascents in the Heyburn and Thompson areas, plus a first ascent of the unusually-shaped Chockstone Peak. Still, the outing was essentially a pleasure trip and did little to advance local standards.

Around the same time, skier-climber types, who worked at the nearby ski resort of Sun Valley, began to establish more difficult routes on the peaks. Louis Stur, a charming native Hungarian and now manager of the Sun Valley lodge, was one of the most active. Unaware of any prior mountaineering activity, Stur and friends re-explored the range and made numerous ascents. In 1958, Stur established a route on Mt. Heyburn that has since become the most popular route on the mountain due to its relatively high-quality rock. Louis also teamed up with Beckey on several occasions until the time when Beckey, according to Stur, “went on to bigger and better things.”

It was the summer of 1963 when Beckey did just that. Together with Steve Marts and Herb Swedlund, Beckey tackled the most formidable wall in the Sawtooths: a unique Yosemite-like face known as the “Elephant’s Perch.” This 1,200-foot wall was climbed with much aid and with ropes fixed over nearly the entire route. It was the first Grade V in the range, and represented a giant leap in scope and technical difficulty over any other Sawtooth peak. So despite the fixed ropes and several bolts, the route stands as a fine achievement, not far from the standards being set in comfortable Yosemite, yet in a remote wilderness setting. A typical Beckey route, it follows a beautiful natural line up the highest part of the face. The grade, also typically Beckey, is Class 5.8/A2, of course.

A couple years later, in 1965, the Iowa Mountaineers returned for a third time. Unlike on their previous visits, the mountaineers placed their base camp at the far end of Redfish Lake, where access to the peaks was much better. Hans Gmoser, an Austrian guide living in Canada, was hired and led a number of new routes out of Redfish Creek. Among these was the Eagle Perch, a classic rock tower that Gmoser likened to the Piz Badile in the Alps.

Teaming up with Bill Echo and others, Gmoser made another first: an airy aid climb up the intimidating pillar of Flatrock Needle. Still, nothing was done that equaled Beckey’s route on the Elephant’s Perch. Interestingly, the group even reported in their journal that they had made the first ascent of the Perch that year, via a scramble up the northwest slopes!

Beckey returned to the Sawtooths several more times over the years, always adding new routes. Louis Stur, with various partners, circled Warbonnet with routes. But with the majority of peaks and spires having been climbed, the scene was stagnating. The time had come for new blood in the Sawtooths and a new concept of what climbing was all about.

It was the late 1960’s, and California’s Yosemite Valley was the breeding ground for a host of new ideas, energy, and equipment. Somehow, a few stray Yosemite climbers found their way to Idaho where their influence took root. No longer interested in peak-bagging, the new arrivals focused their attention on the most Yosemite-like feature in the range: the Elephant’s Perch.

Gordon Webster had moved to Sun Valley and was one of the first of the Yosemite clan to recognize the possibilities in the Sawtooths. In California, Webster had established a number of fine free climbs in the Valley and elsewhere, including the first ascent of the classic “Travelers Buttress” [Class 5.9] at Lovers Leap.

In 1968, Yosemite guidebook author Steve Roper teamed up with Webster for a trip to the Elephant’s Perch. They chose a bold line on the East Face, a clean five hundred foot high dihedral they named “the Sunrise Book” [A3+]. Over the next two summers, Gordon and friends established two more Grade V routes on the main wall and a few shorter lines. One of Websters partners was Rob Kiessel, who went on to partake in the first winter ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome, and later became head coach of the U.S. National Nordic Ski Team. Nut protection was just catching on when Jeff Lowe and Dick Dorworth made a “clean” ascent of the Beckey Route, which had required 110 piton on the first ascent.

It should be noted that although the rock type and actual climbing on the Perch was similar to that in Yosemite, the remote wilderness setting made the climbing far more committing and serious. No trails lead to the wall and climbers were forced to traverse the 5-mile Redfish Lake by boat, follow the creek for a few more miles, and finally haul their loads up 1,500 feet of rock slabs and talus slopes. Any effort on the Perch entailed a multi-day effort with no hope of rescue in case of a mishap.

Nonetheless, more and more climbers took up residence in the Sun Valley area and the list of routes on the Perch steadily grew. Other smaller crags were also explored, purely for their free-climbing potential.

It was not until 1976, however, that the first Class 5.10 came to the Sawtooths. That summer, two young climbers (Jeff Hall and Jim Catlin) visited the Perch, establishing two major routes on the main wall. “Myopia” and “Hook and Ladder” both required sophisticated aid techniques as well as hard free climbing. Tragically, Jeff Hall was killed in Yosemite a few years later in a climbing accident.

The following year (1977) marked the arrival of a young thrillseeker from Georgia who was to become the Perch’s most prolific route developer. Reid Dowdle had spent several summers in Yosemite, the Tetons and elsewhere, working the usual odd jobs to support his climbing and skiing habits. When Dowdle discovered the Sawtooths and the great backcountry skiing to be had in the winter months, he was hooked. He decided to make Sun Valley/Ketchum his home.

Since then, Dowdle has repeated all of the Perch’s established routes and added at least seven others. In his characteristic independent manner, Reid would haul loads of food and climbing gear up to a bivouac at the base of the rock, waiting for the outside chance that someone would show up needing a partner. If no one showed, Dowdle would simply rope solo his chosen Grade V. Other local climbers made their mark on the Sawtooths, although often on shorter routes of moderate difficulty. Olympic downhill skier Pete Patterson was active and, with four time “Survival of the Fittest“ contest winner Kevin Swigert, climbed several off-the-beaten-path routes.

Jeff Lowe returned in 1981, enlisting Swigert for a new route on the North Face of Warbonnet Peak. Their “Black Crystal Route” has several Class 5.10 pitches followed by a free version of Beckey’s bolt ladder on the summit block at Class 5.11+. Although the climb was considerably harder than anything done before, it remained an isolated incident. The major new route activity was still firmly dominated by Dowdle and friends. But just when Dowdle’s dominance seemed assured, a pair of talented and aggressive hotshots from the east arrived to stir things up.

Honed and psyched, Jeff Gruenburg and Gene Smith hit the Perch intent on, in their words, “rape and pillage.” Armed with cheap Chablis, strong fingers, and strict Shawangunks ethics, the “gunkies” went directly to Beckey’s original route, set on making it a free climb. They succeeded in their goal except for a ten-foot tension traverse on the first pitch, creating a superbly sustained free climb with six Class 5.10 pitches in a row followed by more Class 5.9 and Class 5.10.

When the team came into the local mountain shop announcing that they had made the first free ascent of the Beckey Route, they were surprised to learn that Dowdle had made the same ascent the week before! A small controversy was stirred up when the New Yorkers expressed doubt whether the locals had done the route in clean style. Questioning if rests were taken on protection, they stated “Where we come from, when we say free, we mean free-free!”

Despite a few hard feelings, who gets credit for the first free ascent of the Beckey Route is of little consequence. What is important is that the New Yorkers had stirred up the local scene and encouraged development of a higher standard of free climbing. Before they left, the gunkies free climbed the Catlin-Hall route “Myopia” at a thinly protected Class 5.11, and added a three pitch Class 5.11+ pitch they dubbed “the Wendy.”

The next year (1983), Gruenburg returned to the Perch, this time with another Shawngunk regular, Jack Milesky. For the easterners, the prospect of clean, multi-pitch first free ascents was almost too good to be true. Describing his winter training program Gruenburg pantomimed doing pullups, saying “ten more…for the Perch!”.

They began by cleaning up the remaining aid on Webster and Roper’s Sunrise Book, freeing the original A3+ dihedral at Class 5.11+, followed by the crux Class 5.12 pitch. The pair also pulled off an as-yet unrepeated new route consisting of thin discontinuous cracks with difficult sections of poorly-protected face. With no bolt kit, hammer, or pitons, they climbed in bold style a route that would likely have seen bolts had it been done by locals.

In the past couple of years still more routes have been added to the Perch and surrounding peaks. February 1984 saw the first winter ascent* of the Perch, a siege of the Beckey Route. Most of the better quality aid routes in the range have been free climbed and the Perch has been free soloed.

Still, there are always new routes to do, although the pioneering days are over. And even though climbers have been to every corner of the range, local climbers like to think of the Sawtooths, and especially the Perch, as a big secret. In a way it is, or at least it feels that way. But this is probably due more to Idaho’s remote location and a difficult approach than any other factor.

For the locals, this is a good thing. We like the peace, solitude, and mosquitos of our backyard mountains. Over the years the climbers come and go, luckily without leaving many signs of their passing. The mountains themselves remain much the same as when Robert and Miriam Underhill first explored the peaks over fifty years ago.

*[Editor’s Note: The winter ascent of the Perch was done by Paul Potters, Steve Morris (from Boulder) and Dave Bingham.]

-

The Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club By Ray Brooks

I guess we were the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club (DFC&FC) before anyone, including us, knew. The little guy in the back of my mind liked the way the words fit together. Until the name popped into my head we were simply a group of like-minded climbers who lacked an identifying name. However, on a fateful morning in the mountains of Idaho, adversity transformed us from a nameless, ragged band of climbers into an organization that would accomplish endless deeds of climbing derring-do.

The fateful day was a hot one in late July 1970. We were hiking into Mount Regan above Sawtooth Lake. Our packs were heavy, each with 60-70 pounds of climbing and camping gear. In addition to the heat, it was a humid and windless morning. We were sweating hard and were being chased mercilessly by a full-strength squadron of horseflies.

Flies dive-bombed us incessantly, trying to break through the curtain of insect repellent we had drenched ourselves with. They grew in numbers, until it was difficult to see the sun through the voracious fly swarm above our heads. Frenzied buzzing horseflies became noisily trapped in our long hair and select kamikaze flies would creep between our sweaty fingers to inflict amazingly painful bites.

It was starting to look like we might become the first known case of climbers eaten by flies when suddenly all the horseflies dipped their wings, did a double roll and turned tail. They flew off down-canyon–a roaring cloud of instant misery. The reason for their retreat stood by the trail snarling evilly, shovel in hand. Even horseflies don’t mess with SMOKEY THE BEAR!! Of course, a sudden breeze might have helped too.

We had arrived at the Wilderness Boundary! There beside the plywood Smokey was an 8-foot tall, solid redwood sign proclaiming:

ENTERING SAWTOOTH WILDERNESS AREA

CHALLIS NATIONAL FOREST

PLEASE REGISTER FOR YOUR OWN

PROTECTION!We had some fun filling out the overly-detailed registration form, but then none of us wanted to put our name on it as group leader. In a moment of inspiration, I exclaimed “Let’s call ourselves the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club” and, since I thought of it, I get to be manager.

We had elections on the spot and Gordon chose to be Social Chairman, Harry Bowron, Treasurer, and Joe Fox, Member at Large. The next day we climbed Mount Regan (which was somewhat challenging) and had a great time. Our mountain fun was just starting. We never had scheduled meetings or dues but, in order to become a member, you had to go climbing with another member. Of course Gordon took his duties as Social Chairman seriously. He was soon adding females to our club. I must admit to being jealous of Gordon’s social skills in the 1970s and 1980s. His girlfriends were always attractive, assertive and intelligent. Gordon was a “babe-magnet” of the first magnitude. Thus, he was the perfect Social Chairman.

The rest is history, and we did climb Mount Regan the next day.

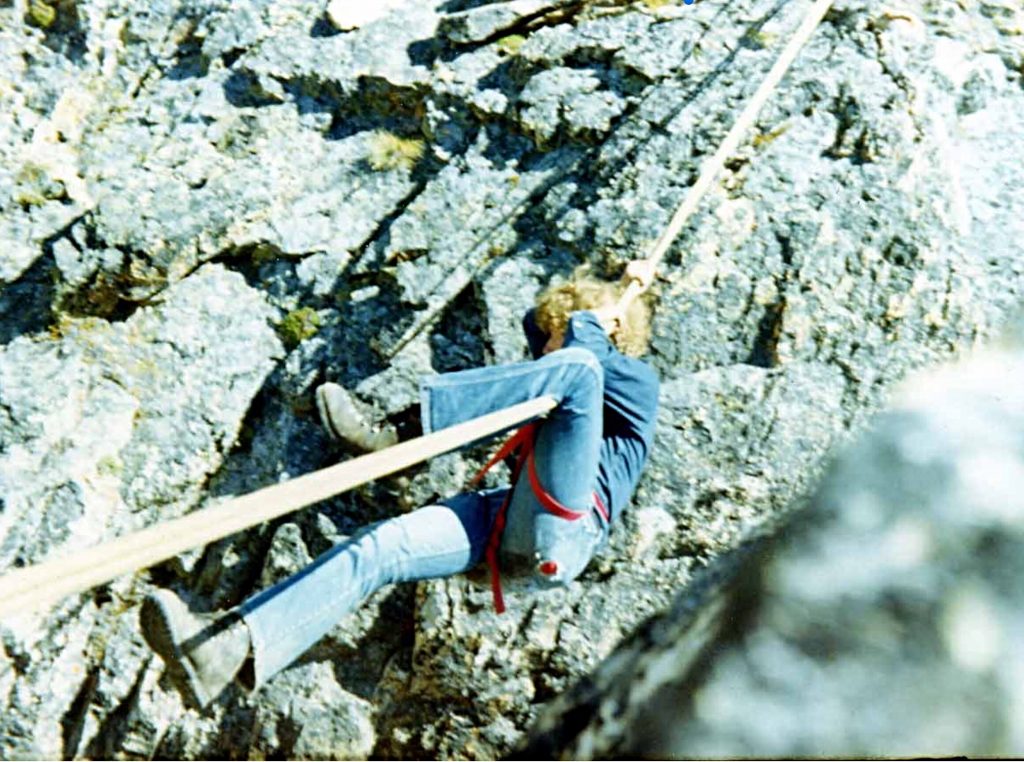

Gordon Williams on a Tyrolean Traverse near the summit of Mount Regan. Note the vintage Goldline rope. After our spur of the moment start in July 1970, we never had regularly scheduled meetings, but we enjoyed a 4th of July group outing in the Pioneer Range and another outing in 1971, with about 20 friends attending. For the most part, DFC&FC members climbed together in small groups.

A Gordon Williams photo of most of the 1970 party group. I’m at the left in the front row. In the early 1970s, Idaho mountaineering was a different world than now. It was a world without good USGS maps, climbing guidebooks, cell phones, GPS devices, an internet to access for climbing information and satellite rescue beacons. Thus, we suffered considerable obstacles to safe and sane mountaineering, but let me assure you, rock climbing and mountaineering in Idaho was a helluva lot more adventurous and a lot more fun then than it is now. Amazingly, although some of our climbing students suffered long scary slides on steep snow slopes, there are no serious climbing injuries or deaths in the history of the DFC&FC.

In keeping with the local ethics of Sawtooth climbing which sought to keep the Sawtooth Range unpublicized, club members did not (for the most part) publish their climbing exploits. Still, members made some impressive ascents and all of us were actively invested in exploring the nearby mountains.

In the early 1970s, Gordon Williams was instrumental in leading groups which pushed the limits of Winter climbing in the Sawtooth Range. There were some setbacks, but under Gordon’s leadership, there were successes. The two most notable Winter first ascents were the Finger of Fate and Mount Heyburn.

Harry Bowron and I completed several notable new routes in 1971 and 1972 in the Sawtooth Mountains, including two new routes to the summit block of Big Baron Spire and a new route on the South Side of Warbonnet. Contrary to local ethics, I did publish an account of a new route I achieved with Mike Paine and Jennifer Jones on Elephant’s Perch in 1967. My ethical breach insured that no other climbers would climb the same route and claim the glory of a first ascent on the biggest wall in the Sawtooths.

Here’s a group of us at our 4th of July 1971 gathering. Gordon is at left in the back row. Others pictured include William Michael Bird, Gordon K. Williams, Ray Brooks, Danny Bell, Vicki Smith and Randy Felts. The only tangible achievement of the DFC&FC was to restore Pioneer Cabin, which sits on a high ridge east of Sun Valley adjacent to the high peaks of the Pioneer Range, in 1972 and 1973. I was in Moscow, Idaho at the time and had nothing to do with the project. Credit for the rehabilitation goes to Gordon Williams, Robert Ketchum, Chris Puchner and others who donated materials, helicopter time and labor.

Gordon Williams was insistent on painting our club slogan: “The higher you get, the higher you get” on the roof. Somehow, that painted slogan survives on the roof of Pioneer Cabin to this day. Here’s a link to an Idaho Public TV article on it: Pioneer Cabin

Long-term club member John Platt recalls another club slogan he heard while skiing potential avalanche terrain into the Finger of Fate in 1972. “Stay High & Spaced Out.” A high-end outdoor magazine, Adventure Journal, published an article on Pioneer Cabin and the DFC&FC link in their second issue in 2018.

After a high-point with the Pioneer Cabin restoration, the DFC&FC never managed to hold more scheduled events. Nevertheless, members continued to use the name on wilderness registration forms and an informal competition to achieve the most yearly “back-offs” from major rock climbing routes or mountain peaks, persisted into this century. We of the DFC&FC enjoyed fiascos. In the era before decent USGS maps, climbing guidebooks, cell phones, GPS devices, an internet to access for climbing information and satellite rescue beacons, success on routes was not assured and failures were cherished.

In 2001, Gordon Williams hosted a 30th Anniversary party for a surprising number of DFC&FC members. I recall around 20 attendees, including one who flew in from Alaska for the occasion.

In 2012 Matt Leidecker interviewed Gordon Williams, Jacques Bordeleau and me for historical information on notable climbs DFC&FC members had achieved in the Sawtooth Mountains. Leidecker included several paragraphs recounting the club’s history in his fine hiking guide “Exploring The Sawtooths.”

Matt summed up the DFC&FC club achievements in the Sawtooths with a Gordon Williams quote: “I got to thinking what was the shining achievement of our time in the Sawtooths and I came to the conclusion that it was simply to have a good adventure. Once you learn how to do that, you can keep doing it forever.”

DFC&FC members Chris Puchner, Gordon Williams and Mark Sheehan retreating from their first Winter attempt to climb Mount Heyburn. Jacques Bordeleau Photo -

Gordon K. Williams by Ray Brooks

Editor’s Note: see additional photos assembled by Jacques Bordeleau at the following link: Gordon K. Williams Photos

My friend, high school classmate, climbing and adventure buddy Gordon Williams (aka Stein Sitzmark and, on occasion, “Imstein”) passed away on Tuesday July 23rd at age 69 and 3/4. He leaves a lot of good friends and his loving family behind.

Gordon was trained to be a registered surveyor but was also an artist by choice and inclination. Many folks enjoyed his keen wit and loquacious manner. He was interested in many, many things, but his photography has been a major achievement since the late 1960s.

I met Gordon soon after his family moved to Ketchum in the mid-1960s. Although I was a year ahead of him in high school, we were almost the same age. Like many have since, I found him interesting and likable, but we were not close friends in high school. However, I must confess to being the person who introduced him to roped rock climbing.

The Early Days

In the Summer of 1969, Jim Cockey took an afternoon to teach his younger half-brother Art Troutner and me some key elements of roped rock climbing near McCall. We learned how to belay climbers with a rope, hammer in pitons to anchor belays and rappel off a rock cliff, in a few short hours of instruction. I went home to Ketchum and ordered a climbing rope, some soft-iron pitons and aluminum carabiners from REI. I then proceeded to share my inadequate and dangerous knowledge of the rudiments of roped technical climbing with Gordon and his high school classmate, Chris Hecht. They were instant converts and soon Chris thereafter ordered better climbing gear. That Winter, we read up on climbing techniques and practiced climbing knots until we could tie them while stoned.

By the Summer of 1970, we were ready for real mountains. Gordon, Chris and I started with a bang by climbing 10,981-foot Boulder Peak near Ketchum in early June. Next, we convinced a number of friends to hike into Wildhorse Canyon in the Pioneers for the 4th of July weekend. But during that weekend, Chris, Gordon and I encountered steep and difficult rock on the North Face of 11,771-foot Old Hyndman Peak and an oncoming thunderstorm convinced us to retreat.

The Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club

For our next trip into the Pioneers, we were mentored by my “somewhat” experienced climber-friend Harry Bowron, who summered in Stanley. Harry had been exposed to roped climbing on various Sierra Club trips and had recently survived a long National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) outdoor skills course in the Wind River Range. His knowledge and abilities helped our climbing skills considerably.

It was a hot day in late July 1970, during our hike into Mount Regan above Sawtooth Lake. Pursued by evil, we hurried up the dusty trail. Our packs were heavy, each with 60-70 pounds of climbing and camping gear. It was a hot, humid and windless morning. We were sweating hard and were being chased mercilessly by a full-strength squadron of horseflies.

Flies dive-bombed us incessantly, trying to break through the curtain of insect repellent we had drenched ourselves with. They grew in numbers until it was difficult to see the sun through the voracious fly swarm above our heads. Frenzied buzzing horseflies became noisily trapped in our long hair and select kamikaze flies would creep between our sweaty fingers to inflict amazingly painful bites.

It was starting to look like we might become the first known case of climbers eaten by flies when suddenly all the horseflies dipped their wings, did a double roll and turned tail. They flew off down-canyon–a roaring cloud of instant misery. The reason for their retreat stood by the trail: snarling evilly, shovel in hand. Even horseflies don’t mess with SMOKEY THE BEAR!! Of course, a sudden breeze might have helped too.

We had arrived at the Wilderness Boundary!! There beside the plywood Smokey was an 8-foot tall, solid redwood sign proclaiming:

ENTERING SAWTOOTH WILDERNESS AREA

CHALLIS NATIONAL FOREST

PLEASE REGISTER FOR YOUR OWN

PROTECTION!We had some fun filling out the overly-detailed registration form, but then none of us wanted to put our name on it as group leader. In a moment of inspiration, I exclaimed “Let’s call ourselves the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club” and, since I thought of it, I get to be manager.

We had elections on the spot and Gordon chose to be Social Chairman, Harry Bowron, Treasurer and Joe Fox, Member at Large. The next day we climbed Mount Regan (which was somewhat challenging) and had a great time. Our mountain fun was just starting. We never had scheduled meetings or dues but, in order to become a member, you had to go climbing with another member. Of course, Gordon took his duties as Social Chairman seriously. He was soon adding females to our club. I must admit to being jealous of Gordon’s social skills in the 1970s and 1980s. His girlfriends were always attractive, assertive and intelligent. Gordon was a “babe-magnet” of the first magnitude. Thus he was the perfect Social Chairman.

In the early 1970s, Idaho mountaineering was a different world than now. It was a world without good USGS maps, climbing guidebooks, cell phones, GPS devices, an internet to access for climbing information and satellite rescue beacons. Thus, we suffered considerable obstacles to safe and sane mountaineering but, let me assure you, rock climbing and mountaineering in Idaho was a helluva lot more adventurous and a lot more fun then than it is now. Amazingly, although some of our climbing students suffered long scary slides on steep snow slopes, there are no serious climbing injuries or deaths in the history of the Decker Flat Climbing & Frisbee Club.

Gordon glissading “way too fast” on our way down from climbing the highest peak in the Sawtooths (June 1971). Gordon As A Climbing Pioneer

In the early 1970s, Gordon was active in attempting the first Winter ascents of some Sawtooth Range peaks which even difficult to climb in Summer. There were some setbacks, but he was integral in the first Winter ascent of the difficult pinnacle, The Finger of Fate, and a large peak with no easy way to the summit, Mount Heyburn.

In mid-March 1971, Gordon, his Seattle friend Roxanna Trott and I enjoyed a somewhat unconventional moonlight Winter ascent of Boulder Peak. We knew the snow was very firm with near zero avalanche danger (despite our lack of avalanche awareness training). Gordon and I departed Whiskey Jacques at 1:00AM with a drink, picked up Roxanna at her place, drove to Boulder Flat and skied into the Southwest Side of Boulder Peak on Styrofoam-hard snow under a full moon. We arrived on the summit at dawn and were back in Ketchum for a late lunch.

Here’s my photo of Gordon & a friend Roxanna Trot, on a winter moonlight ascent of 10,891’ Boulder Peak near Sun Valley. Pioneer Cabin

In 1972-1973, Gordon, Chris Puchner, Robert Ketchum and others worked on the now locally-famous restoration of Pioneer Cabin above Sun Valley. Pioneer Cabin (a 1937 Sun Valley Company high mountain ski hut) sits on a scenic ridge at the edge of the Pioneer Mountains. Here’s a link to an Idaho Public TV article on the cabin which mentions the history: Outdoor Idaho. Gordon’s hard work on Pioneer Cabin and his insistence on painting the DFC&FC slogan “The Higher You Get, The Higher You Get” on the newly-repaired roof of Pioneer Cabin made both him and our club famous in western mountain lore. The story has appeared in several outdoor magazines.

Gordon and the Finger of Fate

Gordon was active at rock-climbing and mountaineering through the 1970s. Gordon really enjoyed climbing the challenging Open Book Route on the Finger of Fate in the Sawtooths. By 1978, it was a routine climb for him and Mark Sheehan. On one of these outings in 1978, they were hit by a severe thunderstorm just below the top of the Finger. Suddenly lightning was hitting nearby peaks and it was raining hard. They could not climb the final difficult summit pitch in the rain and with their single rope, descending the Open Book Route was unthinkable. Getting off the rock was essential and they started to down climb on what seemed to be a safer alternative. As Gordon rappelled, the rope slipped . . . but I will let Gordon tell the story.

Gordon’s Close Call by Gordon K. Williams

In late July 1978, I hiked into Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains with my friends Mark and Gail Sheehan. We were off to do our favorite rock climb, the Open Book Route on The Finger of Fate. By 1978, I had climbed the classic Class 5.8 route a number of times and it had become normal for us to hike in, climb the route and return back to Ketchum on the same day.

The Finger of Fate as viewed from the Southeast. Perhaps we made a bad choice. The weather was deteriorating and we put on the climb anyway. That is how we first met Brent Bernard. When Brent and several of his friends had arrived at the base of the Open Book, we hadn’t yet finished the first pitch. They sat down to wait for us. While waiting, they looked at the sky. The sky told them to back off. They walked away. That was a good choice.

Twenty feet of steep snow guards the bottom of the climb. In early July, it is cold on the North Side. First thing in the morning, that snow is hard. We chopped steps, kicked the snow off and gingerly stepped onto the rock. You must immediately swarm up a blank section with wet boots. This may be the crux. There is no warm up. There is not much to work with. Go up or go home.

From the belay ledge, I watched Mark Sheehan levitate up the first pitch. It is the only place big enough for two and a welcome refuge after working around the foreboding overhang. Looming at the top of a perpetually cold jam crack, the clean overhang extinguishes hope. There appears to be no way around it. One must push up under that overhang then exchange heel for toe in the crack. Turning around to face out puts your head where the next move becomes visible. Exit right onto the face for a “Thank God” handhold that is nearly beyond your reach. Swinging across on one hand brings you to where it is possible to work up the face and mantel on the ledge. Some consider this the crux problem. On arrival, Mark expressed pleasure. We were having fun.

Gordon at the top of the jam-crack lead on the second pitch of the Open Book. The crack ends under the overhang and climbers are forced out right onto thin holds. Mark Sheehan Photo Our plan had been to travel light and fast. One rope, three slings and about a dozen chocks would be enough. We had everything necessary and nothing more. Heavier clouds were beginning to build. They told us to pick up the pace. Two more pitches would bring us to the top of the Book. Then send a short pitch up the ski tracks, crawl under the summit block, jump the gap and bag the summit. We would rappel from an old bolt and down climb to another short rap above the saddle. Our plans began to change half way through the third pitch.

Lichens cover most of the rock on the Finger. Lichens are composite organisms consisting of a symbiotic relationship between an alga and a fungus. The fungus surrounds the algal cells, enclosing them with complex fungal tissues unique to lichen. Lichens are capable of surviving extremely low levels of water content. When fully hydrated, the complex fungal tissues become slippery. Rehydration requires several minutes. We were still adapting to light rain and slippery rock when thunder started echoing off nearby mountains.

Suddenly our location near the top of a prominent pinnacle seemed imprudent. We were climbing a lightning rod. Mark and I are both afraid of lightening. We wanted to get down fast. From the ridge above the Book we had two choices. Knowing the South Side to be much shorter, we decided to rappel that way. Mark split the coil while I threw a sling over a horn on the ridge. No time to tie knots at the ends – throw the rope. More thunder and louder now we were in a panic to get off. Assemble four carabiners as a brake, clip into the line and ease gingerly to the edge. Wind was whipping rain from every direction. I would be careful not to slip on the wet rock or rap off the end of the rope.

Starting down with feet spread wide I was leaning back perpendicular to the wall so my boots wouldn’t slip. Descending slowly and looking down for more foot placements, I felt the line above release. Turning my head to look up, I saw the rope and anchor sling whipping against the sky above. My rappel anchor had slipped off the rock horn and I was accelerating in free-fall with hundreds of feet to the floor… a dead man falling.

Instantly I understood this to be the end. There was no hope of surviving such a fall. Anxiety and fear disappeared. Perhaps I stopped thinking. Time did not compress or elongate. There was certainly no flipping through old photos or videos of past events… no life flashing by. This was the end of the film, the part where the screen goes blank.

I have no recollection of hitting the wall. It knocked the wind out of me. I came to my senses gasping for air, unable to get the first bite. It was a raw shock, being jerked from some quiet place back into my body. Everything was confusing. I was hanging upside down pressing lightly against the rock wall. Nothing made sense. How could Mark have caught me? My hands found the rope and I struggled to get back upright. Stepping onto a toehold produced sharp flashes of pain in my left ankle. It was broken.

Mark was peering down from the ridge. Raindrops were hitting my face. The situation was coming into focus. He hadn’t caught the rope. Instead, it had snagged on the rock face. My rappel brake was jammed. This had prevented my sliding off the end of the rope after slamming into the wall. I used one hand to loosen the brake while holding onto the wall. Easing weight onto the rope again, I rappelled to a ledge fifteen feet below. Off rappel, a flick on the rope set it free from the snag… first try.

Mark was stranded on the ridge and the threat of lightening was not yet past. He had to get down. We were too far apart to throw the rope back up so Mark rummaged into his pack for cord. He lowered it… too short. Next he pulls out his boot laces and tied them onto the cord. Altogether it reached and I sent the rope up. Mark set a new anchor and rappelled to my level. We followed the ledge system around the East Side back onto the North Face trying to find the top of the PT Boat Chock Stone. We had enough gear to set two more rappel anchors and it would take five to get off the pinnacle. Several years earlier, we had left slings retreating down the Chock Stone route. In spite of their age, we hoped they might still hold our weight. They did.

Gail Sheehan was waiting at the bottom, wet and worried by our extended absence. We were greatly relieved to be off the rock. Climbing with a broken ankle was difficult, but hiking was out of the question. We had several miles of rough terrain to negotiate before getting to the lower end of Hell Roaring Lake. From there, another two miles of easy trail ran back to the car. Again Mark rummaged into his pack pulling out a Swiss army knife with a saw. He cut free some planks about an inch thick from the shell of a rotting hollow log. He then fashioned a splint that allowed me to walk by transferring some of my weight past the ankle and onto my left hand. It worked pretty well. Gail had taken all of the weight out of my pack and we three set off down the mountain. It was torture. By the time we reached the lake, I was exhausted and ready to confess. Mark offered to carry me. I said yes.

We rearranged the rope into a long mountaineer’s coil, split the coil into halves from the knot and draped it over Mark’s shoulders with the knot behind his neck. My legs ran through the coils transferring my weight onto his shoulders in a piggyback carry. Mark didn’t have to hold my weight with his arms. Gail carried our three packs. We set off down the trail. It was torture. After a few hours, Mark was exhausted and ready to confess. Gail was pretty much used up too. It was raining and the three of us were sitting on a log in the dark. We were too tired to start again. It was a low point. That is when Brent arrived.

They had waited at the cars. They knew something was wrong and were just about ready to drive out to call for help. Brent decided to walk up the trail a short way and see if he might find us. That is what he did… barefoot in the dark. We put my shoes on Brent and he carried me the rest of the way out to the road. Our self rescue had come to an end.

Life After Climbing

Around the time of the accident, he and Mark Sheehan bought an old hotel/boarding house at the onetime mining town of Triumph a few miles southeast of Sun Valley. In the early 1980s, they remodeled it into two separate two-story homes, with lots of room for possessions and the range of woodworking machinery he had acquired. Gordon’s half of that project provided him the comfortable home he had lived in since then.

Gordon knew he was lucky to have survived the accident and as a result he climbed less after that near disaster. I think flashbacks of his near death fall continued to bother him. By the 1990s he was hardly climbing at all, but Kim Jacobs talked him into climbing the Open Book on the Finger again in 2003, although she led all the pitches.

Somewhere along the way, Gordon and I adopted a toast that amused us both. We had both suffered close calls in our climbing and whitewater rafting careers and we both knew we were somewhat lucky to still be alive and healthy. Thus was born our, “Here’s to cheating death” toast at the end of every day of outdoor adventure. As some of us may have noted, “Life is so uncertain” and Gordon and I, and our friends appreciated that we had lived, for the most part, lucky and blessed lives.

In the late 1990s, Gordon started going to Nepal with small groups that were guided by his old friend Pete Patterson and Kim Jacobs. Gordon fell in love with Nepal, its people, and especially its mountains. He made 7 trips to Nepal between 1998-2008. I was lucky enough to accompany him and a small group of friends on two 16-day treks through some of the most spectacular mountains in the world.

Gordon was not doing what we considered mountain climbing but, in 2005, we did steep hiking up to a 17,500-foot summit for a spectacular view of nearby Mount Everest.

In 2010, my wife Dorita and I started doing regular multi-day climbing trips to the spectacular City of Rocks. Gordon was invited and soon joined in enthusiastically, but didn’t climb much. With the urging of our “old” friend, noted climber Jim Donini, we started sponsoring yearly camp-outs for mostly older climbers. Although Gordon seldom climbed at these meetings, he enjoyed being around other climbers and the scenic crags of the area.

At our gatherings, climbers from all over the U.S. enjoyed Gordon, his good temper, his stories, his wit, and his wisdom, as did we all. This year, including 4 nights at the City of Rock outing, my wife Dorita and I got to enjoy Gordon’s fine company on some, or all, of 10 precious days.

Here’s my 2008 photo of Gordon and a merchant of Lo Manthang in remote Mustang, Nepal. Gordon also became involved in white-water rafting in the 1980s and survived many challenging river trips, including two Grand Canyon adventures. In 2016, we finally enjoyed a multi-day river trip with him, thanks to our mutual friend Chris Puchner. We loaned Gordon our “sportscar” raft and he navigated it down the large and sometimes scary rapids of Idaho’s Main Salmon River without mishap.

Part of the fun of being around Gordon was his rich imagination. His little plastic friend Piglet traveled many places with him and proved fascinating to Gordon’s many female friends.

Here’s Gordon at the City of Rocks sharing a drink with Piglet while my wife Dorita politely averts her gaze. Although Gordon continued to work part-time, he was usually willing to go explore old mines or Native American rock art with us.

This photo of Gordon was taken this Spring as we were hiking back from a 1880s mine we explored west of Hailey. Final Thoughts

I deeply appreciate that except for a miraculous catch of Gordon’s falling rappel rope by a rock flake, during a thunderstorm on the Finger of Fate back in 1978, we almost certainly would have lost Gordon 41 years ago. So we have been in the bonus Gordon round for many, many years, which I know we are all grateful for.

So we have been blessed that Gordon survived not only that 1978 storm and rappel failure, but he also graced us with his lively presence until now.

I miss him.

-

An Overview of the Lookouts in the Salmon National Forest by Bing Young (1982)

According to A History of the Salmon National Forest, by 1916 there were two lookouts in the Salmon National Forest, at Blue Nose and Salmon City Peak (later given the name “Baldy“). It was assumed that most of the forest could be seen from these two points. Cathedral Rock, in the Bighorn Crags, was also used at times to see the Middle Fork area, and there was apparently even a telephone line at one time to Cathedral Rock. [Footnote 7: Personal conversation with Mr. Howard Castle who remembers being told about this phone line. The author seriously doubts, however, that the line was ever extended to the top of the mountain, though it may well have existed at the base of Cathedral Rock. Cathedral Rock is an extremely sheer crag-type mountain not to be climbed except by professionals, which no doubt affords a great view of the Middle Fork area and which would have been left blind by just the use of Baldy and Blue Nose.]

But the effect of the Weeks Act was to change that situation. The 1918 Forest map lists Taylor Mountain, Lake Mountain, Haystack Mountain, Blackbird, Sagebrush Mountain , and Ulysses as lookouts. Apparently Blue Nose was also still used.

The Blue Nose Lookout is unlocked and is in need of some serious repair work. At this point, there were few lookout buildings as we know them today. As late as 1924, lookout structures had been built only on Long Tom, Baldy, Taylor, Stein, and Blackbird Mountain. Most of the lookout “houses” built at that time were extremely small—most 9‘ x 9’—and in 1924, only Blackbird Mountain had the more typical 14′ x 14′ structure of today’s lookouts.

Rather than live in lookout buildings, most lookouts were camped near mountain peaks during the critical fire period. Many of those lookouts were also “smokechasers,” that is after finding a fire, the lookouts would take off to put it out. This was particularly the use before telephone lines were installed. Lookouts were thus placed in many locations in the forest, often varying from year to year. Since no visibility maps (those indicating the area seen from a lookout) were then available, lookout stationing was not planned in a very organized manner.

It was decided about this time that some lookouts should be considered “primary” and manned for the entire fire season at all times; “secondary”, which would be manned only for a month in the worst part of the fire season ; and “tertiary” or third line lookouts, manned only in bad fire years. In 1923, the Salmon National Forest’s primary lookouts were Taylor Mountain, Blackbird, Blue Nose, and Long Tom. Secondary lookouts were Middle Fork Peak, Two Point, and Granite Peak. Additional smokechasers were stationed at various paces in the forest, including Lake Mountain, Sagebrush, Haystack, and Sheepeater Point. Lookout selection was not made with a lot of information and choices varied from year to year.

In 1926, the first visibility maps were made of many peaks of the forest. Henry Shank, in an effort to better select the primary and secondary lookouts, tried to plot the area visible from each lookout station. The 1926 map indicates Lake Mountain, Stein, Haystack, Sheepeater, Two Point Peak, and Sagebrush as primary lookouts. I assume that Taylor Mountain and Blue Nose were also still in use, as they appear on later maps.

By 1929, 19 points in the forest had either a lookout or a dual/smokechaser. The year 1929 was one of the worst fire years in the recorded history of the Salmon National Forest, particularly with the Wilson Creek Fire. In order to avoid large conflagrations of the size of the Wilson Creek Fire, the early detection system needed additional improvement. This determination to improve detection, coupled with the surfeit of workers made available by the Great Depression, enabled the Forest to initiate a massive lookout construction program. By 1932, 23 lookout points were in operation in the Salmon National Forest, with selection and construction contemplated for 7 more. Smokechasers were also stationed at the Indianola, Hughes Creek, and Yellowjacket Guard Stations.

1935 appears to have marked the time when lookouts reached their peak. Thirty-four lookouts then stood as sentinels over the forest. Buildings had been set up on nearly all of the sites, even though many weren’t primary lookouts. All seemed to be hooked up to telephones.

Just when the lookouts began their decline is not clear, but it is known that by the early 1940s some were being abandoned—particularly early ones like Duck Creek Point and Taylor Mountain. Perhaps this was partly due to the war—there weren’t enough men around to staff all of the lookouts. This is when women began to serve as lookouts. Money was short and it was recognized that there was much visibility duplication in the lookouts.

The remains of the Taylor Mountain Lookout. Even without the war, the decline of the lookout system was inevitable. As early as the 1920s, Region I (Missoula, Montana) had been experimenting with the airplane as a fire detection tool. If anything, the war probably delayed the demise of the lookout system, as airplanes, pilots, and the like were needed more in the war that they were in experimenting with forest fire detection.

After World War II and the Korean conflict, aerial detection began to change the scene. Smokechasers became smokejumpers—at least in the more remote areas—and airplane “watchdogs” replaced many lookouts. Most lookouts faded out gradually one or two at a time until in 1982 there were only 6 of the original number remaining: Long Tom, Stormy Peak, Sagebrush, Stein Mountain, Middle Fork Peak and Sheephorn. Butts Point was not manned in the 1982 season, but the North Fork Ranger District has not given it up, as it is still considered to be of primary importance. Fire management personnel have indicated that it is unlikely that any of the others will be used again.

Middle Fork Peak as viewed from Peak 9101. An interesting trend in the site selection of lookouts was the preference to use the highest peaks in the Forest. Pre-1930 lookouts included Taylor Mountain, Blackbird, Lake Mountain, Cottonwood Butte, Duck Creek Point, Two Point Peak and Middle Fork Peak—all over 9,000 feet. Post-1930 lookouts included Granite Mountain, Jureano, Sheephorn, Hot Springs and Butts Point. Nearly all of the post-1930 lookouts are under 8,500 feet and most are less than 8,000 feet.

This change in trend was probably because the high lookouts may cover great distances, yet they are often too high for visibility of the high-hazard country of lower elevations right under them. Indeed, most of the high lookouts have no view of large or important drainage bottoms. The Forest is hampered by the problem of its extreme verticality. Canyons are generally narrow, steep and very deep. This has made it difficult to use the “highest peaks” as lookouts as is done by many other Forests.

In the early 1930s, forests were required to have 80 percent lookout coverage of the Forest’s high fire-hazard acreage. The only way to see much in the rugged Salmon River country was to “come down” in elevation. Thus, later lookouts like Granite Mountain and Sheephorn don’t have the horizontal viewing distance that some of the older lookouts do, like Blue Nose and Taylor Mountain. They do, though, afford excellent views of specialized high-hazard drainages.

Other problems encountered by the high peaks were: the great distances to water which lookouts had to hike to daily; great distances to “climb down” to a fire; the problem that high lookouts were often “fogged in” in the morning (one of the best times to find fires); and rugged and costly to packers supplying the high lookouts.

Today’s lookouts have been selected by the Forest Service through a long process of elimination. They have excellent views of high-hazard drainages and nearly all report fires every year.